Have you ever imagined living in another time and place? Finding out more about daily routines in the course of recorded history through the words of historians who chronicle the story of human experience are invaluable to the present day reader. Another useful aid is a publication(s) from the actual time period which documents the doings of a person, place, or object first hand. With this in mind, and more specifically, materials that allow for personal reference from an annual perspective such as directories, yearbooks, and most notably almanacs provide the researcher with useful data to learn from by word and number alike.

An “almanac” (or “almanack” or “almanach” as they are sometimes referred to) by definition is an annual publication that provides weather forecasts, tide rates, astronomical data, and other relevant information in tabular form. Modern day almanacs have evolved to include various statistical and descriptive information such as economics, government, religion, and political results among other subject areas that touch not only upon local communities, but national and world issues in brief line item and/or summary form. The earliest known almanac published in the “modern sense” was the Almanac of Azarqueil written in 1088 by Abū Ishāq Ibrāhīm, al-Zarqālī in Toledo, al-Andalus. There have been several subsequent examples from here as found in different countries, languages, and specializations.

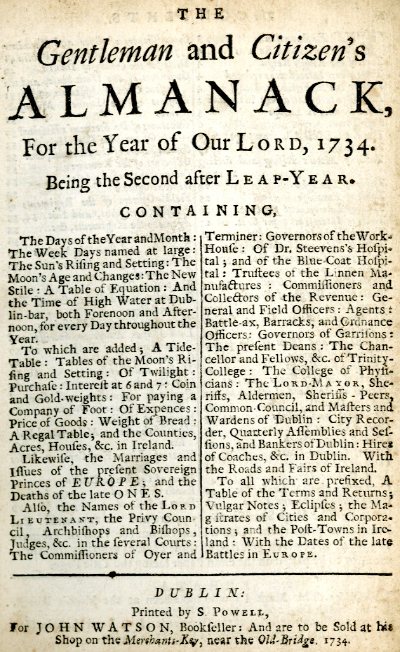

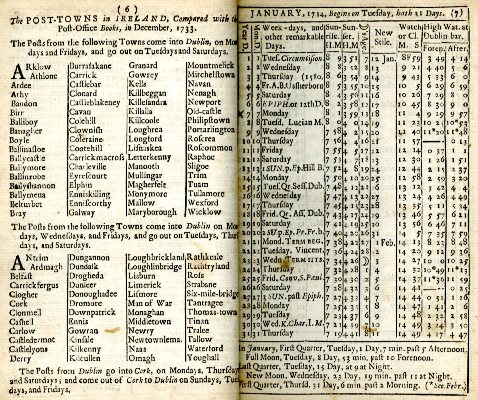

One example of an international almanac found in our collection can be located in our rare book collection if you look back 280 years ago at a far different world than the one of today. This volume entitled: The Gentleman and Citizen’s Almanack, For the Year of Our Lord (Dublin: S. Powell, for John Watson, Bookseller to be sold at his shop on Merchants Key, near the Old Bridge, 1734) is a tome that provides a look at 18th century life in Ireland. This book provides a traditional format with the following array of categories found in the index: “Tide Table, Table of Twilight,” “Table of Coin and Gold Weights,” “Table for a Company Foot,” “Table of the Price of Goods,” “Table fo the Weight of Bread,” “Masters and Wardens Quarterly Assemblies,” “Roads of Ireland,” “Fairs of Ireland,” and others. The attached illustrations provide further details on how the consumers of that day and contemporary readers can relate alike can relate to the facts and figures found here including postal service and its value for communication links before cell phones and twitter for example.

This particular publication provides an every day look at life in an Ireland that goes beyond the essay alone. This and other Irish “almanacks” from 1732-1838 and other books on the Irish experience both reference and beyond can be found here in the Monsignor William Noé Field Archives & Special Collections Center.

For more information contact Alan Delozier, University Archivist at: Alan.Delozier@shu.edu, or (973) 275-2378.