by Matthew Minor

Under the dome of Walsh Library hangs a quote from St. John Paul: “Faith and reason are the two wings on which the human spirit rises to the contemplation of truth.” For 25 years, Walsh Library has stood as the cornerstone of Seton Hall’s pursuit of reason within our Catholic values.

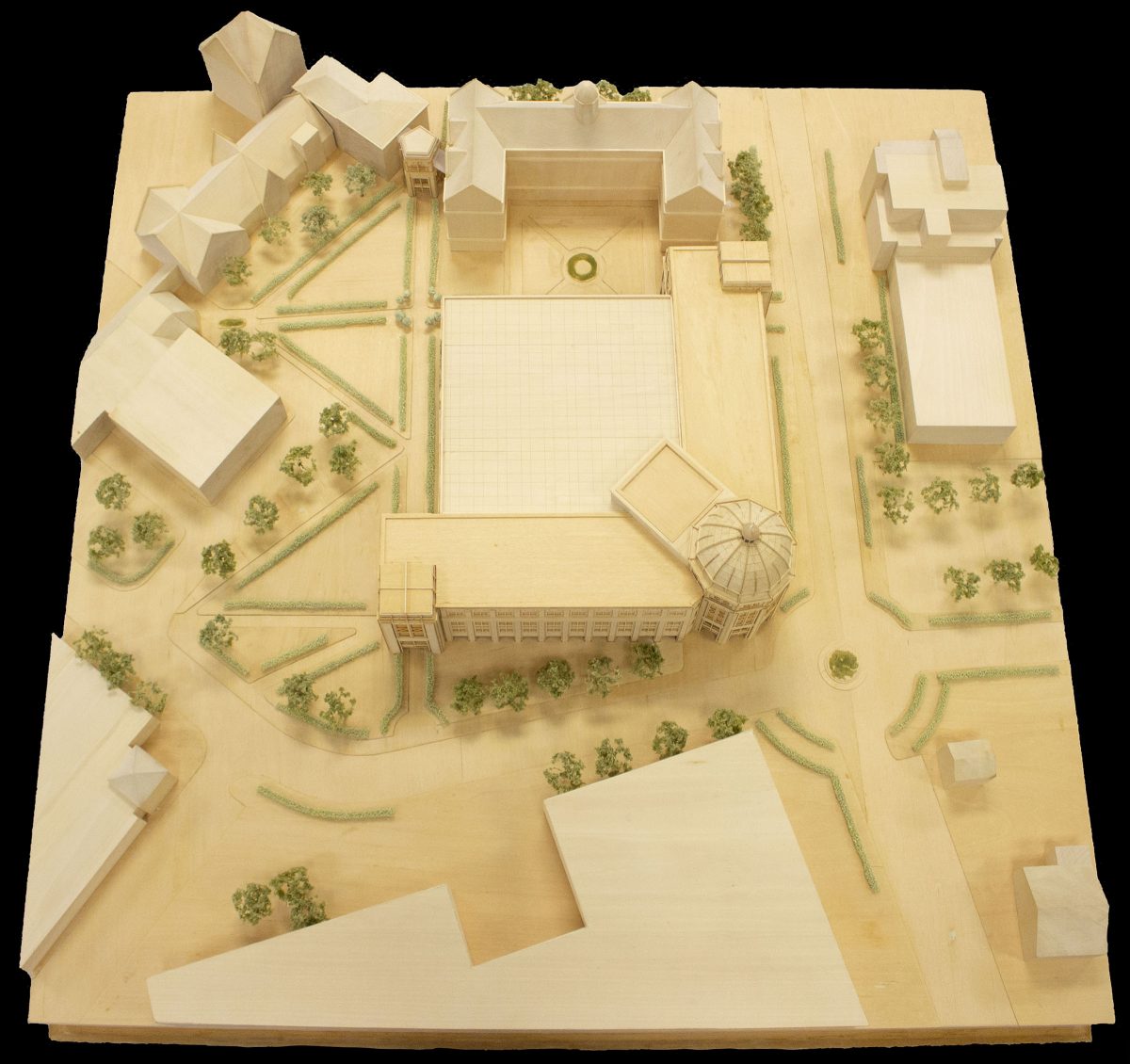

In 1990, the University’s leadership noted the need for a new library. The Very Reverend Thomas Peterson, O.P., former university chancellor, said, “Seton Hall needs a new library and she needs it now. It must be her star, the jewel of her campus.”

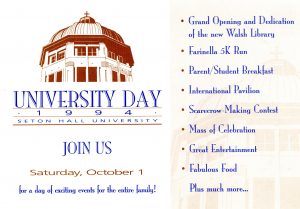

Four years later, Walsh Library opened. In the April 28, 1994 edition of the University’s student-run newspaper, The Setonian, then-Dean of Libraries Robert Jones called the library dome “‘the outstanding architectural feature of the building.’ [Jones] said the dome is the library’s crowning feature and compared it to the dome of the Library of Congress.”

In 25 years, the library has seen much change. Richard Stern, acting dean of University Libraries from 2002-2004, said, “a jewel never changes. But as humans learn, they change the buildings they inhabit to suit their needs.” And so Walsh Library has changed from a place of quiet study to a place of lively academic discussion and socialization. In 2012, Dunkin’ opened on the library’s second floor. In March 2019, an after-hours study space opened for students’ use 24 hours a day, seven days a week.

Daniela Gloor, BA ’14/MPA ’15, and her classmates in the University Honors took advantage of the library to blend their studies with this “lively academic discussion and socialization.” Walsh Library “was a place where you bonded with one another while studying, completing assignments, or writing your papers,” Gloor said. “My Honors Program classmates and I anxiously sought to study in the Library Rotunda when it was available, which has a picture-perfect view of campus and is one of the most unique places at Seton Hall. While we likely cannot remember all the works we read and studied, I can certainly recall the environment of the library, many of the memories made there, and the sleepless nights we spent working toward graduation.”

Seton Hall’s community continues to seek out the Library’s resources. In 2019, 66,000 items were borrowed, loaned and/or used, more than 44,000 books were circulated, 20,000 interlibrary loan transactions were fulfilled for books and articles and keys for the group study rooms were used more than 13,000 times.

Walsh Library has been a witness to the digital revolution that redefined research and study. Former Acting Dean Stern said the library “has grown from an institution where researchers came to find materials to an institution where researchers increasingly conduct all stages of their research in the digital sphere.”

Elizabeth Leonard, assistant dean of information technologies and collection services, said, “When Walsh Library opened in 1994, library technology, like all technology, was in its infancy…we did (yes, really) hand stamp all books going out on loan to patrons.” When the library opened, The Setonian wrote study rooms were “equipped with windows and outlets [which] are designed so students can bring their own computers and plug them into the University system.” Now, wireless laptops and a plethora of new Macs and PCs allow students to study wherever they like.

25 years later, technology touches almost every aspect of the library. In 2019 alone, roughly 427,000 full-text articles were downloaded, users viewed subject guides more than 64,000 times, the library website received 400,000 views and 1.4 million theses and dissertations were downloaded from the library’s collection. The library’s institutional repository, an online database comprising scholarly pieces such as dissertations and theses written by Seton Hall students and faculty, surpassed three million downloads in June 2019. Thanks to technology, Leonard said the library’s “resources are available to authorized users anywhere in the world, whenever they need them. We digitize lectures, books and other materials for virtual use.”

Walsh Library is looking toward the next 25 years of service to the University community. Leonard said, “We are looking forward by preserving born digital materials in a repository that will ensure they are accessible to future generations of librarians and researchers.”

View the library’s online exhibit, Walsh Libraries: 25 Years of Learning.