The New York City Civil War Draft Riots of 1863: Four Days of Unrest

On the morning of July 13th, 1863, the American Civil War had been ongoing for two years. The Emancipation Proclamation was issued by President Lincoln on the first of that year, freeing the slaves. The battle of Gettysburg had claimed its lives, just over 200 miles away, earlier that month, where there were between 46,000 and 51,000 casualties.[1] 23,050 New Yorkers took part in the battle; around 1000 were killed, 4,000 injured, and 2,000 were presumed either captured or missing.[2] Riots broke out in New York City in response to the draft list published by the government, lasting until July 16th, 1863. The riots resulted in more than 100 lives lost, $1.5 Million damage, and about 2,000 injured. Police could not control the mobs, and the chaos was only quelled when the army stepped in. The draft riots remain the largest civil and racial uprising in American history, apart from the Civil War itself. But what of the surrounding areas that were so close to where the riots were sparked? What happened on Manhattan Island that resonated in two of the future five boroughs of New York City? How were the people of Staten Island and Brooklyn affected? We will briefly look to the testimony of those who lived through those three days and two nights of fear and anger.

Though slavery had been abolished in New York City since 1827, race tensions were still present, especially in the workplace. “Northern labour feared that emancipation of slaves would cause an influx of African American workers from the South, and employers did in fact use black workers as strikebreakers during this period. Thus, the white rioters eventually vented their wrath on the homes and businesses of innocent African Americans” [3]. New York City was greatly affected by the war, as the economy heavily relied on shipping and the textile industry, thus relying heavily on cotton from the south. By the mid-1830s, cotton shipments accounted for more than half the value of all exports from the United States thus, “…there is a marked similarity between the trends in the export of cotton and the rising value of the slave population,” [4]indicating that New York City as a major export city relied on the South’s economic prosperity that flourished largely due to the institution of slavery. This was most likely a factor on people’s minds during this time, especially the lower working class who worked on docks and those who labored to spin and make the textiles, and that the prosperous economy of the city may be devastated. Fernando Wood, mayor of New York City, even proposed seceding from the Union to become “The Free City of Tri-Insula”.

Though free African Americans had settled and held business in and near New York City since before 1800 and slavery was abolished, racism that separated them was still present in society. A major mark of this lies in the popularity of minstrel shows. Originating in New York City in 1828, Thomas Dartmouth Rice was the first to perform a ‘comedic’, racist song and dance in ‘blackface’. Minstrel shows were widely popular in the United States, especially so in New York City, through the civil war. Irish were also subject to blatant racism in New York City. Immigration from Ireland to America peaked in the mid 1800s, and many lived in poor conditions in the 5 points neighborhood. Many were met by American Nativist sentiment and blatant discrimination, especially in the workforce as ‘no Irish need apply’ was common among job postings. Regarded as ugly, lazy drunks, many Irishworked as laborers in low paying jobs. There was competition between free African Americans and Irish workers, and this was further onset by the Emancipation Proclamation ordered by President Lincoln. There was a present fear among Irish workers that a large influx of freed slaves would enter the workforce and take jobs away from them, and to die in a war that now aimed for the freeing of said slaves was seen as more than just unfair.

Classism and increased distance between rich and poor also made itself evident. In March of that year, Congress passed the Enrollment Act, requiring “all able-bodied men” between the ages of 20-45 to enlist and serve in the military, including those who were in the process to become citizens. However, a commutation fee of $300 (equivalent to $5,775 today) could be paid to have a substitute serve in place of the giver, thus avoiding the draft. The average worker made less than $500 a year. [5]In light of all this mobs primarily comprised of the Irish working class, many who were drafted, took to the streets to protest the unfairness they felt, as only the wealthy could afford to exempt themselves from the war that many New Yorkers at the time felt was not their own.

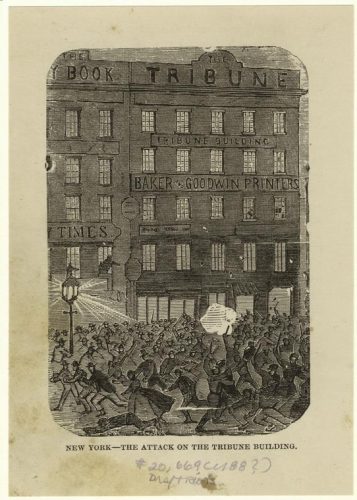

Saturday, July 11th felt hardly a stir from the people, though it was the first drawing of the draft. The morning of the second draft on Monday, July 13th was met by a crowd of about 500 people gathered on 3rd Ave and 47th street outside the ninth district provost. Here, led by ‘Black Joke’ Engine Co. No. 33, (famous for their fist-fighting skills as they were for their fire-fighting skills), the discontent mob threw stones threw the window and set the building ablaze. They dismantled any fire fighting vehicles that came, even killing horses. Rioters attacked police that responded or tried to avoid the mob after being beaten, and police stations were also destroyed The Brooks Brothers store that had been selling Union uniforms was targeted, as well as the New York Times and Tribune building, but only Brooks Brothers’ was profoundly affected by the mob. Rioters then targeted African Americans, abolitionists, and slavery sympathizers, seeing them as the new reason for the war, the reason why they were being drafted. Not only were many ‘negroes’ killed-either hung, burned, or beaten to death- but also their homes and businesses destroyed. Two churches and the Colored Orphan Asylum were among the places burned, but the orphans were evacuated before the attacks. Abraham Franklin, Augustus Stewart, Peter Heuston (a Mohawk Indian), Jeremiah Robinson (whose wife attempted to escape with him safely by dressing him as a woman, but was found out by the mob), a Mrs. Derickson (a Caucasian woman), and others were listed among the dead and injured victims of the mob. [6].

A lawyer and diarist, George Templeton Strong, was present in New York City for the duration of the riots and recorded his views and experience of the situation. “Here and there a rough could be heard damning the draft. No policemen to be seen anywhere. Reached the seat of war at last, Forty-sixth Street and Third Avenue. Houses…were burned down, engines playing on the ruins.” He goes on to describe the crowd that was there as “… a posse of perhaps five hundred [of the] lowest Irish day laborers. Every brute in the drove was pure Celtic.” [7]He goes on to comment that Jefferson Davis seemed spiritually present in the city. It is important to note the last phrase here, as Strong’s view exemplifies the upperclasses’ view of the mob and its majority Irish as ‘brute’ and something apart from them as ‘Celtic’. The Pennsylvanian-African American paper The Christian Recorder published on July 25th comments on the mob, “Just think of it, reader, that so many innocent and inoffensive of God’s human beings should be driven from their quiet homes…beaten and left almost lifeless, [many] killed dead on the spot. Oh! Such bloody, fiendish murderers will receive their reward at the hands of a just God. We are not disappointed as to the class of men generally engaged in that wicked, hellish act. The New York papers say that they were mostly Irish who were engaged in the riot; of course there were hundreds of others who may be called Americans, but the Irish were in the majority.” [8]We can see here that the African American community also had a low opinion of the Irish people in America, here being unsurprised-almost expectedly, that the mob was mostly Irish New Yorkers.

9th District Marshall Provost’s Office 1863- The Civil War Draft Riots

9th District Marshall Provost's Office 1863- The Civil War Draft Riots

The Draft Riots: Brooklyn

Brooklyn had a free black community as well, called Weeksville. Established in 1838, and allowed economic mobility, intellectual freedom, and was self-sustaining . By the 1850s, Weeksville had over 500 residents, “ boasting more opportunity for homeownership, employment and success for its black residents than any other part of Brooklyn, and well beyond.”. Many African ...

The Draft Riots: Final Thoughts and Bibliography

The riots were quelled when federal troops faced off with rioters on Thursday, July 16th, eventually ending the immediate disarray in New York City. After the riots were over, Governor Horatio Seymour addressed the people of New York City and made a statement to the rioters, “I know that many who have participated in these ...

The Draft Riots: Its Roots and Occurance

The New York City Civil War Draft Riots of 1863: Four Days of Unrest On the morning of July 13th, 1863, the American Civil War had been ongoing for two years. The Emancipation Proclamation was issued by President Lincoln on the first of that year, freeing the slaves. The battle of Gettysburg had claimed its lives, ...

The Draft Riots: Staten Island

Staten Island traditional oral history recalls the events of the initial response to the riots as a single noble defense, but in actuality had two outcomes. The main telling goes that citizens in Port Richmond, which was a ‘hop, skip, and jump’ away from Manhattan, pointed a cannon towards the bridge at Bodine’s Creek to ...

https://blogs.shu.edu/nyc-history/civil-war-draft-riots/

9th District Marshall Provost's Office 1863- The Civil War Draft Riots Brooklyn had a free black community as well, called Weeksville. Established in 1838, and allowed economic mobility, intellectual freedom, and was self-sustaining . By the 1850s, Weeksville had over 500 residents, “ boasting more opportunity for homeownership, employment and success for its black residents than any other part of Brooklyn, and well beyond.”. Many African ... The riots were quelled when federal troops faced off with rioters on Thursday, July 16th, eventually ending the immediate disarray in New York City. After the riots were over, Governor Horatio Seymour addressed the people of New York City and made a statement to the rioters, “I know that many who have participated in these ... The New York City Civil War Draft Riots of 1863: Four Days of Unrest

On the morning of July 13th, 1863, the American Civil War had been ongoing for two years. The Emancipation Proclamation was issued by President Lincoln on the first of that year, freeing the slaves. The battle of Gettysburg had claimed its lives, ... Staten Island traditional oral history recalls the events of the initial response to the riots as a single noble defense, but in actuality had two outcomes. The main telling goes that citizens in Port Richmond, which was a ‘hop, skip, and jump’ away from Manhattan, pointed a cannon towards the bridge at Bodine’s Creek to ...9th District Marshall Provost’s Office 1863- The Civil War Draft Riots

The Draft Riots: Brooklyn

The Draft Riots: Final Thoughts and Bibliography

The Draft Riots: Its Roots and Occurance

The Draft Riots: Staten Island

[1] Gettysberg Casualties, historynet.com, http://www.historynet.com/gettysburg-casualties

[2] The States at Getteysberg http://gettysburg.stonesentinels.com/battle-of-gettysburg-facts/the-states-at-gettysburg/

[3] “The Draft Riots of 1863”, Encyclopedia Britannica https://www.britannica.com/event/Draft-Riot-of-1863

[4] “The Economics of the Civil War”, Roger Ransom, https://eh.net/encyclopedia/the-economics-of-the-civil-war/

[5] “Congress passes Civil War conscription act” history.com http://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/congress-passes-civil-war-conscription-act

[6] The New York Daily Tribune, October 10th 1863 http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83030213/1863-10-10/ed-1/seq-3/

[7] “George Templeton Strong: Diary, July 13-17, 1863”, The Civil War: the Third Year Told by Those Who Lived It. The library of America.p382-389

[8] The Christian Recorder, July 25th 1863, http://www.accessible.com/accessible/print

Colored orphans Asylum located at 5th ave and 43rd street, 40.754177, -73.980421

As the draft riot remained the largest riot in the history, as the battle of Gettysburg claimed many life and even many were lost that could not be found, still New York City still remain a strong and metropolitan city till today