From Listserv at American University

On July 29, 1853, by the Bull Apostolici ministerii, Pope Pius IX established the Diocese of Newark. Since 1808 the southern half of New Jersey had been part of the diocese of Philadelphia, the northern half part of the diocese of New York. Now the Catholics of the state were united under the bishop of Newark. The news did not arrive until September, and Father Senez immediately tendered his resignation as pastor to Bishop Hughes. The bishop-designate, Rt. Rev. James Roosevelt Bayley, appointed Rev. Bernard McQuaid as pastor.

First Bishop of Newark (1853-1872)

Archbishop of Baltimore (1872-1877)

From Frederick J. Zwierlein, The Life and Letters of Bishop McQuaid

James Roosevelt Bayley, nephew of St. Elizabeth Ann Bayley Seton, Foundress of the Sisters of Charity, was consecrated a bishop on October 30, 1853 in “Old” St. Patrick’s Cathedral on Mott Street in New York City by the papal nuncio to Brazil, Archbishop Gaetano Bedini, who had been travelling in the United States and was then en route to Rome. Bayley designated St. Patrick’s Church as the “pro-cathedral” of the diocese of Newark. This indicated that the role was temporary until a “proper” cathedral could be built. The ceremonies that marked Bayley’s installation indicated that the life of St. Patrick’s would be changed for many years to come.

The Right Reverend Bishop arrived in Newark on November 1, All Saints Day, to take possession of his See. It was a perfect Indian summer day. A procession of thousands escorted the bishop from his train to the pro-cathedral, where Bayley was received by Father Moran, senior priest of the diocese. Moran made a brief address of welcome and introduced the clergy to their new bishop. The pro-cathedral was jammed to overflow for the ceremonies and the Pontifical Mass that followed. Father McQuaid was quite carried away by the occasion. After Mass, the clergy were entertained at a banquet at his expense. Father McQuaid sold his horse and carriage to pay for it.

From Frederick J. Zwierlein, The Life and Letters of Bernard McQuaid

From Frederick J. Zwierlein, The Life and Letters of Bernard McQuaid

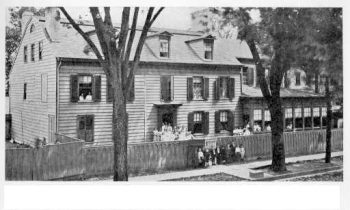

Bishop Bayley and Father McQuaid brought the Sisters of Charity to Newark and to St. Patrick’s. Two sisters from Mount St. Vincent’s established the first community in the old Ward mansion on the corner of Washington and Bleecker Streets. These pioneers were Sister Mary Xavier Mehegan and Sister Mary Catharine Nevin. McQuaid had been unhappy with the administration of the Orphan Asylum and asked the sisters to take it under their care.

The euphoria of the episcopal installation soon was dampened. On September 5, 1854, the Orange Association, also known as the American Protestant Association, marched 3,000 strong through Newark. St. Mary’s Church on High Street was wrecked and looted. Within St. Mary’s a damaged statue of the Blessed Virgin remains as mute reminder of this outrage. The sisters at St. Patrick’s gathered the orphans into the church, locked the doors and remained there through the night. Father McQuaid walked among the crowds and did his best to persuade angry Catholics to disperse. Later, he unsuccessfully demanded prosecution of the attackers, but succeeded in seeing responsibility for the violence placed on the Orangemen.

Rector of St. Patrick’s Pro-Cathedral 1853-1868

From Frederick J. Zwierlein, The Life and Letters of Bernard McQuaid

In September 1856 Bishop Bayley opened a college, Seton Hall, in Madison, and named Father McQuaid its first president. St. Patrick’s busy pastor now took on the additional responsibilities of college president. He resigned after his first year, but was re-appointed president in 1859, remaining as pastor of St. Patrick’s. St. Patrick’s was an energetic and thriving community. The Rosary Society was so numerous it had to be divided into two sections. He also founded the Young Men’s Catholic Association, which throughout the 19th century numbered several thousand young men in its ranks. The association’s object was “to improve its members by affording them opportunities for wholesome and innocent recreation, and uniting them in fraternal charity.” According to an 1891 program, “the association is now in its thirty-eighth year…the leading young men’s Catholic organization of New Jersey, and the first of its kind to be established in the United States.” McQuaid built the Catholic Institute on New Street as a cultural and social facility for the association and as an alternative to the neighborhood saloon. It included a reading room, lecture hall, billiard parlor and gymnasium, and sponsored a wide range of lectures, dramatic productions and other activities.

Throughout the 1850s, the vibrancy of the parish was evidenced by over 1,000 children in the catechism classes and about 700 in the school. Each year there were about 250 First Communions. All of these activities were supported by collections that, in 1855, amounted to almost $10,000. More than half of this came in the form of “pew rent.” Into the early part of the twentieth century, parishioners literally could “rent” a pew. It was reserved for their use during one or all of the Sunday Masses and other devotions and events. For this reason the pews in St. Patrick’s are numbered — lest someone mistakenly enter the wrong pew.

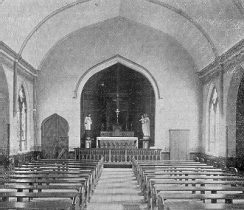

The transformation of St. Patrick’s from a simple parish church to a cathedral necessitated physical changes. Soon after he became pastor, McQuaid began the first of a series of renovations and additions to the building. The original church did not have a proper sacristy, a place for clergy to vest and for storage of vestments and other liturgical articles. As a cathedral, ceremonies increased in number and complexity. St. Patrick’s was now the site of ordinations, Pontifical Masses, and episcopal consecrations. To address this need, Father McQuaid constructed the sacristy that runs around the rear of the church proper. Owing to the proximity of the school he was hampered for space, hence the narrow and odd appearance of the structure. The small tower with its conical roof is connected to the sacristy and is topped with a “rooster weather-vane.” These weather-vanes are very common on Protestant churches in New England, which prefer the rooster to a cross. However, the rooster is also a symbol of vigilance that awakens us to the light of Christ, the rising sun.

Courtesy of the Archives of the Archdiocese of Newark

at Seton Hall University

The number of people attending weekly Mass, parish missions, and pontifical ceremonies often filled the church to overflow. An article in the Newark Daily Advertiser noted that “At the principal services at present the Cathedral is crowded to inconvenience with devout worshipers and the additional chapel will undoubtedly prove a great relief. It will be capable of accommodating about 400 persons.” Funds were collected and, in 1859, the Chapel of St. Vincent de Paul was erected. Situated on the left side of the church, the chapel was open to the body of the church. Originally there were no pews, only benches. This allowed parishioners to face the church for a ceremony taking place at the main altar, or to face the rear of the chapel where there was another altar for Mass. The same year saw the installation of the Stations of the Cross by Bishop Bayley.

Perhaps the most spectacular embellishment of St. Patrick’s was the installation of the bishop’s chair. According to tradition, early bishops preached and taught, not from a pulpit, but from a chair in the sanctuary of the church. The Latin word for chair is cathedra, from which comes the word “cathedral.” Over the centuries, the bishop’s chair took on the appearance of a royal throne. Few monarchs can claim a throne as glorious as that provided by Father McQuaid for the bishop of Newark in St. Patrick’s Pro-Cathedral. McQuaid engaged John Jelliff for the project. Jelliff was Newark’s most prominent furniture, chair, and cabinet maker of the last half of the 19th century. His achievement is spectacular. The throne “is made of black walnut, gracefully carved, and extends upward of 20 feet, where it projects forward about six feet and culminates in pinnacle shape at the height of about 25 feet…Various devices of a religious and ornamental character, including a representation of two angels under the projection above, are ingeniously carved upon it.” Interestingly, what appears to be the throne is actually a great canopy. The chair itself is small, low-backed, and uncomfortable. The cost was about $1,000. Jelliff also designed the cover of the baptismal font and probably the credence table in the sanctuary. The font cover now serves as a canopy over the tabernacle in the chapel.

Courtesy of The Star Ledger

The secession of the southern states in 1860 and 1861 brought on the most bitter conflict in the history of the United States. Both Bayley and McQuaid were intensely loyal to the Union cause. Bishop Bayley’s Diocesan Register carries the following entry: “Today we hoisted the American Flag at the Cathedral, it being the day of a Union Meeting. Father McQuaid made a speech in front of the Court House.” The Newark Evening Journal reported that McQuaid’s appearance was met by “an enthusiastic outburst of applause, which was kept up for several minutes.” The burden of this war, like most others, fell most heavily on the poor. Historians note the disproportionate number of Catholics of Irish extraction in the army of the United States. Draftees were allowed to pay $500 for a replacement. To the Irish immigrants, this was a fortune. Yet St. Patrick’s sent many of her sons to the bloody battlefields of the American Civil War.

Not only the sons of St. Patrick’s, but also the pastor, heeded the call to arms. He volunteered to be an army chaplain but was forbidden by Bishop Bayley. Later in the war, he visited the front and ministered to dying soldiers at Fredericksburg, Virginia. Late in life, Bishop McQuaid loved to tell his seminarians of how he made a convert through whiskey. A wounded Protestant soldier, through a long, weary, sleepless night, watched intently how McQuaid ministered small doses of whiskey to a fellow soldier in critical condition from his wounds. Later, this soldier told McQuaid that if it was his faith that taught him to care for his neighbor in such a manner, he also wished to be a Catholic.

Civil War did not prevent St. Patrick’s from continuing to develop. The great tower was given a voice. On December 7, 1862, Bishop Bayley solemnly consecrated a peal of four bells. The largest, named St. Patrick, weighed 3,000 pounds, followed by St. Mary at 1,536, St. James at 888, and little St. Bridget, only 375. Cast by A. Meneeley’s Sons of West Troy, NY, these bells had an aggregate weight exceeding three tons. At the time these bells were the largest in the city.

After the end of the Civil War in 1865, an already rich parish life continued to expand. Adult organizations included the Rosary Society, the Blessed Sacrament Society, two sodalities, three temperance societies, the Apostleship of Prayer and the St. Vincent de Paul Society. While some of these societies addressed strictly spiritual activities, others had a more practical and social service focus. Alcoholism, considered a personal failing in the nineteenth century, was especially prevalent among the poor. Temperance societies supported “drunkards” to the best of their ability. The St. Vincent de Paul Society organized the parish’s outreach to the poor, helping families of unemployed, widows and orphans.

St. Patrick’s opened a separate school for boys in 1866 with the arrival of the Brothers of the Christian Schools, the De La Salle Christian Brothers, under the direction of Brother Gustavus. On opening day 240 boys enrolled. In the 19th and into the 20th century, many educators considered the separation of boys and girls as an ideal. Few Catholic parishes were able to maintain separate schools due to the increased costs. St. Patrick’s was one of these few. The Cathedral Schools educated over 1,200 students, and more than 2,500 were enrolled in Catechism class. Each year there were nearly 600 baptisms. St. Patrick’s was educating twice as many students and baptizing twice as many babies as ten years before. Yet due to the hardships of the post-Civil War years, it achieved these goals with about three-quarters of the income it received in the 1850s.

In 1868 Father Bernard McQuaid, pastor of St. Patrick’s Pro-Cathedral, president of Seton Hall College, rector of Immaculate Conception Seminary, vicar general of the diocese of Newark, was raised to the episcopate as bishop of Rochester, New York and consecrated by Archbishop McCloskey in St. Patrick’s Cathedral in New York City.

McQuaid’s successor as pastor was almost turned away the first time he came to St. Patrick’s Rectory. One Saturday night, after confessions, George Hobart Doane, deacon in Grace Episcopal Church, dropped into St. Patrick’s and told Matthew O’Brien, the sexton, that he wanted to see Bishop Bayley. Mr. O’Brien sent him to the rectory. At the rectory, Bishop Bayley had retired. It was after 11 p.m., and he asked the visitor to call at a more reasonable hour. Young Doane refused to leave and the Bishop finally received him. The two spent half the night talking. Influenced by the Oxford Movement, and the example of Bayley himself, Doane asked to be received into the Roman Catholic Church. On Sept. 22, 1855, Bayley wrote in his diary: “Today I baptized George Hobart Doane, son of the Protestant Episcopal Bishop of New Jersey.” Doane was ordained in St. Patrick’s Cathedral on Sept. 13, 1857 by Bishop Bayley, himself a convert from the Episcopal Church.

After conversion, he was officially deposed from the ministry of the Episcopal Church by his father, Bishop George Washington Doane. Some years later, Father Doane was invited to preach in the Catholic church of Burlington, the episcopal see of his father. Bishop Doane remarked, “Well, I see the prodigal is coming home. Then we must kill the fatted calf.” The bishop sent ornaments from his home and flowers from his garden for the adornment of the altar in the local Catholic church. That evening, over a family dinner, father and son were reconciled. Doane was assigned to the pro-cathedral as assistant pastor under McQuaid, and during the Civil War, served as chaplain to the New Jersey Brigade in the midst of some of the harshest fighting. He was to remain as pastor of St. Patrick’s longer than anyone before or since, thirty-seven years.

Hard times continued as the pastorate shifted from Father McQuaid to Father Doane. Parish life was stable, societies prospered, and the schools remained full. St. Patrick’s Schools, like all parish schools, depended on the sisters and brothers who staffed them. Not only were they trained and competent to teach the required “Three ‘R’s”, they taught religion in the parish schools and in the Sunday school. As vowed religious, they only received a minimal stipend paid to their religious congregation. In 1871, the Sisters of Charity who conducted the Girls’ School and the Christian Brothers who conducted the Boys’ School, received a total of $3,400 for the entire year. Their sacrifices enabled the parochial school system to grow and thrive. It was in the parochial schools and Sunday schools that these dedicated women and men transmitted the faith to young Catholics.

In 1872, four years after Doane assumed the pastorate, James Roosevelt Bayley, founding bishop of Newark, was named archbishop of Baltimore. It was not until the next year that the 33-year-old Rt. Rev. Michael Augustine Corrigan was named as Bayley’s successor. St. Patrick’s Pro-Cathedral was the site of his episcopal consecration on May 4, 1873. This ceremony was enhanced by the “Cathedral Singers,” a choir established to provide music for the many episcopal ceremonies as well as for parish events. Like his predecessor, Doane faced additional responsibilities since his parish was also the seat of the bishop. The cathedral continued to be the site of ordinations to the priesthood, numerous pontifical ceremonies, weddings of prominent persons, including future United States Senator James Smith, Jr., and a wide range of other activities. The rectory often held receptions and dinners for archbishops, apostolic delegates, and other prominent ecclesiastical figures.

Pastoral needs were not neglected. The societies continued and flourished. The size of the parish can be judged by the figure of 270 confirmations in 1874. That same year the Forty Hours triduum brought over 2,500 to communion, a very significant figure because, at the time, frequent communion was rare. Most would not approach the altar rail without going to confession immediately before. For such a number of communions, we can be sure that an almost equal number of confessions were heard. “Missions” of several days, even of a week’s duration, were frequent. Prominent speakers, including Father Isaac Hecker, founder of the Paulist Fathers, addressed separate groups of men and women. The missions encouraged repentance, confession and communion. Often they were an occasion for people to return to the practice of the faith and for couples married civilly to have their marriage solemnized in church. It was not unusual for more than one thousand men or women to attend, go to confession and receive communion. Each mission was followed a few month’s later by a “renewal.” At the renewal, the people were called to remember resolutions made at the mission. The next year the cycle of mission and renewal would begin again. Each year during Lent, special Lenten Conferences took place during Sunday Vesper services. The topics of these conferences varied but they were normally instructional. They provided an opportunity for adults to learn the Church’s teaching on the sacraments and other aspects of the faith.

The poor were a continuing concern. The parish followed Irish tradition and collected the “orphan’s shilling” on a regular basis. Special collections brought about $3,000 per year to the St. Vincent de Paul Society. The Christmas Midnight Mass was very popular and the pro-cathedral required an offering of $.25 per person. The proceeds, usually over $300, went to the poor as well. The $300 income tells us that more than 1,200 parishioners jammed the church for Midnight Mass. This income is quite extraordinary for the time. The financial “Panic of 1873” had set off a long economic depression. It was so bad that Bishop Corrigan commented that “in consequence of the hard times many of our churches have been robbed of their sacred vessels.” The resources of the parish were strained by the increasing needs of people out of work. Yet the generosity of the parishioners did not weaken.

In 1871, a new cross was placed on the spire, the old one having lasted just over twenty years. Doane also enriched the church with statues purchased from the studio of Franz Meyer in Munich, one of the most prominent purveyors of quality church furnishings. Among these is the statue of the Sacred Heart. The inscription beneath records its solemn blessing by Bishop Corrigan on December 8, 1873. The dedication of the statue marked the consecration of the diocese of Newark to the Sacred Heart of Jesus. The Irish Americans of St. Patrick’s demonstrated their devotion by placing the statue on a pedestal decorated with shamrocks. Doane also purchased an enormous “Nativity Set” that was placed before the altar of the Blessed Virgin for Christmas that year. Bishop Corrigan described “the Stable at Bethlehem” as “occupying the entire chapel.”

« The Parish | Renovation »