On November 20, 2019, Dr. Jennifer Delfino gave a guest lecture entitled “African American Language (AAL), Education and Social Justice.” Students studying Introduction to Linguistic Anthropology posed questions to her to which she responded:

On November 20, 2019, Dr. Jennifer Delfino gave a guest lecture entitled “African American Language (AAL), Education and Social Justice.” Students studying Introduction to Linguistic Anthropology posed questions to her to which she responded:

Ryan K.: Out of all the different topics in Linguistic Anthropology, why did you focus on AAL?

I was always a fan of hip hop growing up but started to pay attention to the lyrics in college. I wanted to study the cultural meaning behind the style, so wrote my undergraduate thesis on hip hop and then gradually built my research agenda around other issues related to AAL. At this point, I’m interested in what AAL tells us about language and racialization.

Jared A.: My previous question [during your lecture] asked if you think kids who speak African American Language code switch or change the way they talk entirely based on outsiders trying to talk to them. You mentioned you left the tape recorders in rooms to hear this natural dialogue. Are there any other methods you used to gather reliable data? Or were the kids open-minded and willing to talk?

My ethnographic methods included participant-observation, informal interviews, and focus groups. I collected data using the audio-recorder and taking field notes. I had known the students for a few years, so they were open with me and pretty excited about the research, even though they were a bit shy at first with the tape recorder J

Majeda M.: How does using AAL affect/change the treatment of non-black people when they use it? Are they also treated differently?

Generally, there’s a difference when whites use AAL versus when people who are not Black but racialized as “people of color” do. It depends on what you mean – treated by whom? AAL speakers are more likely to perceive other POC using AAL as “sharing” and whites using it as cultural appropriation. Whites usually produce some AAL (i.e., slang) and look cool while avoiding linguistic stigma while non-white people are pathologized for speaking it. Also, whites tend not to learn AAL as deeply as POC who share the language in common (i.e., Blacks and Latinos who live in the same NY neighborhood).

Deborah O.: During the lecture, you mentioned racial labels, but I also heard you mention racial indexes. Would they be considered to be the same thing?

Racial labels are explicit racial terms (Black, White), and racial indexes are linguistic forms or practices that are perceived as ones that are habitually taken up by a racialized group (i.e., “aks” for “ask”). Racial indexes are therefore forms that indirectly “point to” racial identity (like an index finger).

Samantha V.: When was this disctinction between AAS & “regular English” made? Because this has been an issue for centuries of African Americans being looked down upon & looked at as illiterate. If only this distinction was founded earlier certain circumstances would have been avoided.

The study of AAL came about in the 1960s when school desegregation ended. Before people started wondering if children’s “reading failure” in school had to do with language, there was no interest in studying AAL L

Daniela A.: Is it possible that there is a Hispanic-American language? I found it so interesting learning about AAL but am Hispanic and people tell me I have an accent but I was born and raised here so sometimes I get confused. Maybe AAL is being highly translated to the Hispanic community? I did grow up in an urban community, but I do not fully speak AAL.

There are definitely Spanglish and Spanish-English bilingual practices that influence phonology, lexicon, and syntax! Check out the work of Ana Celia Zentella or Carmen Fought.

Sarah R.: What in your opinion is the reason why the language itself is devolving? By that I am referring to your example of a 70, 40 & 20 year olds.

The language is not devolving, but diverging. Labov would say that is due to the racialized poverty and isolation experienced by African American communities, but another explanation is that African Americans use language to construct a culturally distinct identity, as is usually the case when languages diverge/split.

Zachary P.: How do you feel we can improve in making African American Language more respected and not have people who use it looked down upon or seen as lesser?

For several decades now, linguists have been trying to be really involved in changing public perceptions of AAL through research and dissemination, also working directly with schools to develop language programs and curricula. They have worked somewhat, and hopefully we can continue to do this kind of work. I also think it’s important to work closely with speakers to learn what they know and value about the language and build from there.

Markela Q.: Why isn’t AAL a dialect? If it’s pretty much just English? Why isn’t it called African American English?

AAE is used to refer to the distinctive forms at the level of phonology, morphology, syntax, and semantics. AAL more broadly encompasses styles of speech, such as verbal art. A lot of descriptive linguists avoid the term “dialect” in favor of “variety” to lend stigmatized languages legitimacy.

Shania L.: In terms of African American Language, do you think the judgement of this particular language (AAL) is worst (more criticized) than other “non-popular” languages?

“Non-standard”? Hard to say what’s worse or not, but perceptions of the AAL as deviant, disorderly, uneducated, etc. reflect on the racialization of African Americans whereas say, stereotypes of a white Southern accent are not that, but still depicted negatively.

Marcela V.: Growing up did you see that there was discrimination against AAL? How did you become interested in this topic and specifically concentrating on African American Studies and Gender Studies? How or why is it important to differentiate linguistic patterns between gender? Is it still relevant?

I gradually became interested in both topics over time, but it was really my linguistic anthropology and anthropology of sex and gender courses in college that got me interested. Absolutely, the study of gender and language is super important. But anthropologists tend to look at how gender is “made” in language rather than look at linguistic differences between gender(s). Taking a gender-fluid/inclusive approach is also important.

Catherine H.: How does discourse style relate to AAL?

Discourse styles are simply styles of speaking – preaching, testifying, signifying, roasting.. these are all performance-based styles associated with AAL.

Matthew W.: Were there dedicated studies focusing on AAL prior to desegregation during the 1960s and are these studies considered credible foundations of the subsect or pseudoscientific falsehoods that were common with contemporary racial views?

There was no descriptive linguistic work on AAL prior to desegregation in the 1960s.

Nicholas Z.: Would paying homage to the original creators of the language would just be not to use it? Let the creators use and don’t make it popular? Or only the people who learn the full language?

I think it’s important to consider whether people are really “learning” AAL or if there just using bits and pieces of it to sound cool without fully participating in the culture or even acknowledging that it can be a stigma for African Americans to use it. I think there’s a question I answered about “sharing” among young people of color versus linguistic appropriation, which amounts to theft. Really, it’s up to the speakers to determine what appropriate uses of the language is, cross-ethnically.

Olivia R.: Dr. Delfino, how do you forsee this issue being eradicated in the United States? What benefit would more linguistic anthropologists in government and in school systems have on this issue?

I have to be honest, “race” will be really difficult to eradicate from our history and thinking. In order to tackle the language issue, you have to change the racial order it is caught up in. Scholars are still seeking ways to have an impact, and it definitely goes beyond publishing academic work!

Olivia Z.: You talked about how white culture takes a lot of vocabulary from AAL. Is there a specific area of study that focuses on the “slang” taken from the LGBTQ community? (I see this idea a lot on social media, so I’m interested to see if there’s any research behind it).

There’s definitely research on Gay Men’s English (William Leap) and Gaybonics (Mollie V. Blackburn). You may also want to look at Rob Podesva’s work, or Lal Zimman.

Emily H.: What is raciolinguistics and how does it contribute to the social justice issues surroungind African American Language?

It’s the interdisciplinary study of race and language, drawing from sociolinguistics and linguistic anthropology.

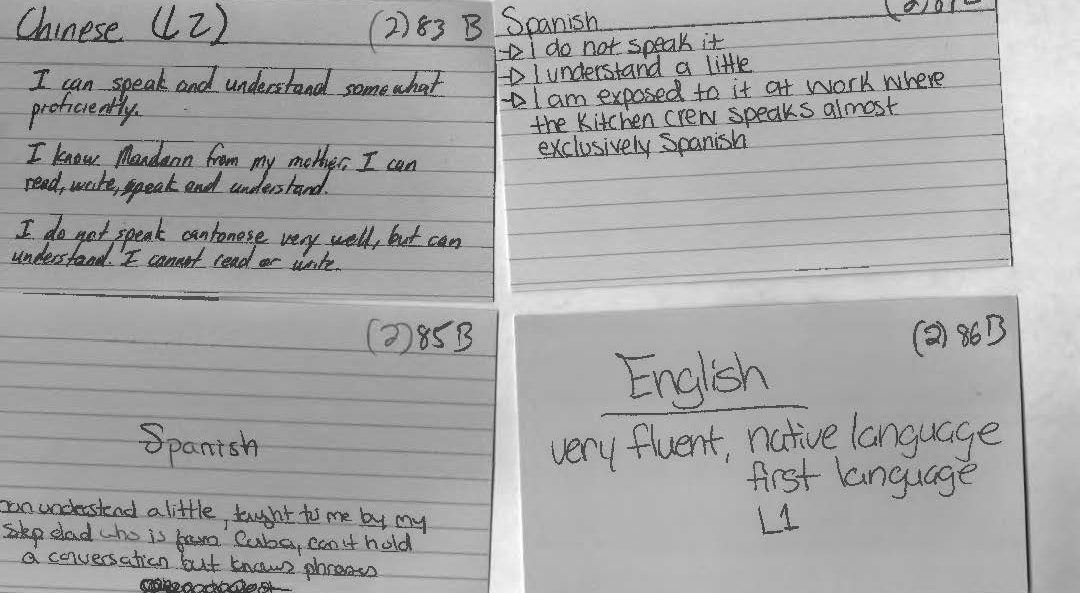

Khilna K.: So are there dialect features for everyone that speaks a second language at home or grew up around family and friends that spoke other languages around them?

Absolutely! Bilingual and Multilingual speakers have really cool practices related to code-switching, code-mixing, and translanguaging. Check out Garcia and Wei on translanguaging.

Stephanie R.: Would ebonics be described as a language, a dialect or an attribute of African American Language?

Ebonics is a different theoretical position that states AAL is West African grammar spoken using English sounds.

Claudio B.: Based on the small amount of studies conducted on female African American Language, what notable distinctions can be identified?

Check out M.H. Goodwin (“He-said-she-said”) and M. Morgan (Language, Discourse, and Power in African American Culture). They both have great answers to that, mostly focusing on conversational styles such as “signifying” and “instigating.” Really sensitive treatment on how African American women talk and why.