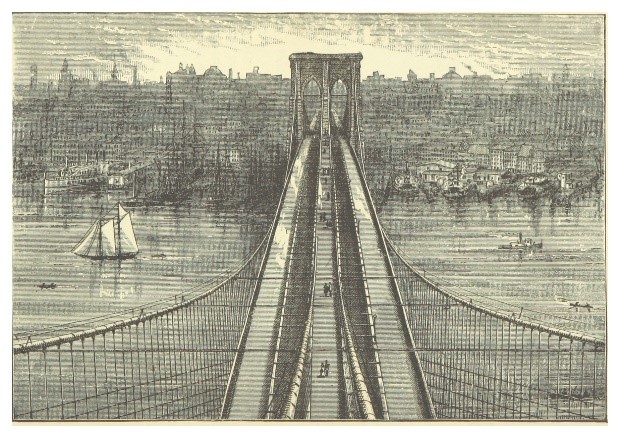

In a New York Times article titled “Celebrating the Brooklyn Bridge” published in 1983, Manuel T. Murica writes that “[t]he bridge served as a backdrop for all of [his] daily activities during [his] childhood.”[1] Murica played baseball under the bridge, jogged every morning, walked many evenings, and shared a stroll on the bridge with his first girlfriend. From an individual perspective, Murica’s experiences with the Brooklyn Bridge are irreplaceable. His perspective of the bridge speaks the unique effect it has on many New York citizens. Murica’s language such as “backdrop” emphasizes that the bridge is ever present and intimately involved with many individuals’ lives. Growing up with the Brooklyn Bridge is a symbol of pride. However, Murica’s celebration of the bridge is not unique to the eighties or the modern era; the bridge has been celebrated since before its opening on May 24, 1883. For example, there were months of preparation for the grand opening of the bridge involving fireworks, commemoration speeches, and invitations to “the President, Vice-Presidents, and ex-Presidents of the United States” Cabinet members, governors, and foreign ambassadors.[2] The opening ceremony for the bridge was driven to have as many “distinguished citizens” from across the country as possible.[3] Since before the bridge’s opening, it has been surrounded in excitement, awe, and recognition as a New York landmark. The invitation of national public figures and foreign ambassadors underscores that the bridge’s opening as a national event. Measuring at sixteen thousand feet long and two hundred seventy-six feet tall, the Brooklyn Bridge was the largest suspension bridge in the world in 1883. The bridge was seven times taller than another structure in New York. John Roebling, the bridge’s designer, and first chief engineer, designed the bridge to be a technological marvel. According to Robert Begley in his essay “The Brooklyn Bridge: A Monument to the Human Spirit,” persisting into 2018, the Brooklyn Bridge symbolizes “heroism and innovation.”[4] The massive size of the bridge and its design centered around the use of four main cables gave reason to celebrate the bridge from a technological standpoint. In addition, workers risked their lives building the bridge in the highly pressurized caissons that allowed the construction of the bridge’s foundation. John Roebling’s son William Roebling fell ill as a result of such dangerous working conditions. As a result of the dangerous nature of building the bridge, the worker’s heroism is celebrated with the bridge. Regardless of function, the mere existence of the Brooklyn Bridge continues to be celebrated today as when it was opened in 1883.

In addition to connecting Manhattan and Brooklyn, the Brooklyn Bridge has served as a point of various forms of connection. For example, four years after the bridge’s opening in an article from 1887 of the New York Times, a writer comments that the “scene daily witnessed by those who ride across the Brooklyn Bridge between 5 and 7…cannot be duplicated elsewhere.”[5] The writer is referring to the conflict between passengers attempting to ride over the Brooklyn Bridge. People would shove, throw elbows, and anchor themselves in other peoples’ paths in order to claim a seat on that railway, similar to how people act on the modern subways. While the writer’s comments may seem to suggest division amongst citizens as a result of the bridge, he or she continues to write that if anyone had ideas to solve such a conflict over seating that they had “no right to keep it secret”[6] Language such as “no right” implies that there is a communal responsibility to maintain and improve the condition of the bridge and its “patrons.” The bridge creates a value of a singular community. Furthermore, the same writer insists that taking care of the bridge is “[t]he greatest good for the greatest number.”[7] The writer is making use of utilitarian philosophy to rally commitment to maintaining the bridge. In addition to a communal point of connection, the bridge also takes on a philosophical connection. Hart Crane, in his epic poem The Bridge addressing the Brooklyn Bridge and inspired by the bridge, notes that “[o]ut of some subway scuttle, cell or loft / [a] bedlamite speeds to thy parapets”[8] The word “bedlamite” refers to someone who is a social outcast. The bridge, according to Crane, collapses social classes by drawing all classes to it. Moreover, the phrase “cell or loft” reinforces the value the bridge is not exclusively for the wealthy or working class, but for all people. Beyond a communal connection, the bridge also connects different periods in time. For instance, Hart Crane writes that through “[b]eading thy path condense eternity.”[9] The bridge continuing to be in use today acts as a daily ritual that connects the modern era with the past. Moreover, the sheer height of the bridge in comparison to the rest of New York when it was initially built foreshadowed the towering modern New York skyline. The bridge serves as a connection of surrounding communities, social classes, literary history, and the present with the past. As Begley asserts, “[n]o visit to New York is complete until you’ve walked across this engineering marvel.”[10] The continued celebration and use of the Brooklyn Bridge allows spectators to connect with the history of New York.

However, the Brooklyn Bridge was not unanimously celebrated as there were several protests towards its construction concerned that the bridge would ruin the economy. For example, in the “Letters to the Editor” column of the New York Times an anonymous writer criticized the bridge as overly expensive, its costs continuously rose, connecting Manhattan and Brooklyn was useless, and the project as a whole was infeasible.[11] Many of the critics of the project were merchants and real-estate owners who feared that the bridge would harm trade of the East River ports. Protestors feared that the bridge would obstruct navigation along the East River. The anxieties surrounding the bridge were the same fears of nearly every technological innovation such as a fear that it won’t work, is a danger to public safety, and is harmful to existing jobs as well as the economy. However, as people adjust to new technology, like the Brooklyn Bridge, its use becomes commonplace. For example, the first day the bridge opened around fifteen thousand people crossed, but now one hundred twenty thousand vehicles and four thousand pedestrians cross daily.[12] While protest to the bridge was in the minority, resistance to it may have persisted because of the Puck magazine. Puck magazine was a satirical publication that mocked, for the sake of humor, the news. Patricia Marks in her essay “What Builders These Mortals Be: Puck’s View of the Brooklyn Bridge” notes that through the use of graphics, journalists pointed to the “dubious quality of the materials and the resulting dangers of its construction.”[13] Through challenging the qualities of the materials and dangers of construction, Puck magazine attempted to undercut the view that the bridge was a technological marvel. To some extent, the satirical magazine was successful in spreading doubt as people increasingly feared the bridge could not support a lot of weight. While the weight concerns over the bridge were ultimately unfounded, the magazine’s efforts underscore the strength of media to influence public concern in light of public protests.

The Brooklyn Bridge’s connection to the corruption of Boss Tweed and Tammany Hall supported existing resistance to its use. For example, in a New York Times article reporting the interrogation of Boss Tweed the Prosecutor noted “$65,000 were paid to certain Aldermen to induce them to appropriate $1,500,000 toward the Brooklyn Bridge.”[14] Boss Tweed was on the executive committee that approved the construction of the bridge. Although Boss Tweed pushed for the construction of many infrastructure improvements, he was notorious for paying workers to inflate bills so he and his partners could take a profit. The Prosecutor’s question of the $1,500,000 bill for $65,000 of work, regardless of truth, in part sullied the public’s view of the bridge. The Brooklyn Bridge seemed to have been one of Boss Tweed’s project in which he stole public funding. Furthermore, the Prosecutor noted that during construction there were issues of poor-quality materials which Tweed purposed a solution to solve.[15] The Prosecutor’s questioning takes advantage of Tweed’s corrupt reputation by connecting him with poor materials regardless of what Tweed purposed to solve the issue. As a result, doubt over the safety of the bridge continued to spread. Ironically, while Tweed was the driving force to get the bridge’s construction approved, its connection to him hurt the public opinion of the project.

Although the construction of the Brooklyn Bridge created some conflict among New Yorkers, such conflict created a point of contact between differing political, social, and economic groups. Opposing groups were encouraged to engage with each others’ viewpoints. Some viewed the bridge as an economic gain, while others believed it would harm trade. Tammany Hall had to engage with anti-Tammany sentiment. People of differing social classes had a singular place to take pride in together. The Brooklyn Bridge helped close many gaps between the various New York identities to create a more solidified, sometimes conflicting, New Yorker identity.

[1] Manuel T. Murica, “Celebrating the Brooklyn Bridge,” New York Times, May 1, 1983, SM94.

[2] “The Brooklyn Bridge,” New York Times, Apr. 19, 1883, 8.

[3] Ibid., 2.

[4] Robert Begley, “The Brooklyn Bridge: A Monument to the Human Spirit,” The Objective Standard (2018): 113-115.

[5] “The Brooklyn Bridge,” New York Times, Oct. 31, 1887, 4.

[6] Ibid.,2.

[7] Ibid.,3.

[8] Hart Crane. “To Brooklyn Bridge,” Anthology of American Literature, 11th Volume, 10th Edition (New York: Longman, 2001), 1413-1414.

[9] Ibid.,2.

[10] Robert Begley, “The Brooklyn Bridge: A Monument to the Human Spirit,” The Objective Standard (2018): 113-115.

[11] Flatbush, “Letters to the Editor: The Brooklyn Bridge,” New York Times, Jul. 16, 1881, 3.

[12] Robert Begley, “The Brooklyn Bridge: A Monument to the Human Spirit,” The Objective Standard (2018): 113-115.

[13] Patricia Marks “What Builders These Mortals Be: Puck’s View of the Brooklyn Bridge,” American Periodicals 29 (2019): 43–62.

[14] “Mr. Tweed and His Tales: The Examination Continued,” New York Times, Oct. 7, 1877, 1.

[15] Ibid.,2.

“Measuring at sixteen thousand feet long and two hundred seventy-six feet tall, the Brooklyn Bridge was the largest suspension bridge in the world in 1883. ”

“Sixteen thousand feet long?” Try sixteen hundred feet for the main span.

If it were three miles long it would go all the way across Manhattan.