The Flatiron Building, previously known as the Fuller Building, is a skyscraper and national landmark with a storied history. Located at 175 Fifth Avenue, the 22-story skyscraper sits in Midtown, on the triangular corner of Fifth Avenue and Broadway, and sits directly adjacent to Madison Square and Madison Square Park. The building is one of New York City’s oldest skyscrapers—construction began in 1901 and was completed in 1902—at which time it was known as the Fuller Building. It was named in honor of George A. Fuller, the founder of the Fuller Company, the company that constructed the building with the intention of it serving as the company’s new headquarters. Though having passed two years before the building’s construction, Fuller is remembered by many as the “father of the skyscraper” for the legacy of his company’s achievement.1 It was also one of the city’s tallest buildings at the time of its completion at only twenty-two stories, as other taller skyscrapers such as the Chrysler Building and the Empire State Building would not be built for nearly three decades—completed in 1929 and 1930 respectively. The Fuller Building was later renamed in 1930 after CEO of the Fuller Company Harry S. Black decided to sell the building and the locals’ colloquial nickname “Flatiron,” after the building’s triangular shape resembling a household clothing iron, became more frequently used. The public’s initial reaction to the building was surprisingly mixed, with its fair share of critics. Some critiqued the number of windows the building had, others more harshly comment that they believed the building’s design was fundamentally flawed and that it would eventually lead to its collapse.2 Perception of the building changed with time, however, with the district it resides in eventually being renamed the “Flatiron District” after the building. Its construction furthermore symbolized the beginning of both the industrial age in the city and attempts made to beautify the city. Additionally, the building achieved landmark status twice; it was initially designated as a New York City landmark in 1966, and later as National Historic Landmark in 1979. Though its early reception was not a critical success, as time passed it was recognized as a truly beautiful building and received a lot of positive attention from both critics and the public alike, starting the building down its proverbial path to becoming one of the most iconic landmarks of New York City.

Construction of the Flatiron Building began shortly after the land was purchased from the Newhouse family in 1901, but use of the lot did not begin with the Flatiron. Alice Alexiou, in her historical book The Flatiron: The New York Landmark and the Incomparable City That Arose with It describes the history of the Flatiron in detail, including what existed where it now stands before it was built. Alexiou explains that the lot first housed a hotel known as the St. Germain Hotel between 1853 and 1854. It was eventually torn down after real estate investor Amos Eno bought the property in 1857, tore down the hotel, and constructed a seven-story apartment building and four three-story buildings intended for commercial use as can be seen in Figure 1.3 Under Eno’s ownership, he rented out the side of his apartment building—the Cumberland—to retailers as an advertising space. He eventually installed a canvas screen on the wall and projections of news bulletins by the New York Times and the New York Tribune were made using a magic lantern, a predecessor to the modern-day video projector. After Eno’s passing in 1899, the property was put up for sale. There were many prospective buyers, with the New York State Assembly even appropriating $3 million in funds to purchase it, but it was later revealed that Tammany Hall leader Richard Croker was using this purchase attempt as a part of a graft scheme. The property was eventually sold to Eno’s son William Eno at auction for $690,000, who promptly resold the property to Samuel and Mott Newhouse three weeks later for $801,000.4 After purchasing the property from the Newhouse family in 1901 for $2 million, the Fuller Company worked in conjunction with architect Daniel Burnham to design and construct the building. Burnham was well known for his designs for a multitude of commercial buildings in Chicago and would go on to work as a city planner in American cities like Chicago and Washington D.C. and in major cities in the Philippines such as Baguio and Manila.5 However, despite his proven track record, Burnham’s building received mixed feedback from critics. As stated previously, though many people enjoyed the daring design of the Flatiron Building, others believed it would lead to the building’s collapse. Many went as far as to label the building as “Burnham’s Folly,” furthering this implication. Additionally, the triangular shape of the building came under fire when newspaper tabloids began to center articles on conjecture-based accusations that the building was creating wind-tunnel effects due to its position next to two large streets, with numerous critics blaming the building’s design for the death of a bicyclist who was blown into the street by the wind and killed by a car in 1903.6 Regardless of the criticism that the Flatiron Building initially received, as time passed many of those who initially critiqued the building for its shortcomings eventually came to appreciate it as an architectural treasure.

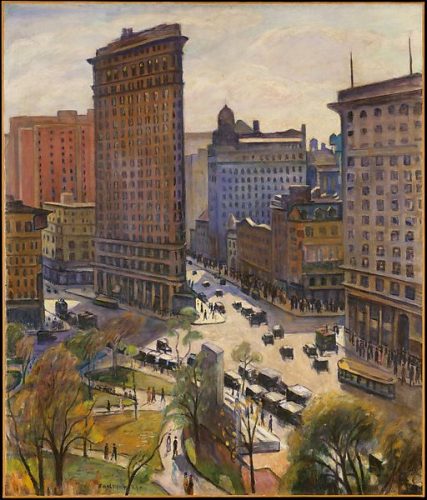

As explained by Edmund Gillon and Henry Reed in their guidebook Beaux-Arts Architecture in New York: A Photographic Guide, Burnham designed the building in a Beaux-Arts style. This architectural style was commonly used in America between 1880 to 1920 but was popularized much earlier in France, following the French Revolution in 1793. Though it utilized a French style of architecture that had become popular in America at the time, the Flatiron Building differed from many of the other early skyscrapers built in New York City before it in many ways. Firstly, as seen in Figure 2, it was the pioneering skyscraper in New York City built using the Beaux-Arts style.7 Previous to its construction, this style had been primarily reserved for use on shorter buildings. In addition, the Flatiron Building was one of the first skyscrapers to take advantage of the changing fire codes in New York City as it utilized a steel skeleton to allow for a taller and more structurally sturdy structure, an aspect of the building that can actually be seen from the outside; this is one of the Flatiron’s many unique attributes that has contributed to the building’s popularity. Furthermore, the vertical Renaissance palazzo did not share the same form as its fellow skyscrapers. While many taller buildings had a larger, blockier base with the building gradually narrowing as it rose—obvious examples of this style are the Empire State Building, the Chrysler Building, and the Manhattan Company/Trump Building—the Flatiron differs from them all as it resembles the shape of an Ancient Greek column, with the base and apex of the building slightly thicker than the rest of it.8 The Flatiron building also was one of the first buildings to effectively utilize the elevator that was invented in 1853, was initially only twenty floors tall with the additional floor being built in 1905, and the building contained a design oversight that excluded women’s restrooms, a problem that was sloppily fixed by alternating the designation of the restrooms for men and women between floors.9

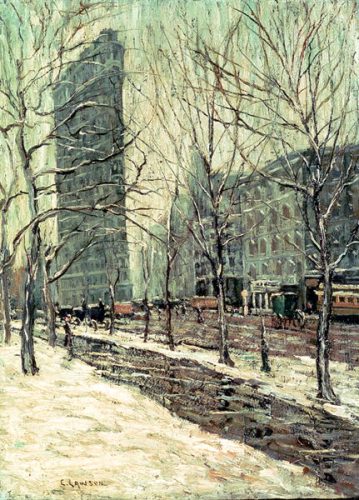

The location of the Flatiron Building on the corner of Fifth Avenue and Broadway and its unique architectural style largely played into the building’s speedy shift from a simple building into a defining symbol of New York City. Centrally located on the island of Manhattan, it has, like many other buildings in downtown New York City like the Empire State Building, ascended past its label as a building and has instead come to symbolize the city and all of its best attributes. The Flatiron being on Fifth Avenue places it on the central artery of the city, with many parades and public celebrations held on that street frequently. Additionally, the Flatiron being so close to Madison Square, Madison Square Park, and—until it was moved in 1925—Madison Square Garden further emphasized the building’s emergence as a symbol of community and the city during the 20th century. The Flatiron Building’s distinct design, location, and significance have also drawn many artists to it. The building is and has been the subject of numerous paintings—as seen in Figure 310—and photographs, with some claiming that due to its popularity amongst tourists that it is amongst the most photographed buildings in the world. At just a glance, the Flatiron Building has come to represent the Big Apple; Broadway performances, the mixing of cultures, exquisite cuisine and fine dining, exclusive shops, and its designation as one of the largest economic centers of the world are all just a few of the values that New York City has traditionally been associated with that the building has, to some degree, co-opted. Simply observing the building’s excellent architecture and the city surrounding it evokes feelings of awe and grandeur in viewers not only because of the building’s strengths but also due to what the building has come to symbolize. The building is frequently referenced in pop culture and colloquially by those not even residing in the city, though for a time it was only done so in conjunction with or in the context of anything related to New York City. Evidence of people referring to the building as its own entity and breaking this tradition can be found as early as 1932, in an article published by TIME Magazine. The article, discussing German inventor Hermann Honnef’s thoughts on his ability to create a tower for electricity production in Berlin, states: “‘Give me the money,’ said he, ‘and I guarantee to build in Berlin a tower three times taller than the Empire State Building with windmill vanes each as large as the Flatiron Building in New York.'”11 While the subject matter is not of significance here, Honnef’s rhetoric that references both the Empire State Building and the Flatiron Building represents the notoriety of the Flatiron on an international stage. Colloquial references to the Flatiron in this fashion exemplifies how widely renowned the building had become by 1932.

Though this small mention of the building is one of the first instances in which the Flatiron is referenced (for the most part) outside the scope of New York City, it is not the last. In fact, due to the Flatiron’s surge in popularity, it is far more likely that the Flatiron Building, barring its destruction, will never stop being referenced in such a way for the foreseeable future, furthermore representing how the building has become a quintessential symbol of New York City.

References

Primary Sources:

Detroit Publishing Co. “Flatiron Building, New York, N.Y.” Library of Congress, U.S. Congress, 1 Jan. 1970, https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2016800374/.

Jackson Daily News. “Wind Whirlpool.” Newspapers.com, Jackson Daily News, 10 Feb. 1903, https://www.newspapers.com/clip/52796756/wind-whirlpool/.

“Lower Fifth Avenue before the Flatiron Building.” Ephemeral New York, 27 June 2011, https://ephemeralnewyork.wordpress.com/2011/06/27/what-was-there-before-the-flatiron-building/.

“Mill & Dole.” TIME Magazine, vol. 19, no. 22, 30 May 1932, pp. 16–16. Time Magazine Archive, EBSCOhost, https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=sso&db=tma&AN=54797019&site=eds-live&custid=s8475574. Accessed 23 Feb. 2022.

“The Flatiron Building, New York, c.1903-05 (oil on board).” Bridgeman Images: Christies Collection, edited by Bridgeman Images, 1st edition, 2014. Credo Reference, https://go.openathens.net/redirector/shu.edu?url=https%3A%2F%2Fsearch.credoreference.com%2Fcontent%2Fentry%2Fbridgemanchris%2Fthe_flatiron_building_new_york_c_1903_05_oil_on_board%2F0%3FinstitutionId%3D441. Accessed 23 Feb. 2022.

Secondary Sources:

Alexiou, Alice Sparberg. The Flatiron the New York Landmark and the Incomparable City That Arose with It. Dunne Books, 2013.

Gillon, Edmund Vincent, and Henry Hope Reed. Beaux-Arts Architecture in New York: A Photographic Guide. Constable and Co., 1988.

Jackson, Kenneth T., and New-York Historical Society. The Encyclopedia of New York City. 2nd ed, Yale University Press, 2010. EBook Community College Collection (EBSCOhost), https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=sso&db=e900xww&AN=568249&site=eds-live&custid=s8475574. Accessed 23 Feb. 2022.

The Encyclopedia of New York City, published by the Yale University Press, leaves its readers with a myriad of information about the five boroughs of New York City. There are two sections that give great information about the Flatiron Building and the Flatiron District.

White, Norval, et al. AIA Guide to New York City. Fifth edition, Oxford University Press, 2010. EBook Academic Collection (EBSCOhost), https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=sso&db=e000xna&AN=2096328&site=eds-live&custid=s8475574. Accessed 22 Feb. 2022.

This guidebook discusses the history of New York Cities’ well-known buildings and landmarks. It has a section regarding the history of the Flatiron Building and discusses the architectural decisions made by its designers Daniel Burnham and Frederick Dinkelberg.

Additional Sources:

History.com Editors. “Flatiron Building.” History.com, A&E Television Networks, 22 Apr. 2010, https://www.history.com/topics/landmarks/flatiron-building.

Margolies, Jane. “End of an Era for the Flatiron Building.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 28 June 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/06/28/nyregion/flatiron-building-nyc.html

- Jackson, The Encyclopedia of New York City, 2010.

- Alexiou, The Flatiron the New York Landmark and the Incomparable City That Arose with It, 2013.

- unknown, “Lower Fifth Avenue before the Flatiron Building” 1884.

- Alexiou, The Flatiron: The New York Landmark and the Incomparable City That Arose with It, 2013.

- Gillon and Reed, Beaux-Arts Architecture in New York: A Photographic Guide, 1988.

- Jackson Daily News, “Wind Whirlpool,” 1903

- Detriot Publishing Co., “Flatiron Building, New York, N.Y.,” 1901.

- Gillon and Reed, Beaux-Arts Architecture in New York: A Photographic Guide, 1988.

- History.com Editors, “Flatiron Building,” 2011.

- Lawson, “The Flatiron Building, New York, c.1903-05 (oil on board),” 1905.

- Mill and Dole, TIME Magazine, vol. 19, issue 22, 1932.

🙂