Son Of Sam

(Given the heavy subject matter, I thought I would offer a slight reprieve by compiling a playlist of the top 20 songs on the Billboard Hot 100 from the weeks of July 31, 1976 and August 6, 1977, which mark the beginning and the end of Son of Sam’s reign. Feel free to listen and get into the mindset of the time period!)

New Yorkers should have sensed that something terrible was brewing in the summer of 1976. It was as if the stars had aligned, and the universe was plotting against the city. Everything seemed to point to disaster. The top song on the Billboard Hot 100 was “Kiss and Say Goodbye” by The Manhattans.[1] The highest grossing movie at the box office was “The Omen.”[2] Even the charts were telling the city to beware.

Buhre Avenue is an unassuming street in the Pelham Bay neighborhood of the Bronx. Even as of 2022, it looks remarkably unchanged from the 1970s. One side of the street is composed of a series of brick rowhouses. The other houses a large apartment building, the Buhre Arms. All things considered, it’s a pretty typical snapshot of the Bronx. That is, of course, if you don’t take into consideration its sordid past. In the early morning hours of July 29, 1976, Donna Lauria and Jody Valenti sat in Jody’s car in front of the Buhre Arms building discussing the events of their evening.[3] The 18- and 19-year-old friends had no reason to be afraid. Donna lived right inside the building, they had just seen her parents walking back in after their own night out, and Jody’s house was nearby.[4] Pelham Bay was a low-crime, middle class neighborhood. It should have been safe, and it was, until Donna and Jody were shot at point-blank range by a stranger with a .44-caliber. Jody survived the shooting. Donna was killed immediately. No one knew it at the time, but the attack on the girls in Pelham Bay would become the beginning of the yearlong reign of terror of New York’s most infamous serial killer.

New York has never been a stranger to crime. With the city’s population inching closer and closer to 8 million as of the 1970 U.S. Census,[5] there was bound to be a healthy dose of civil unrest. Donna Lauria’s murder was one of over 1600 in 1976 alone.[6] The NYPD was exhausted and the investigation into Donna’s death brought forth no leads. It seemed for a while that she would be resigned to forever be just another nameless, faceless victim of the trademark violence of New York in the 70s.

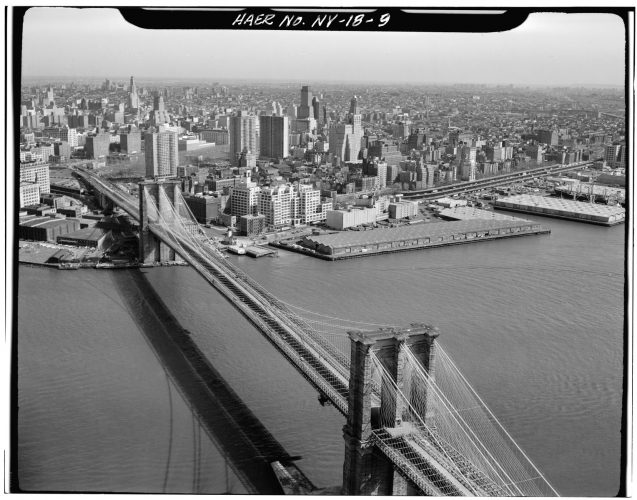

Aside from a few nonfatal shootings with no apparent connection, the rest of 1976 went by relatively smoothly. January 30, 1977, however, brought back chaos. Christine Freund and her fiancé John Diel were parked across the street from the Forest Hills Station in Queens. Forest Hills was known for its affluence, with the median household income significantly surpassing that of the rest of the city, and for its overwhelmingly white, Jewish population.[7] Today, the Forest Hills Station Plaza is beautiful. Overall, not a bad place to close out an evening, at least, that’s presumably what Christine and John thought until three .44-caliber bullets crashed through the window of John’s car, one of which lodged itself in Christine’s head.[8] The bullet to the head was ruled as her cause of death when she died as St. John’s Hospital several hours later.

It was at this point when connections began to form between the cases. A string of shootings, all with the same type of firearm, all aiming into the closed windows of parked cars, could hardly be a coincidence. Alarm bells sounded even louder on March 8, 1977, when 19-year-old Columbia University student Virginia Voskerichian was shot and killed on her walk home, only half a block from the site of Christine Freund’s murder less than two months earlier.[9] Police concluded that the same weapon killed both Christine and Virginia, leading them to believe that these killings were the work of a single person, who came to be known as “The .44-Caliber Killer.”[10]

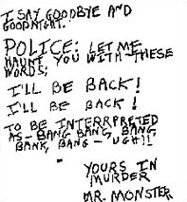

Public interest was piqued at the prospect of a serial killer in New York City, but absolutely exploded after the bodies of Valentina Suriani and Alexander Esau were found inside a car parked in front of 1878 Hutchinson River Parkway in the Bronx on April 17. Tucked inside the broken window, amongst broken glass and Valentina and Alexander’s blood, was a handwritten note addressed to the NYPD Captain, presumably left by the killer. He addressed himself as the “Son of Sam,” and the rambling note, riddled with misspellings, reads as the ravings of a madman. He taunted the police for not catching him and expressed intense desire to carry on his legacy. Once the note was released to the public and the new self-imposed nickname was adopted, New York began to truly live up to the nickname “the city that never sleeps.” The air became thick with the putrid scent of mortal terror. People began changing their routines to avoid the killer at all costs. No one went out after dark. No one walked the streets alone. And absolutely no one dared to sit around in a parked car. The risk was too great; Son of Sam was indiscriminately killing people, with no apparent preference or shared victimology. Anyone could be next. Upon the release of a composite sketch of the killer, minds began to wander. One Wall Street Journal article quoted a woman who admitted she sized up anyone on the subway who looked like they had the “right haircut.”[11] Every single newspaper and tabloid was printing article after article about the Son of Sam. Speculations about his identity and motive were varied and wide-reaching. Detectives operated under the assumption that he believed he was possessed by a demon, while psychologists pegged him as a paranoid schizophrenic.[12] The fascination with this mysterious figure grew by the hour.

The concept of media sensationalism is nothing new. Historian Joy Wiltenburg estimates that sensational reporting has its roots in the 16th century, despite the term “sensationalism” not appearing in the vernacular until the 1800s.[13] True crime, specifically, has always been subject to sensationalism. Morbid curiosity combined with the human compulsion for rational explanation is the perfect recipe for the relentless barrage of crime media coverage. Early in its history, crime media focused primarily on victims, giving little publicity to criminals themselves, but at some point, the lines between individual victims began to blur. They became interchangeable tropes and, after an initial spurt of pity from the public, they were thrust out of the public eye just as quickly as they had entered it. This was when media began to focus on the criminals, who provided a much more enthralling story. Victims were typically normal, everyday people. Criminals, more specifically, murderers, represented the epitome of human depravity.[14] They existed on the outskirts of societal norms and people were simultaneously disgusted and awed by their stories. This is why the Son of Sam craze came as no surprise. In 1977, he was New York’s biggest celebrity, and no one even knew who he was.[15] The speculation alone was enough to feed millions of New Yorkers hungry for juicy, heinous details.

What would become Son of Sam’s final killing occurred two days after the one-year anniversary of Donna Lauria’s death, on July 31, 1977. Twenty-year-olds Stacy Moskowitz and Robert Violante were kissing in Robert’s car after what was, apparently, a pretty good first date. They were parked on the corner of Shore Parkway and Bay 14th Street in Bath Beach, Brooklyn when several rounds were fired through the passenger window, one of which resulted in Stacy’s death.[16] The manhunt for the killer continued for another week and a half until police found a gun identical to the model that had killed all of Son of Sam’s victims in an illegally parked car not far from the scene of Stacy’s murder.[17] The car belonged to 24-year-old David Berkowitz, a short, boring, and frankly, unattractive postal worker. When confronted by police at his home in Yonkers, Berkowitz reportedly gave a slight smile before stating, simply, “Well, you got me.”[18]

The media coverage of the apprehension, trial, and subsequent conviction of David Berkowitz led to vehement debates about the ethics of journalism that still have relevance to this day. Given the scope of New York City’s influence and the richness of its journalistic history, it seems natural that the debate would originate within the confines of the five boroughs. Freedom of the press was called into question. Critics of tabloids’ handlings of the case questioned whether journalists were abusing their freedom and shirking certain civil responsibilities in favor of selling a story.[19] There continues to be a fine line between reporting the news and exploiting it. This is not just isolated to New York City, either. The media tendency to capitalize on crime has surged in a national capacity for decades following the Son of Sam murders. It begs the questions: What do we really want to know? The truth or the spectacle?

At the time of Berkowitz’s arrest, the two most popular New York City tabloids were The Daily News and The New York Post. The two newspapers were repeatedly accused of sensationalizing the crimes in order to increase their circulation, something editors vehemently denied. But the numbers speak for themselves. On an average news day, The Post sold around 600,000 copies and The News sold upwards of 1.5 million. On the day of Berkowitz’s arrest, circulation increased to 1 million for The Post and over 2 million for The News.[20]

The story of Son of Sam, his victims, and the city he held captive serve as a reminder to us, even 45 years later, of the capacity of humankind for cruelty. Whether that cruelty comes in the form of point-blank shots to the face or the exploitation of the deaths of six young people is up to the individual. But no matter how you slice it, the Son of Sam saga was one that transfixed the city of New York and created a unique and generational breed of fear, as well as an undying thirst for the knowledge of the most unspeakable acts of humankind.

[1] “The Hot 100.” Billboard. Billboard, March 18, 2022.

[2] “50 Top-Grossing Films.” Variety. July 28, 1976.

[3] Oppenheimer, Jerry. “Son of Sam Survivor Breaks Her Silence after 40 Years.” New York Post. New York Post, July 18, 2016.

[4] Oppenheimer, “Son of Sam Survivor.”

[5] U.S. Census Bureau; 1970 Second Count File B.

[6] Cooney, John E., Georgette Jasen, and Jonathan Kwitny. “’Son of Sam’ Creates Special Fear in a City Accustomed to Crime.” Wall Street Journal. August 10, 1977.

[7] Soffer, Jonathan M. “9 New York: Divided and Broke (1973-77).” Chapter. In Ed Koch and the Rebuilding of New York City, 105–20. New York, NY: Columbia University Press, 2012.

[8] Terry, Maury. The Ultimate Evil: The Truth about the Cult Murders: Son of Sam & Beyond. New York, NY: Bantam Books, 1989.

[9] McQuiston, John T. “Columbia Coed, 19, Is Slain on Street In Forest Hills.” The New York Times, March 9, 1977.

[10] Ivins, Molly. “Stalking a Man Called ‘Son of Sam,’ the .44-Caliber Killer.” New York Times, May 21, 1977.

[11]Cooney et al., “Special Fear.”

[12] Ivins, “Stalking ‘Son of Sam.’”

[13] Wiltenburg, Joy. “True Crime: The Origins of Modern Sensationalism.” The American Historical Review 109, no. 5 (December 2004): 1377–1404.

[14] Wiltenburg, “Modern Sensationalism.”

[15] Wiest, Julie B. Dissertation. Serial Killers as Heroes in the Media’s Storybook of Murder: A Textual Analysis of the New York Times Coverage of the “Son of Sam”, the “Boston Strangler”, and The “Night Stalker”, 2003.

[16] Sanyal, Pathikrit. “Neysa Moscowitz: Mother of David Berkowitz’s Last Victim Forgave Serial Killer ‘Son of Sam’, Here’s Why.” MEAWW, May 5, 2021.

[17] Moritz, Owen, Michael Oreskes, Albert Davila, and Patrick Doyle. “David Berkowitz Arrested for Son of Sam Killings after Biggest Manhunt in New York City History.” Daily News. August 11, 1977.

[18] Moritz et al., “David Berkowitz Arrested.”

[19] Winfrey, Carey. “’Son of Sam’ Case Poses Thorny Issues for Press.” The New York Times, August 22, 1977.

[20] Winfrey, “Thorny Issues.”

Bath Beach

After a pleasant first date on July 31, 1977, 20-year-olds Stacy Moskowitz and Robert Violante were closing out the night with some goodbye kisses in Robert’s car. Almost like clockwork, the elusive Son of Sam appeared, brandishing his famed .44 caliber, and shot through the passenger window. Both Stacy and Robert were shot in the ...

Forest Hills

On January 30, 1977 Christine Freund, 26, and her fiancé John Diel, 30, had just enjoyed an evening showing of Rocky and were sitting in John’s car planning the rest of their night when out of nowhere, a stranger fired a .44 caliber through the closed passenger-side window. Christine was shot in the head and, although ...

Hutchinson River Parkway

On a quiet service road on the Hutchinson River Parkway in the Bronx, Valentina Suriani, 18, and Alexander Esau, 20, were sitting in Alexander’s brother’s car, only a block away from Valentina’s house. They were confronted by an armed man on the evening of April 17, 1977, when both were fatally shot. Valentina died instantly ...

Pelham Bay

In the 1970s, the Pelham Bay neighborhood of the Bronx was a low-crime, middle-class area of the city. It wasn’t until 18-year-old Donna Lauria and 19-year-old Jody Valenti were shot through the closed passenger window of Jody’s car while parked outside of Donna’s building, the Buhre Arms, that there was any reason to be afraid. ...

Son Of Sam

Son Of Sam (Given the heavy subject matter, I thought I would offer a slight reprieve by compiling a playlist of the top 20 songs on the Billboard Hot 100 from the weeks of July 31, 1976 and August 6, 1977, which mark the ...