The 1964-1965 World’s Fair in New York was not the first World’s Fair to take to place, it was not even the first World’s Fair New York had held in Flushing Meadows-Corona Park. The event was not even officially recognized as a World’s Fair. Despite these elements of the exposition the Fair made a name for itself in not just New York history, but global history as it uniquely captured plenty of contemporary issues and ideas in its pavilions. The Fair took place in Flushing Meadows Corona Park Queens, the land of which was completely changed and transformed during the years leading up to the World’s Fair, with some of the construction and terraforming remaining in New York to this day decades after the Fair’s conclusion. The Fair is notable for not only capturing the futuristic optimism of postwar 20th century America, but for also providing a lens to less favorable topics of the time such as the cold war and the civil rights movements. The Fair was also known to be perhaps one of the most theatrical displays of American capitalism and production with corporations funding some of the most famous pavilions and attractions. The Fair ended with some cloud of controversy, with its financial toll being an omen to any future World’s Fair. The remnants of the event can still be found in Corona Park with most of them withering away to time, however these structures still get some public attention every now and again when they are occasionally brought up with plans of renovation or demolition, the park however is still used and maintained.

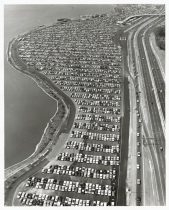

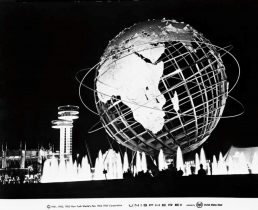

The idea to host the New York World’s Fair came from an interesting source. It came from a lawyer by the name of Robert Kopple who believed that the education of the 1950s-60s did a poor job teaching youth about different people of the world. He remembered his time as a concessionaire at the previous World’s Fair held in New York and thought it did a good job of bringing different people together. He then tracked down the past New York World’s Fair leaders and proposed the concept to both D.C. and NYC. Mayor Robert F. Wagner of New York City liked the idea as he was looking for a way to celebrate the three hundredth anniversary of England’s takeover of the city from the Dutch and the idea was pitched (the fact that it was also the twenty-fifth anniversary of the previous New York World’s Fair was coincidental, but entirely welcomed by the planners)[1]. Despite efforts from the Fair’s committees and leaders to gain recognition from the Internationle de Exhibitions located in Paris, it was not approved because the 1964 World’s Fair was not sponsored by the host government in fact the fair organizers looked to turn a profit and charged a rental fee for all exhibitioners. This would lead to Great Britain and France to not participate in the Fair, as well as a number of other countries in contrast to previous World’s Fairs[2]. However, the organizers did originally try to apply for Paris’ recognition of the event and sent a delegation. Washington D.C. had its own reasons for desiring to host a World’s Fair held in New York City despite its proximity to the 1961 World’s Fair being held in Seattle (whose representatives spoke out against the U.S. holding two fairs so close together time wise), President Eisenhower was disappointed in the United States’ performance at the 1958 Brussels Universal Exposition and thought that the nation’s pavilion was out done by Soviet display of military hardware and space technology[3]. This ultimately led to the federal government appropriating 300,000 dollars to carry out the Fair[4]. New York would commit twenty-four million dollars to the New York Fair Corp., an organization which also dealt with school system finances, but would require the Fair to create “permanent improvements” and the creation of a permanent park at the end of the run time[5]. It was also decided during the meeting between Congress and the Fair’s organizers that the event would take place from 1964-65, the Fair is to take place on the site of the 1939-40 World’s Fair, Purpose of the Fair is “Peace through understanding” and theme is Man’s achievements in an expanding universe, with a symbol of the Unisphere presented by the United States Steel Corp., and the fairground was split up into five sectors: industrial, international, transportation, Federal and State, lake area[6]. Besides the funding being provided by the Federal and State governments as well as the City the Fair would receive 40 million dollars of financing coming from private investors and make its money back through ticket sales that cost adults two dollars and one dollar for children, however, this did not include parking which was an additional dollar or reduced admission rates for multiple ticket books. Ultimately NYC was chosen as the city to host the World’s Fair over other competing cities such as L.A., Chicago, and D.C. because of its central position both in global politics and finances by the mid 20th century. It was also decided that the multicultural atmosphere of New York City would work hand and hand to the Fair’s focus of bringing the world together through understanding. One major selling point for the Federal government’s choice in NYC over D.C. was the fact that Corona Park would be rented to the World’s Fair organizers and vendors for an extraordinary low price. The “corona dump” as it was referred to would be rented out by New York City’s commissioner of parks Robert Moses for a single dollar per year. Parks commissioner Robert Moses would end up being the President of the Fair and organization after already establishing himself as New York’s go to city and park visionary. Perhaps because of this the Fair was made “accessible by parkways, expressways, bridges, tunnels, railroads, subways and buses, ships and planes” the organizers also relied on highways that were newly financed by the Federal and State governments with 20,000 parking spots prepared for cars[7]. Moses himself was a strong believer that American cities, homes, neighborhoods, and lives should be dictated by the power of the car.

Many of these infrastructure projects made for the 1964 World’s Fair would remain in place after its closure. At the end of congressional meeting in 1961, 51 countries signified their intention to participate at the World’s Fair and Robert Moses made Herbert Hoover, Harry S. Truman, and Dwight D. Eisenhower honorary chairmen of the event after they gave their blessing and support of the occasion.

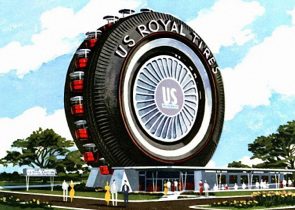

The World’s Fair would open on a chilly and rainy Wednesday morning at exactly 9:00 a.m. on April 22, 1964[8]. It was also opened with a gigantic parade of “four thousand people [who] marched in the morning parade, which featured not only Montana cowboys, kimono-clad Japanese geishas, Hawaiian hula dancers, and a group of Shriners but also such beauties as Miss America, Miss Universe, and Donna Reed. Music included Scottish bagpipes, a Caribbean steel-drum band, an Israeli accordionist, strolling Spaniards with guitars, and the University of Pennsylvania marching band.” The glamorous and over the top parade would be just the start of the intriguing and captivating displays waiting for attendees. The fair had many attractions such as the RCA Pavilion allowing visitors to be filmed on live color tv cameras and displayed on a color television, riding a brand new car model (the Mustang) at the Ford Pavilion, using two way visual and audio communication at the Bell Telephone Pavilion (the Picturephone), IBM’s new machine (the computer), or General Electrics’ display of a real thermonuclear demonstration[9]. Given that this was also during the height of the space race and Cold War, National achievements and technological demonstrations of American power such as rocket ships that had entered orbit were also shown off in the space park. Perhaps the most interesting and possibly popular attraction though, was Michelangelo’s Pieta loaned and displayed by the Vatican at the fair, a notable exhibit since it was the first time the piece was displayed outside of its Vatican home in its entire 465 year existence this was along side of The Dead Sea Scrolls.

The Vatican had actually been working closely with the committee who prepared the Fair due to the nature of the event’s purpose: peace through understanding[10]. Walt Disney had a heavy hand in many of the attractions. The Anaheim park had been open for a decade by the opening day of the World’s Fair and so inspiration such as fountains leading up to and surrounding the Unisphere as well as direct Disney exhibitions were shown off, such as “It’s a Small World” run by Pepsi or animatronic president Lincoln run by the Illinois Pavilion or General Electric’s “Carousel of Progress”. Some of these rides would be broken down and rebuilt by Disney in his California park or moved to Florida in preparation of his new Magic Kingdom.

Not every pavilion was a showy performance of international dancers and musicians, nor were they all amusement park rides such as the ones sponsored by Pepsi and GE. Some of the pavilions were walk around displays such as that of the Pavilion of American Interiors, which was still in grand scale to match the other Fair demonstrations with a luxurious circular four story building to display all sorts of modern American home goods and designs. The building fit right into the other corporate funded pavilions with the building and furniture/goods inside promoting the wonders of American capitalism and materialism [11]. The display of American home extravagance was rooted in a much larger political conflict just as the rest of the Fair was, it was ultimately a World’s Fair to demonstrate America’s position as the champion globally and especially compared to Soviet Union. This was accomplished through small features such as restaurants to larger projects such as mock supermarkets or entire entertainment rides built by American corporations to show off not only new American technology, but industrial might and surplus [12]. Not every performance and show held by the Fair was seen with as much fanfare as the amusement park rides that Walt Disney had constructed for several corporations or originally designed with the obvious messages of American capitalism and superiority. In fact, one of the most controversial moments during the World’s Fair’s showtime was President Johnson’s speech for peace. Despite having an overall uncontroversial message of equality and peace throughout the world, Johnson had failed to mention the escalation of the Vietnam war or reference the racial segregation and civil rights movements that the nation found itself being swept by. Because of this between two days the president’s speech was interrupted by those calling for the end of “Jim Crow” followed by outcries of “Freedom now”[13]. The speech and its reaction was a loud reminder to the injustices and hypocrisy of the nation hosting the World’s Fair. Perhaps because of its position on the global stage the fair would continue to be a location of politics and protests with groups such as the NAACP or Spanish American War veterans outside the Spain pavilion defying Moses’ direct wishes of keeping the Fair “politics free”, an arguably impossible task with the context of what was going on in the world and domestically in the U.S.[14]. Despite the memorable rides and newsworthy demonstrations of societal unrest abroad and at home, the main thing remembered by most American Fair goers were the delicious Belgium Waffles.

The end of the fair was arguably disastrous, at least financially for the vendors and investors. Culturally the Fair and its vision for the future would remain in Americans’ and global Fair goers’ mind for decades, not to mention for anyone who did attend the Fair they were overall satisfied and enjoyed their experience. However, the fair was a financial catastrophe, whereas the 1939-1940 New York World’s Fair had investors receive a sixty to forty cent return per dollar spent the 1964 Fair had a 19.2 cent return[15]. This was on top of controversy surrounding the financing of the Fair during the two-year run and was due in part to lower than expected attendance (which was originally calculated with a questionable method). In light of this New York was left with a newly improved Corona Park which still to this day has some remnants of the Fair, namely stone labels and pavilion signs in the pathways or in the form of large construction projects that were never removed at the end of the Fair such as the New York observation towers and the Unisphere. Despite falling into disrepair in the decades after the Fair’s runtime many of the older structures and park infrastructure are being conserved and renovated with some even making their way on to historic preservation lists[16].

Bibliography

Foderaro, Lisa W. 2014. “In Queens, the Fate of a Towering Relic From the 1964 World’s Fair Is Debated.” The New York Times, February 18. https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=sso&db=edsgit&AN=edsgit.A358925767&site=eds-live.

Caro, Robert. 1974. The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York. New York: Knopf. ISBN 978-0-394-48076-3. OCLC 834874.

Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library. “Aerial view of fair. [Parking lot]” New York Public Library Digital Collections. Accessed April 25, 2022. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/917ac730-5e61-bc61-e040-e00a18067a62

Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library. “Unisphere at night.” New York Public Library Digital Collections. Accessed April 25, 2022. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/916b2d9f-4a02-3c46-e040-e00a18067754

Molella, Arthur P., and Scott Gabriel Knowles. “9. Cold War Food: Consumption and Technology at the New York World’s Fair, 1964–1965.” In World’s Fairs in the Cold War : Science, Technology, and the Culture of Progress. University of Pittsburgh Press, 2019. https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=sso&db=edspmu&AN=edspmu.MUSE9780822987086.17&site=eds-live.

Samuel, Lawrence R. 2010. The End of the Innocence : The 1964-1965 New York World’s Fair. Syracuse, N.Y.: Syracuse University Press.

United States. Congress. House. Committee on Foreign Affairs. Subcommittee on International Organizations and Movements. 1961. Planning United States Participation in the New York World’s Fair : Hearing before the Subcommittee on International Organizations and Movements of the Committee on Foreign Affairs, House of Representatives, Eighty-Seventh Congress, First Session, on H.R. 7763, and Other Bills, to Provide for Planning the Participation of the United States in the New York World’s Fair, to Be Held at New York City in 1964 and 1965, and for Other Purposes, August 10, 1961. Washington : U.S. G.P.O. https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=sso&db=edshtl&AN=edshtl.MIU01.102746547&site=eds-live.

Young, William P. “Pavilion of American Interiors.” The Website of the 1964/1965 New York World’s Fair. Accessed April 27, 2022. http://nywf64.com/legacies01.shtml.

[1] Samuel, Lawrence R. 2010. The End of the Innocence : The 1964-1965 New York World’s Fair. Syracuse, N.Y.: Syracuse University Press, 3-4

[2] United States. Congress. House. Committee on Foreign Affairs. Subcommittee on International Organizations and Movements. 1961. Planning United States Participation in the New York World’s Fair : Hearing before the Subcommittee on International Organizations and Movements of the Committee on Foreign Affairs, House of Representatives, Eighty-Seventh Congress, First Session, on H.R. 7763, and Other Bills, to Provide for Planning the Participation of the United States in the New York World’s Fair, to Be Held at New York City in 1964 and 1965, and for Other Purposes, August 10, 1961. Washington : U.S. G.P.O. 9

[3] Samuel, 5

[4] United States. Congress. House. Committee on Foreign Affairs. Subcommittee on International Organizations and Movements, 1

[5] United States. Congress. House. Committee on Foreign Affairs. Subcommittee on International Organizations and Movements, 2

[6] United States. Congress. House. Committee on Foreign Affairs. Subcommittee on International Organizations and Movements, 2-3

[7] United States. Congress. House. Committee on Foreign Affairs. Subcommittee on International Organizations and Movements, 4

[8] Samuel, 32

[9] Samuel, Introduction

[10] Samuel, Introduction

[11] Young, William P. “Pavilion of American Interiors.” The Website of the 1964/1965 New York World’s Fair. Accessed April 27, 2022. http://nywf64.com/legacies01.shtml.

[12] Molella, Arthur P., and Scott Gabriel Knowles. “9. Cold War Food: Consumption and Technology at the New York World’s Fair, 1964–1965.” In World’s Fairs in the Cold War : Science, Technology, and the Culture of Progress. University of Pittsburgh Press, 2019. 110

[13] Samuel, 34

[14] Samuel, 37

[15] Caro, Robert. 1974. The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York. New York: Knopf. ISBN 978-0-394-48076-3. OCLC 834874.

[16] Foderaro, Lisa W. 2014. “In Queens, the Fate of a Towering Relic From the 1964 World’s Fair Is Debated.” The New York Times, February 18.