Written by Spencer Pearce and Jacquelyn Deppe

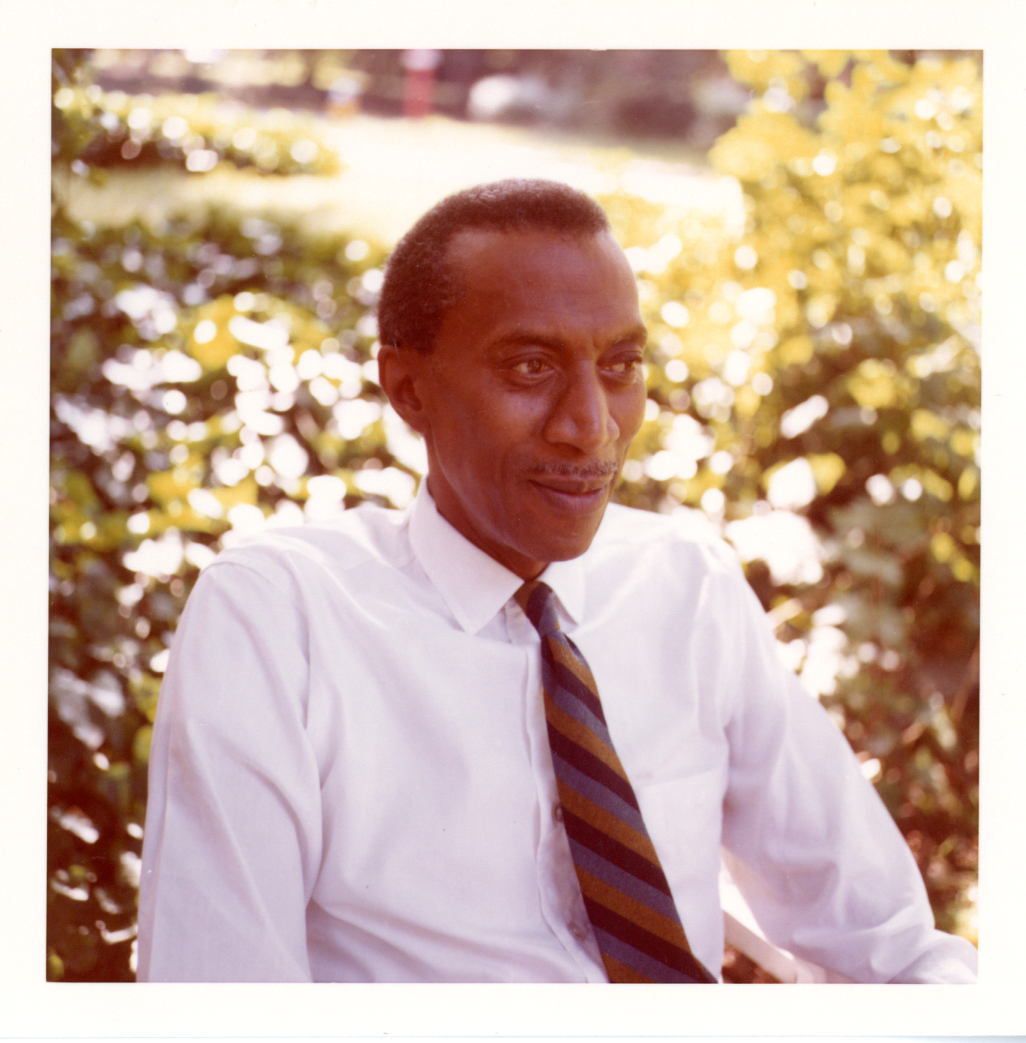

Dr. Francis Monroe Hammond (1911-1978) was Seton Hall University’s first African-American professor who was “committed to racial equality, grounded in a Catholic understanding of human dignity, was the defining fact of his life.”1 He was born in Liverpool, Nova Scotia, Canada on November 24, 1911, later moving to Pleasantville, New Jersey where he would attend grammar school and high school and later become a naturalized U.S. citizen.

Fluent in French, Dr. Hammond would briefly attend Howard University and New York University before he left to attend the University of Louvain in Belgium. He earned two certificates from the University of Louvain in Belgium and the University of Haiti in 1934 and 1935 respectively. Dr. Hammond then went to Xavier University in Louisiana, sister school of the University of Louvain. There he would become a teaching fellow and meet his wife, Violet Hayes, who also earned a degree from the school. After Dr. Hammond obtained his BS in chemistry and biology in 1937, the couple would later go on to have ten children together.

Dr. Hammond returned to the University of Louvain from 1938 to 1939 where he would earn a Licentiate in Philosophy. Dr. Hammond went back to Louisiana to start his teaching career as an assistant professor of philosophy from 1940 to 1945, also gaining a PhD in Philosophy and Social Psychology from University of Laval in his birth country of Canada in 1943. He would then be made chairman of the Modern Languages Department of Southern University in Louisiana from 1945 to 1946, aided by his ability to speak seven languages including Spanish, Italian, Portuguese, Dutch and German.

Dr. Hammond returned to the University of Louvain from 1938 to 1939 where he would earn a Licentiate in Philosophy. Dr. Hammond went back to Louisiana to start his teaching career as an assistant professor of philosophy from 1940 to 1945, also gaining a PhD in Philosophy and Social Psychology from University of Laval in his birth country of Canada in 1943. He would then be made chairman of the Modern Languages Department of Southern University in Louisiana from 1945 to 1946, aided by his ability to speak seven languages including Spanish, Italian, Portuguese, Dutch and German.

Hired under Monsignor James F. Kelley, Dr. Hammond came from Southern University in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. He became a Professor of Philosophy who would rise to head the Department of Philosophy, the oldest department in Seton Hall history, in 1946 October where he supervised a staff of fourteen teachers and four priests. The Philosophy program only allowed students “who have shown signs of intellectual ability, judgment, and studious habits in their Freshman and Sophomore years are admitted.”3

In 1949 Dr. Hammond organized and moderated the Philosophy Circle which was a club to help broaden students’ knowledge in philosophy and to stimulate further interest in it ’49 248. Philosophy Circle consisted of:

“a student committee prepar[ing] programs for members. Reading of the works of important philosophers, both past and present, is encouraged to enliven group discussions which furnish the nucleus of the circle’s activities. Last year, Dr. Charles DeKonnick, Dean of the Philosophy Faculty of Laval University, delivered a splendid lecture on “Dialectical and Historical Materialism.”3

The 1949 Galleon yearbook stated:

“Dr. Hammond is amazed by the amount of student enthusiasm in the philosophy club. “Before the war,” he recalls “students were indifferent, generally, toward philosophy. Now there is a new awareness — perhaps because the students are older and more mature, maybe because of their experience with foreign peoples and ideas while in service.”

To Dr. Hammond, philosophy is basically the study of a way of life. “And,” he asserts, “we hope, in the Philosophy Circle, by reading, judging and comparing various ideas, to arrive at a firmer grasp of the Christian way.”3

Dr. Hammond was also involved in the Inter-Racial Conference (Council) at Seton Hall University which was:

“designed to inculcate in its members, and through them, in the entire student body, the traditional Catholic principles of the “oneness” of mankind, and of the dignity of the individual, irrespective of race. It strives to promote better relations among races, and to give practical application to the principles in the field of every-day living. Monthly meeting are held, both for student discussion, and far addresses by leading authorities in the field.”2

He remained at Seton Hall University from 1946-1955, leaving for a short time to become the Assistant Director of the Commission on Religious Organizations for the National Conference of Christians and Jews (NCCJ) from 1951 to 1952. Dr. Hammond returned to Seton Hall as chairman of the Department of Psychology from 1952 to 1955 before leaving the university to work with the United State Information Agency (USIA) in Europe and Africa.

Dr. Hammond went on a two-month tour Europe and Africa on behalf of the State Department before becoming employed by the USIA, where he stated that “colored diplomats are welcome anywhere in the world.” During this tour, Dr. Hammond met with the emperor of Ethiopia, Haile Selassie I, where it is believed he received the Lion of Judah medal.

He started as a Social Psychologist and Advisor on Minority Affairs in 1955, but later went on to become a cultural attaché at the American Embassy in Morocco from 1956 to 1961 where he would be a diplomat for the United States during the Cold War. During this time, Dr. Hammond and his family were profiled in Ebony magazine, where he stated that he believed his large family helped him to make friends in North Africa. Dr. Hammond and his family left Morocco for Washington D.C. in 1965, later becoming the Regional Representative for the Department of Health, Education and Welfare in 1966.

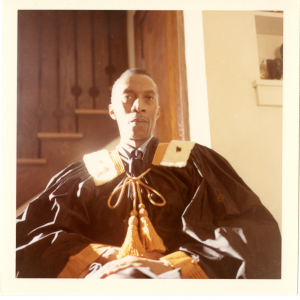

Throughout his life Dr. Hammond often commented on and published articles on race in a Catholic and global context. He was the director of the Catholic Scholarship for Negroes, and an active member of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), the Urban League and the Civil Rights Commission of Orange, New Jersey. In 1951, he would be awarded the tenth annual James J. Hoey Award for Interracial Justice by the New York Catholic Interracial Council for his work promoting Catholic education for Black people. And 1975 an honorary degree in engineering from the Stevens Institute of Technology.

His collection contains mainly correspondence in both French and English from his life and travels as well as family photographs, his degrees and awards, and even select copies of books from his library.

For more information about the collection, check out the Finding Aid.

References

- Quinn, D., & Project Muse. (2023). Seton Hall University : A History, 1856-2006. Rutgers University Press.

- Seton Hall University Bulletin of Information, 1950-1951, Box: 5, Folder: 73. Office of the Registrar records, SHU-0024. The Monsignor Field Archives & Special Collection Center.

- Seton Hall University, “Galleon 1949” (1949). Seton Hall University Yearbooks. 57.

https://scholarship.shu.edu/yearbooks/57