Access to Education in the Age of the Coronavirus

Collin Duran

Staff Writer

2020 has been referred to as a year of “reckoning” for the United States. The country currently facing a devastating pandemic, a catastrophe catalyzed by an inadequate government response and a lack of strong centralized leadership throughout the outbreak. But the pandemic has exposed more than just our country’s inability to respond to a nationwide health crisis – it has brought attention to what income inequality looks like in a time of emergency. The education system has not been spared from this “reckoning” either. Coronavirus has exposed an empty commitment to education in the United States and has highlighted the effects of severe income inequality on students and their educational experience.

Income inequality in the United States is currently rivaling levels of inequality not seen since the Gilded Age. A study done by the RAND Corporation, a global think tank, and reported by TIME Magazine, concluded that, “had the more equitable income distributions of the three decades following World War II (1945-1974) merely held steady, the aggregate annual income of Americans earning below the 90th percentile would have been $2.5 trillion higher in the year 2018 alone.” The think tank ultimately concluded that roughly $50 trillion between 1975 and 2020 has been taken from the paychecks of those in the bottom 90 percent of income earners. Naturally, this growing income inequality, and the missing $1,144 in paychecks of every American in the bottom nine deciles, has had a major impact on educational opportunities for students, especially those in the lower middle class and lower class.

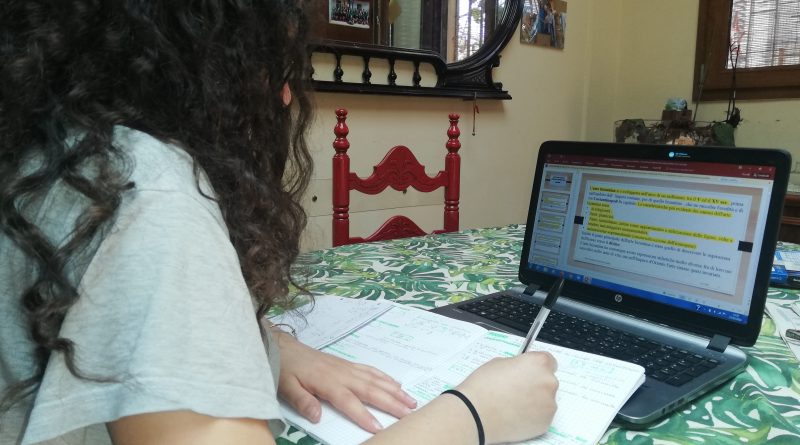

The biggest impact income inequality has had on education in the age of COVID has been in the ability of students to simply have access to school at all. With schools across the country trying to adapt to remote learning and varying hybrid schedules, the one constant in all reopening plans is remote learning, an approach that requires access to advanced technology and the internet. For many, these tools are easily accessible and commonly taken for granted (I admittedly include myself in this category). However, for students coming from rural communities, low-income households, and the homeless, there is a real struggle to obtain either one of the necessary tools for distanced education.

The Pew Research Center surveyed parents throughout the pandemic and found, “some 43% of lower-income parents… say it is very or somewhat likely their children will have to do schoolwork on their cellphones; 40% report…their child having to use public Wi-Fi to finish schoolwork because there is not a reliable internet connection at home, and about one-third (36%) say it is at least somewhat likely their children will not be able to complete schoolwork because they do not have access to a computer at home.” These statistics are staggering but are not surprising. Educators have clamored about concerns for equal access to education for their low income and minority students even before the pandemic. Now, those issues are being emphasized like never before.

Westfield State University Provost and Vice President of Academic Affairs, Dr. Diane Prusank served this role during the spring semester of 2020 and outlined how, “low-income students find themselves facing at least four different problems: lack of access to hardware (i.e. a fully functioning computer), lack of access to software (specialized software for areas of study), lack of access to the internet (including access to reliable internet service), and a lack of resources in the home.” The issues she discussed parallel what we see in public education from elementary to high school, a problem that will only worsen in the coming months.

As reported by the Washington Post, “several big city school districts are now projecting 15 to 25 percent cuts in overall revenue going into next school year.” This significantly lowers the chances for the most financially challenged students to receive the resources necessary to attend school.

One of those impacted cities is New York City. The public school district currently serves 114,000 homeless students, reports The New York Times; students who, “rely on school buildings for meals, physical and mental health services, and stability.” Without the ability to physically attend school five days a week, these students are forced to scour the city for public internet, for a place to charge a broken iPad, or for a quiet room where they can do their homework. While those who need educational opportunities the most slug their way through the city looking for any resource they can find to attend school, the Council on Foreign Relations states the wealthiest families hire teachers for “microschooling” classes for their kids in their own homes.

The views expressed in opinion articles are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the values of The Diplomatic Envoy.