Uganda’s Government Turns to New Pretexts to Justify Electoral Corruption

Collin Duran

Staff Writer

Uganda has a muddled history when it comes to national elections. President Yoweri Museveni has led Uganda for nearly forty years and, on January 14, the president won a sixth in national elections, reports NPR. The election was marred by accusations of corruption and intimidation tactics used by the government. Domestic media outlets rushed to report on these abuses and cited the COVID-19 pandemic as a driver behind violations of the right to a free and fair election. The validity behind the narrative that the pandemic caused violations of civil liberties and impeding democratic institutions is insubstantial. The actions taken by Museveni’s government during the most recent election reflect a pattern of abuse in the electoral process. While there is no doubt that COVID-19 played a role in enabling the government to impede the electoral process, a closer look reveals that the pandemic is merely a new pretext for old crimes.

Uganda’s most recent election was littered with accusations of electoral abuse. Prominent opposition leader Kyagulanyi Ssentamu, better known as Bobi Wine, his supporters, journalists, and Ugandan voters were subjected to constant harassment by the government during the campaign period. While the scale of electoral violations is not unprecedented, government explanations for the abuse have shifted. Police subjected Wine to constant harassment throughout the election process, leading eventually to his arrest. The Ugandan government claimed that Wine’s incarceration was a direct result of him breaking COVID-19 restrictions with the size of his rallies, states Human Rights Watch.

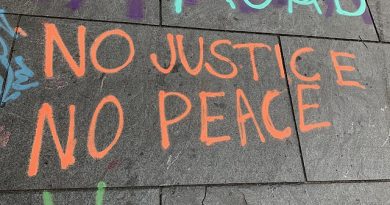

Bobi Wine’s arrest led to a sweeping of protests across the country, some of which were met with brutal violence from state police resulting in 45 deaths and 600 arrests, The New York Times reports. In the days following Wine’s arrest, the Ugandan electoral commission halted rallies in areas across the state, citing coronavirus concerns, though these areas had already been visited by President Museveni in previous months, reports Bloomberg. Additionally, The New York Times notes that there are credible allegations that President Museveni also hosted large rallies that exceeded the 200 person limit mandated by coronavirus guidelines.

These measures taken by the Ugandan government to suppress opposition during the most recent election are not new and also appeared during the country’s 2006, 2011, and 2016 elections. This pattern reveals a consistent history of attacking the electorate, opposition leaders, and journalists.

One notable incident in the recent 2021 election was the throttling of internet services in the days leading up to the election. According to NPR, the government shut down social media services such as Facebook, Twitter, and WhatsApp. Additionally, military vehicles and soldiers were deployed into the capital city of Kampala, where Wine draws most of his support. These actions parallel the 2016 election. A report from the Global Observatory notes that on the day of the 2016 election, the internet was shut off, and military personnel present in the capital. While neither the 2011 nor the 2006 elections featured an internet shutdown by the government, they did include the same voter intimidation tactics in Kampala, a historically weak region for President Museveni. A report from Reuters notes that there was an increase in armored vehicles, riot police, and military personnel in Kampala on the day of the 2011 election. A 2006 report from CNN shows that there was a similar situation during the election that year. Attacks on the electorate have become the new norm in Uganda. The electorate is not the only group the government is willing to go after, as the Museveni administration has launched slander campaigns against prominent opposition leaders.

The 2006 Ugandan election, similar to the subsequent elections in 2016 and 2021, featured smear campaigns against Museveni’s main opposing candidate. In 2006, Museveni ran against a former confidant, Kizza Besigye. Besigye’s campaign was hindered by various forms of government interference and criminal charges, including rape allegations, for which he had to appear in court, reports The Guardian. Max van den Berg, the EU’s chief observer for national elections, noted that the charges brought against Besigye were, “trumped up in order to damage him politically.” The Museveni government used the court system to slow the momentum of the Besigye campaign during the 2006 election. However, the slander campaigns did not stop in 2006.

The 2016 election saw Museveni and Besigye run against each other for the fourth straight election. During the campaign period, Besigye was placed under house arrest for hosting illegal public rallies that violated the Ugandan Election Commission’s mandate that all rallies be held indoors, reports by The Guardian. The government’s crackdown on public rallies directly correlates with Museveni’s desire to dampen growing populist support for opposition leaders, ensuring his 2016 election win. Besigye disputed the result, reports Al Jazeera, but was placed under house arrest on the grounds that his actions were treasonous.

The 2021 election featured the same harassment of the opposition. With Bobi Wine as Museveni’s new challenger, the incumbent’s campaign turned to COVID-19 as a pretext for immobilizing and slandering Wine, who was arrested twice for supposedly breaking pandemic guidelines. Like Besigye, Wine was placed under house arrest following the announcement of the election results under the pretense that a public appearance by the politician would incite riots, notes the Associated Press. The government has not limited itself to attacks on the electorate and opposition candidates. The Museveni administration has also been openly hostile towards the media.

The Ugandan government has muzzled the country’s press in the previous four elections while offering different justifications each time. The government has not been shy in resorting to both physical and non-physical harassment in its attempts to curb media criticism. During the 2021 election, three journalists were hospitalized following a scuffle in the country’s Masaka District, reports Voice of America. When members of the media were given an opportunity to enter into a dialogue regarding media harassment, the commissioner of the Uganda People’s Defense Force, Brigadier General Henry Matsiko, quickly shot down any discussions of abuse. The commissioner went on to accuse members of the media of being one-sided in their reporting, calling them activists and saying, “once you’re a journalist, prove to us, that you are exercising professionalism.”

The Museveni administration has also used the COVID-19 pandemic as a justification for limiting foreign journalists from entering the country. A report from the Council to Protect Journalists highlights how the Ugandan government amped up security clearance requirements for members of foreign media organizations entering the country. All foreign journalists were required to re-apply for accreditation to cover any electoral events, a process described by the Council to Protect Journalists as “onerous” in nature. The new accreditation process also required journalists to submit personal information and a portfolio of their work. The new process made it clear that the Ugandan government could be selective in who is allowed to observe the election. Additionally, foreign media members were threatened with legal repercussions if they violated the new protocol and attended electoral events without accreditation.

Abuse towards the media did not begin in 2021, but the government’s justifications for violating the freedom of the press has transformed. The 2006 elections featured numerous instances of journalists being harassed by local police and military personnel. A 2006 report from Human Rights Watch outlined how two separate members of the media were charged with promoting “sectarianism” for penning critical stories about the Museveni government. Additionally, when Besigye was on trial for rape and treason, the Ministry of Information forbade media outlets from covering the case, saying it could potentially create “prejudice” in the political leader’s trial. In the days leading up to the 2011 election, two journalists were shot while reporting at opposition lead rallies, reports the Committee to Protect Journalists. In the months following the 2011 election, Museveni openly slammed both foreign and domestic media companies for their coverage of protests throughout the country, notes The Guardian. The 2016 elections presented the same hostile environment for journalists. Robert Ssempala of the Human Rights Network for Journalism stated to Voice of America that during the 2016 electoral cycle, there were over 80 incidents of, “violations and abuses of media rights and freedoms.” This treatment of journalists shows that the Ugandan government is not afraid of using any justifications to bar members of the media from criticizing the regime.

The coronavirus pandemic has shaken the world in a multitude of ways, forcing countries around the world to make societal changes necessary to adapt to the new reality. The Ugandan government, on the other hand, has approached the pandemic from an opportunistic standpoint. During Uganda’s 2021 national election, President Museveni and his administration used COVID-19 guidelines and regulations as an excuse to double down on old practices. As in previous elections, Ugandan citizen’s right to a fair and free electoral process was violated with the government’s usage of intimidation tactics and harassment measures.