Lakshmi Kripalani, M.A. ’66 doesn’t have much patience for those who blame a failing public education system on lack of money. She once opened a school with little more than a bullhorn.

Lakshmi Kripalani, M.A. ’66 doesn’t have much patience for those who blame a failing public education system on lack of money. She once opened a school with little more than a bullhorn.

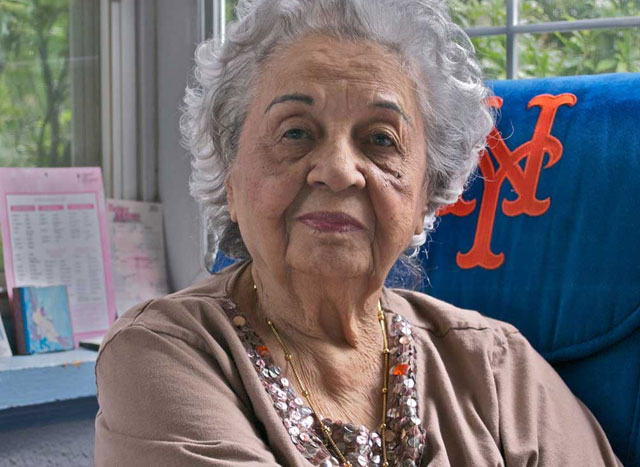

It was in India in 1947, right after the country had gained its independence, and Kripalani was just 27 years old. She and her family had fled their home in West Pakistan for a refugee camp in Bombay (now Mumbai), India. Everyone slept in tents and food was spread thin. In a hut where the milk was stored, dozens of children and their mothers were clawing at one another for a few sips. “It was what I’d call a massacre of children,” Kripalani recalls from a bright blue recliner in her home in Montclair.

The only remedy for the chaos, she thought, was education. Just a year earlier, she had been trained by Maria Montessori, the Italian doctor who created an educational movement that places children in a clean and orderly setting and allows them to direct their own learning.

And so Kripalani told the camp’s commander that the refugees needed a school. He laughed and said something to the effect of, “Lady, we can hardly feed you, and you want a school?” Kripalani insisted she needed no money, only his permission. So he gave her a bullhorn and a challenge: If you think you can build a school with this, go ahead.

She took the loudspeaker in her hands and addressed the camp. “I told them, ‘We have lost everything and our children have lost everything. If you want a school for your children, come and help me,’ ” she says.

It was an impossibly hot afternoon. But within an hour, some 150 children and 30 adults were carrying stones out of a shed that would become a school. When it opened the next morning, Kripalani sprinkled white flour and yellow curry powder on the ground to divide the room into sections of different classes. She used branches to write on the ground, and buds, flowers and pebbles to teach math.

Kripalani, who turned 91 in August, has dedicated her life to Montessori education. After two decades of teaching in India, in the 1960s she helped see the movement through a bumpy re-emergence in the United States. She’s known equally as a wise elder — she kept all of her original notes from Montessori’s lectures in India — and as a spitfire.

Since 1989, she’s written a quarterly column for the Public School Montessorian, a newspaper that is sent to every Montessori school in the U.S. These articles, which have been bound into two books, often delve into ways in which, in Kripalani’s view, Montessori schools are straying from their namesake’s original teachings. “She has a very strong sense of how classrooms should operate, and is outspoken about it,” says Dennis Schapiro, editor of the Public School Montessorian. “People might not agree, but they’ll get a clear sense of what she stands for.”

The Montessori Connection

Kripalani met Maria Montessori in the spring of 1946, during an intensive teacher-training course in Karachi, India. Before that, Kripalani had been teaching in her hometown for a few years. She says her methods were aligned with Montessori’s even before she knew about her. “She explained to me the philosophy that was always at the back of my work,” Kripalani says.

Kripalani and her family left the refugee camp in 1948, when she was asked to start a school in Bombay for the children of members of the Indian Army. There, her biggest challenge was integrating children from vastly different social classes who came from all parts of the country and spoke several different languages.

She accomplished this not with money or fancy teaching materials, but with the basic Montessori tenet: Respect every child. Kripalani began each student at a level they were comfortable with, and then guided each one individually to advance. To overcome class and cultural barriers, she gave all of the children the same uniform, and shared her lunch with all of them.

Tragedy hit in 1962, when Kripalani’s mother died in a kitchen fire. Kripalani was shattered, until her aunt gave her a copy of Time magazine with an article about the resurgence of Montessori education in the United States. She urged Kripalani to inquire about a job.

Within a year, Kripalani was on a plane — her first — to a teaching position in Iowa City, Iowa. But after two years of uneasy interactions at the school, she was desperate to leave the Midwest and accepted a teaching position in Newark. She has been in the Garden State ever since.

New Jersey Impact

In 1966, she received a master’s degree in education from Seton Hall. Later that year, she opened the Montes- sori Center of New Jersey in Montclair, which offered a one-year program for Montessori certification. The program was extremely rigorous, according to former students.

For example, one of Montessori’s major principles is learning by doing. To teach addition and subtraction, you might have students work with wooden rods, rather than write numbers on a paper. In that spirit, Kripalani would ask her teachers-in-training to play with and draw a picture of every classroom material.

“This kind of annoyed all of us, at first, because we were all adults,” says Dede Coogan Beardsley, who completed the program in 1975 and went on to found the Mapleton Montessori School in Boulder, Colo. “But it really does allow you to know the material better when you’re measuring it, studying it, and drawing it.”

The training center was located in a house with three stories: a ground floor with a simulated classroom, a second floor for the teachers-in-training, and an attic, where Kripalani slept.

“It was obvious that Montessori wasn’t just an interest in her life, it was the interest in her life,” says Judith Tara Aronson, who did the program around the same time as Coogan Beardsley and is now a preschool teacher at the World Community Education Center in Bedford, Va.

Above all else, Kripalani emphasized the empirical approach of Maria Montessori: Observe each student and see how he or she responds to different learning materials. ”She taught us not to memorize a recipe, but to think like a cook,” Aronson says.

Severe arthritis has slowed down Kripalani, the veteran teacher, but she’s still active in the Montessori community. Last year, she won the prestigious Lifetime Achievement Award from the American Montessori Society (AMS), and an honorary educator award from Montessorian World International. She regularly answers questions from teachers in online forums, and still travels by herself to Montessori events across the country.

“I always smile when I see Lakshmi at conferences sitting with a group of young teachers around her. She’s like a mother goose,” says Marie Dugan, an educational consultant for the AMS.

“The idea of sharing the information she has, it’s a strong part of her character and something she believes she’s meant to do,” Dugan says. A few years ago, Kripalani donated all of her meticulous notes and articles to the AMS archive at the Thomas J. Dodd Research Center at the University of Connecticut. ”It was such a precious gift to us,” Dugan says.

Kripalani has always set ambitious goals for herself, and has no plans to stop. “I have a dream to reach every child with a Montessori education. And, I don’t know, maybe that’s the reason I’m still living,” she says with a chuckle.

– Virginia Hughes is a science writer based in New York City.