Can you imagine what it would be like to only have one picture of your family? Or if your family only had one picture of you, and there was only one copy of it anywhere?

Can you imagine what it would be like to only have one picture of your family? Or if your family only had one picture of you, and there was only one copy of it anywhere?

Before photography was invented, the only way you might have an image of your loved ones was to have a picture painted or drawn, and even once photography was invented, it was a complicated and often expensive process.

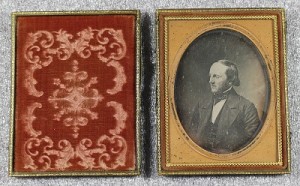

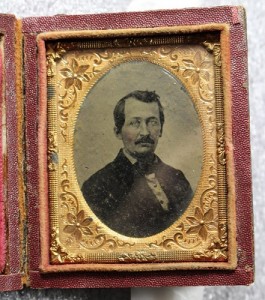

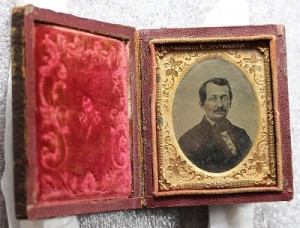

The daguerreotype (duh-GARE-oh-type) process was the first widespread photographic process. It was developed by Louis Daguerre in 1839. A piece of silver-plated copper was coated in light-sensitive chemicals, which created the photographic image when exposed to light in the camera. This piece of metal held the original image, which was very delicate and placed under glass for protection when viewing. In order to both protect the image and to add rich decoration to this precious object, the photograph was usually put into a decorative case. This case could be closed and carried around, or propped open on a shelf. But each image was unique, and couldn’t be reproduced without being photographed again.

Ambrotypes were created through a similar process, using glass coated in certain chemicals, then placed into decorative cases. The difference is that while a daguerreotype produced a positive image seen under glass, ambrotypes produced a negative image that became visible when the glass was backed by black material. In fact, this main difference is also the most reliable way to tell ambrotypes and daguerreotypes apart: daguerreotypes are backed by shiny silver, while ambrotypes are backed by a piece of glass painted black. The daguerreotype appears to be on a mirror, so when viewing it at an angle the dark areas are silver. For an ambrotype, the dark areas remain dark even at an angle.

Getting your picture taken was a special occasion, even for the well-off. People wore their very best outfits and jewelry. Because the process of exposing the chemicals to light could take a long time, people had to sit very, very still while the photograph was being taken. The solemnity of the occasion, and the need to sit very still, is why people sometimes look sad or uncomfortable in very old photographs. All photography was black-and-white until the end of the 19th century, but people often added some hand-painted color to brighten up the image. Very often, cheeks would be painted slightly pink, and buttons or jewelry would be painted gold. Adding color or decoration to the image, and placing it in a fancy case, emphasized the beauty, importance, or wealth of the person photographed.

In the Archdiocese of Newark photograph collection, we have a very few daguerreotypes and ambrotypes. The individuals in these images are not identified, but these photographs must have been precious to their families, which we know both from understanding the history of photography and the fact that these photographs survived to this day. Each of these images is unique, and was likely one of a very few, if not the only, photograph of these people their families may have had. We not only respect and care for these objects as fragile and delicate pieces of our history, but also for their beauty and for the people they so faithfully represent.

Interested in learning more? There are many resources on the history of photography on the web, including some that focus on daguerreotypes and similar processes. The Image Permanence Institute’s Graphic Atlas lets you compare and identify formats, or just explore fascinating images of different types. Daguerreobase includes a great deal of helpful information on identifying daguerreotypes as well as many beautiful examples. And for those who want to delve even further into the history of photography, this blog entry on Hunting and Gathering features e-book resources for you explore.