In the 1930s, Italian immigrants emigrated to the United States in large numbers, and especially settled in New York City. Most of these immigrants, from Southern Italy, suffered crushing poverty and a lack of industrialization following Italian Unification in the 1860s. After economically and socially being left behind, in desperation, Southern Italian immigrants emigrated to the Western hemisphere, and of those who emigrated to the United States and made new homes in New York City, many faced nativist sentiments pushing immigrants and next generation Italian-Americans towards assimilation. While some believed that the New York organized crime scene was a sign of assimilation, the actual structure of this crime organization borrowed heavily from Southern Italian organized crime. The condemnation by assimilated Italian-Americans of future generations also supported this sentiment, and by extension, the New York mafia seemed more a relic of the old country and a method of resistance against full assimilation as opposed to the conceived notion that it was a sign of adaption into the larger New York and American culture; essentially, like the mutual aid societies of the 1930s, New York City organized crime functioned as a survival tactic for navigation in the United States while still retaining Italian culture for these immigrants and first-generation Americans.[1]

For a better sense of how Italian-American New York City organized crime operated, comparing the Southern Italian mafia to its counterpart was enlightening. As a 1931 article in the New York Times explained, “The Mafia organization obtained its start in Sicily and the Naples region as a result of bad government and lawlessness under Bourbon kings more than a century ago, and especially during the Napoleonic invasion of Italy.”[2] In this respect, due to Bourbon kings neglecting and abandoning the Southern region of the peninsula and respective islands, Southern Italy sustained a power vacuum due to a lack of order; in the void emerged a group of people ready to step in and demand structure. In New York City, as in Southern Italy, recent immigrants experienced a lack of order and confronted shabby living conditions due to economic plight. However, while the mafia in Southern Italy operated similarly to its New York City counterpart, Americans feared the immigrant offspring might find, in some ways, more success. Another New York Times article, written in 1907, asserted, “Italians colonize in tenement districts, and there maintain “Little Italies” in which the criminally skillful wield a power never exercised on the Peninsula or in Sicily,” and went on to argue, “American Italian colonies thus become fruitful fields of operation for those intelligent Italian criminals who over here are more or less free from police surveillance.”[3] This article represented many concerns New Yorkers held, aligning with national nativist paranoia about whether or not Italian immigrants would or even could become “fully American” with these survival strategies in use. Regardless of adaptability, these articles, as demonstrated throughout three decades, held a consistent xenophobic worry of the potency and power of Italian organized crime. However, organized crime was not the only group method of navigating through the United States for these immigrants.

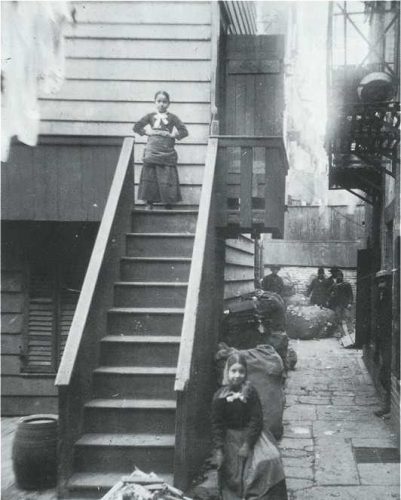

While many families struggled to survive due to work instability, unsafe job environments, unhealthy living conditions in tenements throughout New York City, and a lack of structural support, members from within families opted to create order where it no longer existed. Additionally, external groups formed to facilitate another means of support; however, this aid arose from immigrants adapting for survival, guided and influenced by a historical presence and precedence of organized crime in Southern Italy. Throughout family units, Italian immigrant women in New York City became chief networkers while, in other arenas, some men struggling to survive turned towards organized crime in the Four Points. Many Italian immigrant women in clustered family units banded together to create social networks and establish order, “relying heavily on the networks of mutual support and reciprocity with those who lived closest to them, whether kin or neighbors.”[4] Guglielmo demonstrated the need for ethnic communities to support each other, a reality which applied to more than just Italian immigrants. Because the United States did not offer many resources to help new immigrants, and these Italian immigrants felt isolated in a new country, they often worked together for survival and structure, especially through mutual aid societies. However, family networks were not the only unit extending a seemingly helpful hand to Italian immigrants.

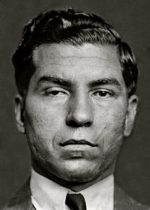

Italian crime organizations in New York City and other famous cities such as Chicago also attempted to help Italian immigrants traverse through the country. Al Capone, a New York-born gang leader who operated in Chicago, represented the duality of media coverages toward crime-associated Italians. As a New York Times article assessed, he held both the image of a ruthlessly violent criminal and a joyously laugh-filled father and husband. Additionally, many street sources echoed the rumors that Capone “spent thousands to feed the unemployed [ . . . ] how he provided shelter for them on particularly bitter nights in tenements he owns.”[5] This philanthropic side to Al Capone, who many in the United States feared, while not an excuse or justification for his actions, demonstrated that his role in organized crime did not exclusively harm others, as many Americans feared. In fact, his history of assisting others through organized crime did not solely manifest through philanthropy; Al Capone also worked to help his community. While in Brooklyn, “At 14, he formed the Navy Street Gang to put an end to harassment of Italian women and girls by their Irish neighbors.”[6] In this passage, he deliberately took on a role akin to that of the Southern Italian mafia, specifically in protecting those in his community. Despite being a child, he too noticed an absence of order, and when he realized nobody acted to restore it, he took actions into his own hands: he sought to protect the women in his community from harassment. This specific example also aligned similarly to the folk tale or legend of the Sicilian mafia’s origins, which described its inception as arising from a need to protect a Sicilian woman from adversary troops’ advancements and aggressive sexual contact with locals.

In fact, the image of Italian organized crime in New York City, as perceived by Americans throughout the United States, worked as a means to spread xenophobic nativist sentiment against Southern Italian immigrants. The legacy of this narrative still manifested five decades later, in the late 1980s during a trial in which, “actors were engaged by the court to read transcripts because the defendants’ Sicilian dialect was not understood by the jury. In turn, real gangsters began to fulfill the television and film stereotypes.”[7] This passage left a lot to unpack, but most prevalent was a sense of foreignness to this Sicilian defendant. To start, the fact the jury did not understand him represented a lack of Americanization because he maintained Sicilian in the courtroom. Likewise, the quote also demonstrated a confirmation bias, in which public perception of gangsters ultimately caused said gangsters to meet expectations in a seemingly cause-effect relationship. Much like the New York Times newspaper articles from the early 1900s which blatantly and unapologetically argued Italian immigrants exhibited undesirable traits that needed to be “Americanized” out of them, media attention throughout the 1900s heavily shaped social conceptions of Italian immigrants throughout the United States.[8] These sentiments demonstrated not just an aversion to immigrants or to organized crime as separately exclusive concepts, but instead the notion of Americans feeling threatened by the lack of a homogeneous culture, language, and identity. The larger American culture’s rejection of a person’s language and personal life via anecdotes enough for newspaper articles to tout a need to Americanize certain attitudes out of a person demonstrated an insecurity of an American character; this insecurity most blatantly manifested in relation to the New York organized crime scene, wherein American-born citizens painted Italian immigrants as seemingly the sole, or main perpetrators and masterminds of these organizations. In this respect, nativist rallying cries bludgeoned Southern Italian immigrants’ connection with their heritage in New York City and throughout the United States, despite the fact perpetrators of this notion conflated everyday Italian immigrants with the criminals they feared.

Italian American immigrants in New York City struggled in unsafe and unhealthy living conditions. For survival, these immigrants turned towards community methods of social security, often through mutual aid societies and women-led networks of families. However, some turned towards organized crime, which so visibly mimicked the Southern Italian mafia enough to disqualify it as a point of “Americanization.” Instead, this community served as one of many survival tactics and resources to navigate and exist in the United States, and especially in New York City. While violence certainly caused harm across different cities and throughout various communities, Italian-American organized crime also brought benefits to recent Italian immigrants and American-born descendants of Italians in New York City.

Notes:

[1] May, Vanessa. “”New” Immigrants.” Lecture, Class at Seton Hall University, South Orange, NJ, February 3, 2020.

[2] “Mafia Is Further Weakened by Many New Convictions: Trials in Sicily Are a Part of a Long Campaign to Put an End to a System of Terrorism Germany’s Middle Class Shows Reduced Earnings.,” New York Times, June 28, 1931.

[3] “The Italian Immigrant,” New York Times (1857-1922), Apr 22, 1907.

[4] Jennifer Guglielmo, Living the Revolution: Italian Women’s Resistance and Radicalism in New York City, 1880-1945. Gender and American Culture. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2012, 118.

[5] Meyer Berger. Associated Press Photo. “Al Capone Now Emerges in a New Personality: a Smiling Capone.” New York Times, Oct 18, 1931.

[6] Luciano J. Iorizzo Al Capone : A Biography, Greenwood Biographies. Greenwood Press, 2003, 24.

[7] Jerry Mangione, and Ben Morreale, La Storia : Five Centuries of the Italian American Experience 1St HarperPerennial ed. New York, New York: HarperPerennial, 1983, 349.

[8] “Characteristics of Italian Immigrants.,” New York Times, May 18, 1902.