A New Tool to Analyze an Evolving Governance Landscape

To the Global Health Governance Blog

To the Global Health Governance Blog

In May 2011, the World Health Assembly received the report of its International Health Regulations Review Committee examining responses to the outbreak of the 2009 H1N1 pandemic influenza and identifying lessons to be learnt. This will emphasized the need for better risk communication in the future. But risk and communication are not objective facts; they are socially mediated cultural products. Responses to crises are not simply determined by the situation at hand, but also mental models developed over protracted periods. Accordingly, those forces responsible for promoting the precautionary approach and encouraging the securitization of health, that both helped encourage a catastrophist outlook in this instance, are unlikely to be held to scrutiny. These cultural confusions have come at an enormous cost to society.

The concept of human security is increasingly accepted as being integral to contemporary notions of national security because of a growing awareness of the importance of individual and societal well-being to national, regional and global peace and stability. Health is thus considered an important component of the predominant vision of human security. However, the precise meaning and scope of global health security remains contested partly due to suspicions about clandestine motives underlying framing health as a security issue. Consequently, low and middle-income countries have not engaged global discourse on health security. This has resulted in an unbalanced global health security agenda shaped primarily by the interests of high-income countries. It narrowly focuses on a few infectious diseases, bioterrorism and marginalizes health security threats of greater relevance to low and middle-income countries. Focusing primarily on countries in the WHO-AFRO region (the African Group), this paper examines the implications of the participation deficit by the African Group of countries on their shared responsibility towards global health security. The potential benefits of regional health security cooperation are analyzed using selected critical health security threats in the Southern African Development Community (SADC). This paper concludes that the neglect of the African Group health security interests on the global health security agenda is partly due to their disengagement. Ensuring that multilateral health security cooperation includes the African Group’s interests require that they participate in shaping the global health security agenda, as proposed in a putative SADC health security cooperation framework.

With their increased emphasis on soft power, both the Bush and Obama Administrations have opened up a new front in the war of ideas regarding who will have the most influence over developing countries as the world moves through the twenty-first century. Currently the political and philosophical differences between the parties of this conflict are not as starkly defined as they were in George Kennan’s historic argument for containment (i.e., there is no “Evil Empire,” and “terrorism” can be a process, act, or method, but not a state). Yet the consequences of losing this international war on poverty have been defined as no less than a tangible threat to U.S. national security interests and moral leadership. This paper narrowly focuses on one particular type of strategy in this new war—foreign aid for health—and how, by helping countries to supply and train more of their own soldiers in this type of fight (i.e., non-physician health workers and surgically trained workers) the United States can achieve the best results in terms of sustainability, cost, and regional impact.

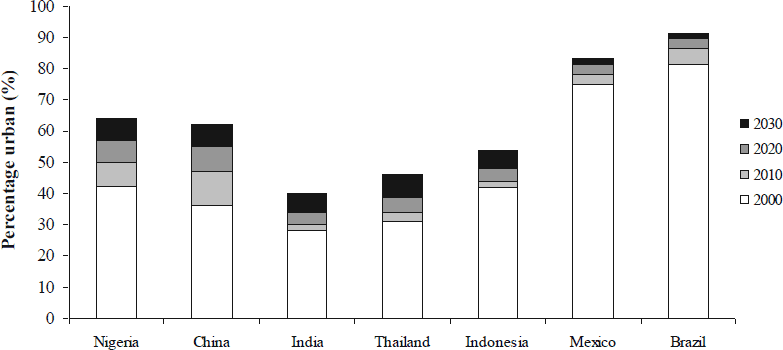

In 2008, the world’s urban population exceeded its rural population for the first time. The United Nations estimates that about 15% of the world’s population now lives in “megacities” of 10 million or more people, or in near-megacities of 5-10 million. Three-quarters of the megacities are in low- and middle-income nations, where rural-to-urban migration will drive rapid urbanization through 2050. Services and infrastructure rarely keep pace with population growth. Even in well-resourced cities, municipal leaders struggle with urban sprawl, unmet housing and transportation needs, environmental degradation, and disaster vulnerabilities. In the absence of adequate resources and regulation, informal settlements and markets evolve fluidly, creating shelter and livelihoods but also exposing inhabitants to environmental risks that exacerbate health inequities. These problems might once have been considered local challenges. Now, these “international cities” are often cross-roads for the movement of people, animals, and goods (and the health risks that they carry), as well as drivers of national or regional economic development. New strategies are needed to govern the flow of health risks within and among these densely populated urban centers. The breathtaking scope of the challenges that urbanization poses for development and security can only be understood by looking at long wave events that cross sectors, disciplines, and borders. Tools such as the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control and the International Health Regulations (2005) can affect the flow of health risks between regions, but cannot substitute for strong planning, policy, and management functions at the municipal level – exactly where governance capacities tend to be weakest.

Over the last 15 years public health challenges have increasingly been framed as security threats, arguably leading to increased political relevancy and funding for such public health challenges as HIV/AIDS. While maternal health has not yet been securitized, there are several reasons to believe that it could be in the future. Such a securitization of maternal health could increase funding and political relevancy, important for improving maternal health outcomes. At the same time, we believe there are many unconsidered risks of such an approach. The risks we have identified are long-term unknowns from a lack of research, increased politicization of aid at the expense of effective programs, unexpected funding challenges due to geopolitical priorities, gender concerns, and the blurring of civilian and military institutions. Our goal is not to present a structured framework for analyzing the securitization of maternal health, but to begin a debate about the positive and negative aspects of securitization, and the dangers of securitization that we believe have been inadequately considered to date.

Following the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks, the US military expanded its global health engagement as part of broader efforts to stabilize fragile states, formally designating “medical stability operations” as use of Department of Defense (DoD) medical assets to build or sustain indigenous health sector capacity. Medical stability operations have included medical assistance missions launched by US Africa Command and in other regions, deployment of hospital ships to deliver humanitarian assistance and build capacity, and health-related efforts in Afghanistan and Iraq. The public health impact of such initiatives, and their effectiveness in promoting stability is unclear. Moreover, humanitarian actors have expressed concern about military encroachment on the “humanitarian space,” potentially endangering aid workers and populations in need, and violating core principles of humanitarian assistance. The DoD should draw on existing data to determine whether, and under what conditions, health engagement promotes stability overseas and develop a shared understanding with humanitarian actors of core principles to guide its global health engagement.

Rising concerns about the human, political, and economic costs of emerging infectious disease threats and deliberate epidemics have highlighted the important connection between global public health and security. This realization has led security communities, particularly in the U.S., to seek ways to bolster the international health response to public health emergencies as a means of protecting national security. While there have been important recent efforts to strengthen international response to infectious disease threats, there are areas that deserve more attention from both the health and security communities. In this article, we describe two important gaps in international frameworks that govern the response to global public health threats which can negatively affect the security of states: (1) despite attempts to strengthen international rules for responding to public health emergencies, there continues to be strong disincentives for states to report disease outbreaks; and (2) systems for detecting and responding to outbreaks of infectious diseases are hindered by a lack of standards of practice for sharing biological samples and specimens. To address these gaps in global governance of infectious disease threats, additional incentives are needed for states to report disease outbreaks to the international community; there should be greater enforcement of countries’ international health obligations; and both political and scientific communities should develop workable practice standards for sharing biological samples of all types.