Courtesy of the Archives of the Archdiocese of Newark

at Seton Hall University

With the 19th century drawing to a close, St. Patrick’s Pro-Cathedral began to plan a celebration of its Golden Jubilee. As planning went on, the parish had some unexpected and unwanted excitement. The New York Times issue of January 8, 1900 reported:

Insane Man in Cathedral

Attempts to Leap from a Gallery

Alarming Many ChildrenNewark NJ, Jan.7.- There was considerable excitement in St. Patrick’s Cathedral during the 8 o’clock mass this morning caused by the attempt of an unidentified man, who had become temporarily crazed, to jump from the gallery. The cathedral was crowded with children at the time, and had not the man been seized when he was dangling from the gallery rail he would have fallen onto the heads of a number of children.

The man was first noticed praying devoutly in the aisle of the north gallery. Suddenly he made a dash down the aisle and attempted to jump over the railing. Several men who were in the front seats on either side of the aisle seized him and a struggle ensued. During the struggle he shouted, wildly, “Let me go! let me go!”

When finally pulled back over the railing the man was taken away by friends, who refused to disclose his identity.

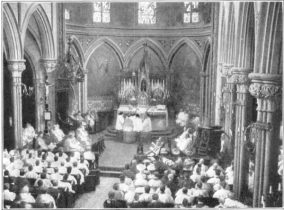

With great pomp and ceremony, St. Patrick’s celebrated the golden jubilee of the dedication of the church. The Golden Jubilee Booklet noted that St. Patrick’s anniversary’s coincided with the Church’s Worldwide Jubilee celebrations — a coincidence that would, of course, reoccur.

It is with pardonable pride that the good people of Old St. Patrick’s, emulating the praiseworthy example of so many of their fellow Catholics throughout the country, in this auspicious year of the Church’s jubilation, have joined together in celebrating, in becoming manner, the fiftieth anniversary of the foundation of the temple of God, erected for their special benefit, under the titular patronage of the immortal and ever glorious apostle of the Isle of Saints. In the spirit of the Christian jubilee, banishing care and sorrow from their hearts, they contemplate with indescribable joy the glory of this day of Jubilee.

The booklet gives us a snapshot of life over 100 years ago. Advertisements for the Eagle Brewing Company, Essex County Brewing Company, and Lyons and Sons Brewing Company remind us that Newark once was something of a beer-capital. In addition to these and the usual suppliers of ecclesiastical and parish furnishings were advertisements for:

The Edison General Electric Company

Incandescent Lamp Factory

R. Van Buskirk, 10 Academy Street

Immediately Relieve and Permanently Cure Whooping Cough in One Week — Together with Malaria, Rheumatism, etc.

J. Newton Van Ness Co., Established 1795

Fine Harness, Saddles, Bridles, Horse Clothing, Etc.

Everything for a Horse

120 Chambers Street, 50 Warren Street

New York Dental Parlors, 188 Market Street

We Challenge the World to Equal Our Teeth without Plates

Full Set of Teeth that Fit – $5.00.

While most of the advertisers have faded from memory, one illustrates an unfailing dedication to the youth of Newark.

St. Vincent’s Academy

42 Wallace Place

Newark, N.J.St. Vincent’s Academy, under the direction of the Sisters of Charity, reopened Tuesday, September 6th. The course of instruction pursued at this Institution comprises all the branches of a thorough English education — Music, Painting, Needlework and Plain Sewing. French, German and Latin taught in all grades throughout the Academy. Children over four years of age will be admitted to the Kindergarten.

Within a year, the diocese of Newark would mourn the death of Bishop Wigger. On Christmas Day 1900, he celebrated Pontifical Mass and Vespers at the pro-cathedral. Two days later, he experienced the first symptoms of pneumonia. Just before midnight on January 5, 1901, he died at his home in South Orange. Five days later, on January 10, his funeral took place at St. Patrick’s. On the following July 25, in the pro-cathedral, Archbishop Corrigan consecrated Rt. Rev. John J. O’Connor as the fourth bishop of Newark. One year later, Archbishop Corrigan, Newark’s second bishop, died in New York.

From Joseph Flynn, The Catholic Church in New Jersey

Five years after the turn of the century, Monsignor Doane passed away. So highly regarded was he that Newark citizens of all faiths contributed to a fund for a memorial. A life-sized statue of Doane in his prelatial robes was erected in tiny Rector Park just north of Trinity Episcopal Cathedral, now Trinity and St. Philip’s Cathedral, on Broad Street. It was unveiled with imposing ceremonies on Jan. 9, 1908. Whether by accident or design, the statue faces west, looking towards St. Patrick’s, of whose cross Monsignor Doane once wrote, “glittering in the sunlight it would flash upon my eye as if to tell me that there alone would He be found Who died for us upon it.”

In a half-century events had come full circle for the Catholics of Newark. Just fifty years earlier, riots provoked by the Orange Lodge had torn the city, forcing the sisters and children to hide in the cathedral. A short time before in Elizabeth, Mrs. Mary Whelan had defied Know-Nothing rioters who attempted to destroy her church. She held her child in her arms and dared the rioters to pass. The mob dispersed. The baby who played a part in this dramatic incident eventually was ordained a priest. He was Isaac P. Whelan who became the fourth pastor of St. Patrick’s Pro-Cathedral, in succession to Monsignor Doane. When he assumed the pastorate in 1905, one-quarter of the population of northern New Jersey adhered to the Catholic faith.

Like his predecessors and successors, Monsignor Whelan faced the challenge of aging buildings. Shortly after coming to St. Patrick’s, Whelan extensively redecorated the church. The Shanley family, relatives of Mother Seton and of Archbishop Bayley, had long been generous contributors to the parish. Mrs. Julia D. Shanley donated more than half of the $18,000 cost. New side altars and Stations of the Cross were erected and a altar rail of marble and bronze installed. The chapel was transformed into a baptistery, the font placed in the small apse where there had been an altar. Electric lighting was installed.

In 1908 Whelan engaged Jeremiah O’Rourke to design and oversee the construction of a new rectory on Washington Street. The brick and limestone rectory included a suite for the bishop, perhaps hoping to induce the Bishop of Newark to move back from South Orange. The cost of the rectory was $30,000. The number of sisters serving the parish had increased and two years later, O’Rourke designed the new convent, called the “Sister House,” facing Bleecker Street, in a similar style at a cost of $21,000. It was able to comfortably accommodate sixteen Sisters of Charity. Interestingly, provision was made for both gas and electric lighting in each building.

Courtesy of The Star Ledger

In the years since St. Patrick’s was opened in 1850, the number of Catholic churches in Newark had grown from three — St. John’s, St. Mary’s, and St. Patrick’s — to 23. In the last half of the 19th century immigration had brought millions of Europeans to the United States. As the century drew to a close, the pattern of immigration shifted. While in the mid-19th century almost 90% of immigrants came from northern and western Europe, by the 1890s, more than half were from eastern and southern Europe. As early as 1875, Bishop Corrigan had ordered a census of the Italian-speaking Catholics in Newark, and assigned an Italian priest, Rev. Joseph Borghese, to minister to them at St. Patrick’s. The new churches reflected the growing diversity of the Catholic population. Some, like St. Patrick’s, served a predominately Irish population. Others were called “national” parishes and served a particular immigrant group, Germans, Italians, Poles, and Lithuanians.

Not only was the ethnic composition of Newark Catholicism changing but some very basic changes in Catholic practice were introduced by the new pope, Pius X, elected in 1903. Pope St. Pius X believed that the Eucharist had become too remote from the people. For centuries, Catholics rarely approached the Eucharist. Some received Communion just once a year, the minimum required by Church law since the 13th century. Pope Pius encouraged Catholics to receive Communion frequently, even daily. For Catholics this was a startling change and it would take many years for daily, or even weekly, Communion to become commonplace. The pope realized this and also changed the regulations for First Communion. He reduced the age for first reception of Communion from twelve to seven years of age.

In the early years of the 20th century, at St. Patrick’s, it was Monsignor Whelan who presided at the First Communion Masses of these youngsters. The Sisters of Charity and the Christian Brothers prepared them for this momentous occasion. The education and attention this change required may be likened to the change in the liturgy from Latin to English and other modern languages during the last third of the 20th century. As in the past, the people of St. Patrick’s adjusted to change.