Courtesy of the Archives of the Archdiocese of Newark at Seton Hall University

Little more than twenty years had passed since St. Patrick’s was opened. Yet, in 1874, it was deemed necessary to undertake major renovations. Its status as a cathedral required some changes. Father Doane also noted that “the walls are actually shabby…not only the appearance, but also the safety of the building requires that these repairs be made.” He lamented “worn out windows…the organ that was almost beyond repair…the incompleted chime.” Another reason for renovation was a plan to consecrate the pro-cathedral. When a church is opened it is blessed and dedicated to worship. However, church law requires that before a church can be consecrated, it must also be free of debt. St. Patrick’s was almost debt free. The consecration of the church would require fundraising to pay for renovations. Over $30,000 was raised in one year so that the consecration could take place. The pro-cathedral was officially debt-free.

Jeremiah O’Rourke, one of Newark’s best-known ecclesiastical architects, and a parishioner of St. Patrick’s, was placed in charge of the renovation. St. Patrick’s had not been designed to be a cathedral and the existing sanctuary was too small for elaborate ceremonies. Six front pews were removed to provide space for an expanded sanctuary. To this day the front pews in the church carry the numbers “7” and “8.” In addition, St. Patrick’s was painted “inside and out.” In the 19th and early 20th centuries, it was not unusual for brick buildings to be painted. The old organ was sold to St. Michael’s Church in Jersey City. Henry Erben built the new organ. Truly of cathedral dimensions, it was composed of 1,948 pipes.

Six new bells, cast by Meneeley & Co. of Troy, New York, were installed in the spire. Consecrated by Bishop Corrigan on February 21, 1875, they joined the four installed in 1862. They are St. John the Baptist, weighing 2,100 pounds, St. Peter & St. Paul, Apostles, weighing 1,262, St. Gabriel, Archangel, weighing 648, St. Aloysius, Confessor, weighing 534, St. Rose of Lima, Virgin, weighing 456, and tiny St. Cecilia, weighing only 280. They cost $2,800. With the bells, a carillon was installed. The following year, St. Patrick’s bells celebrated the Fourth of July by pealing Let the Triumph Sound, Hail Columbia, Fling Out the Nation’s Starry Flag, ’Tis Midnight Hour, The Battle Cry of Freedom, Let Erin Remember, Te Deum Laudamus, Columbia The Gem of the Ocean, The Harp That Once Thro’ Tara’s Halls, The Blue Bells of Scotland, Sublime Was the Warning, The American Flag, The Sword of Bunker Hill, The Minute Gun at Sea, Irish Melody, and Old Folks at Home. No one in Newark could doubt the patriotism of the members of St. Patrick’s Parish. With the installation, the total weight of the bells increased to almost 12,000 pounds, or six tons. This put a great strain on the spire and caused it to weaken. A century later it became necessary to silence the bells lest the spire collapse.

The old stained glass was sold for $1,000 and new windows were installed by “Mr. Fitzpatrick, the ‘glass stainer.’” Over the sanctuary, the new windows depicted Our Lord with the Blessed Virgin and St. Joseph Adoring; St. Patrick, St. Bridget, St. Columbkille, and St. Laurence O’Toole; and St. Michael, St. George, St. Francis of Assisi, and St. Vincent de Paul. These windows would be replaced fifty years later.

The elaborate ceremony of consecration by Bishop Corrigan took place on March 17, 1875. Archbishop Bayley came from Baltimore for the occasion. He was joined by St. Patrick’s former pastor, Bishop McQuaid of Rochester and Archbishop John Williams of Boston. As part of the ceremony, the relics of Saints Faustinus, Constantius, and Bonosa, Martyrs, were inserted in the altar. Twelve candles, indicating a consecrated church, were placed on the walls. They are traditionally lit each year on the anniversary of the consecration. After the ceremonies, Bishop Corrigan celebrated a Pontifical High Mass and Archbishop Bayley preached. Bayley spoke to the enormous congregation that had filled the cathedral.

You have proved your love by the piety and devotion with which you have aided the zealous efforts of your pastor in beautifying and decorating this old parish church, this pro-cathedral of St. Patrick’s…It is the house of God and the Gate of Heaven. We as good Catholics should carry out the spirit of our forefathers and make our churches noble and worthy of the worship for which they are designed. We should do all in our power to adorn them and provide generously for them, that their worship may be grand and solemn, as the best means by which we may give God the supreme worship and honor which belongs to Him.

The banquet that followed was truly festive as Bishop Corrigan had dispensed the Diocese of Newark from the Lenten rule of abstinence from meat.

Just two years later, Archbishop Bayley returned to St. Patrick’s for his final visit to the Newark he loved. His health had failed and he had sought relief at European spas to no avail. The archbishop arrived in Newark in August 1877, and two months later, on October 3, he died in his old room in the episcopal residence on Bleecker Street. The Newark Daily Advertiser reported that “the remains rest in the room in which he died, the face turned toward the Cathedral altar, in which direction he was wont to gaze longingly and lovingly during his illness.” Bishop Corrigan offered a Solemn Mass for him on October 5, and his body was returned to Baltimore for another Mass. He was buried in Emmitsburg next to his aunt, Mother Elizabeth Ann Seton.

Father Doane was one of Newark’s best-loved citizens. A turn of the century historian recounts that he “was the principal motor and the most gratified witness of the origin and progress of the majority of Newark’s Catholic institutions. Churches, hospitals, schools, orphanages and academies sprang up under his watchful care.”

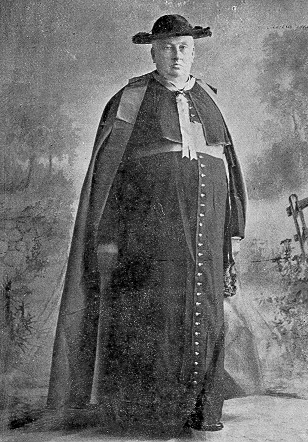

Father Doane went on a 15-month European tour in 1878-1879. He visited the shrines of Lourdes and Paray-le-Monial and in Rome was received in audience by Pope Leo XIII. He also visited the Mothers General of Little Sisters of the Poor, and of the Sisters of the Good Shepherd. His return provoked one of the grandest receptions in the history of Newark. Newspaper accounts describe a cheering crowd of 30,000 filling the streets, Protestants and Catholics alike waving flags of welcome. Father Doane, in an open carriage, escorted by torch-bearing parishioners, processed in triumph from the train station to the cathedral. Cries of “God bless ye, Father Doane,” “Welcome home, Father Doane,” “O, the sight of ye is good” were heard on all sides. Throughout the procession, fireworks, skyrockets, and various pyrotechnic displays filled the sky. When he arrived at the cathedral, the bells chimed Home Again. A year later, Father Doane became Monsignor Doane when Bishop Corrigan announced his appointment as a prelate of the Papal Household. On April 23, 1880, he was formally invested as a domestic prelate at a High Mass attended by over 100 priests and a distinguished congregation that included a former governor. The cathedral choir sang LePrevost’s Mass, composed for the coronation of Emperor Napoleon I in 1804.

Courtesy of the Archives of the Archdiocese of Newark

at Seton Hall University

As usual, problems followed upon triumph. Two months later, in June, gales damaged the parish buildings, especially the schools. In Bishop Corrigan’s words, “the tin roof of the Cathedral Schools was rolled up, like a scroll, and carried off into the street.” After the schools were repaired, the parish decided to erect a new, stronger, and larger school. The school building, designed by Jeremiah O’Rourke, which still stands on Central Avenue, was completed in 1888. A few years earlier, in 1884, Doane had attended the Third Plenary Council of Baltimore as an expert advisor to the bishops. That council reaffirmed the importance of parochial schools and directed the formulation of what became known as the Baltimore Catechism. The Baltimore Catechism was quickly integrated into the religion curriculum of the pro-cathedral schools. Over the years, several generations of Catholics would be introduced to the faith through its progressively more difficult questions and answers. The first question set the foundation in noble simplicity: Question. “Who made the world?” Answer. “God made the world.”

St. Patrick’s Cathedral Golden Jubilee Booklet of 1900 recognized Doane’s interest in education in its tribute to the pastor.

Monsignor Doane is a great advocate of Catholic schools, and but a few years ago erected the magnificent structure of St. Patrick’s School, which stands next to the church. He loves his dear children, and the earnest prayer which goes up from their young hearts today is “God Spare Dear Monsignor for the Celebration of His Golden Jubilee in the Priesthood.”

Unfortunately, Monsignor Doane was to die two years short of this goal.

During the intervening years, the Diocese of Newark underwent transition. In 1880 Bishop Corrigan was named coadjutor archbishop of New York. The following year, the diocese of Newark was divided, Newark retained the seven northern counties of New Jersey, the remainder were assigned to the new diocese of Trenton. Monsignor Doane was named administrator of the diocese until a new bishop was appointed.

Rt. Rev. Winand M. Wigger was named bishop and was consecrated in St. Patrick’s by Archbishop Corrigan on October 18, 1881. Wigger and Doane were far from close friends. Wigger’s first act was to change most of the clergy appointments made by Doane during his tenure as administrator. He declined to re-appoint Doane as vicar general of the diocese. Finally, he attempted to remove Doane as pastor on the grounds that the bishop was the real pastor of the cathedral. He failed and Doane remained. In light of this disagreement it is understandable why Bishop Wigger did not occupy the episcopal residence on Bleecker Street, which doubled as the residence of Doane, pastor of the pro-cathedral. Eventually, the two men reconciled and no enduring estrangement resulted. In 1889, Monsignor Doane was elevated to the rank of protonotary apostolic, a promotion made by the pope usually upon the recommendation of the bishop. This gave Monsignor Doane the privilege of celebrating Pontifical Mass four times a year, wearing miter, cross, and ring.

“The Gay Nineties” were not a pleasant time for Newark, which found itself once again in the midst an economic downturn from 1893 through 1897. “Times are so bad,” Doane wrote to the bishop, “that many people simply cannot give.” He asked to be excused from the “Peter’s Pence” collection for the pope because it was doomed to failure. Things had been so poor, he added, that for the first time he was not able to pay the sisters the money that was due to them. The parish did its best, the St. Vincent de Paul Society, as usual, was in the forefront of relief efforts. In 1898, just as the economy began to improve, America went to war with Spain. Many Catholics, including parishioners of St. Patrick’s, were torn by this conflict. The United States was fighting a Catholic nation and some of the rhetoric had an anti-Catholic tone. President William McKinley announced that one of his aims in annexing Catholic colonies such as the Philippines and Puerto Rico was “to Christianize them.” Catholics naturally took offense.