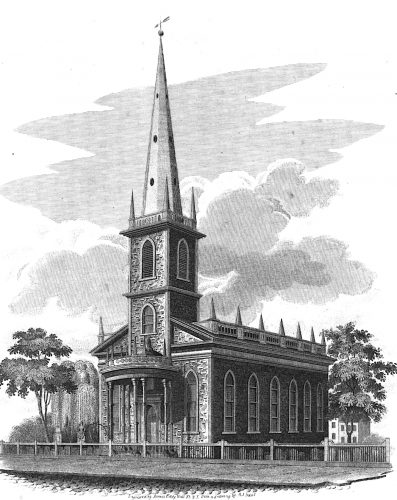

The last stop on this tour of Revolutionary New York is Trinity Church. The current building is not the same one that stood during the Revolutionary period, as it burned down in a fire in 1776. Trinity was an Episcopal church whose steeple was an important feature of the city’s skyline, standing at 175 feet.[1] It was one of the many churches that could be found in New York City. New York was a very diverse place in many different aspects, one of which was religion. There were groups from all over that came to New York and groups often worshiped at their own churches. Religion in New York also showed class divides. Society’s upper classes attended services at Trinity. Members included government officials, wealthy merchants, and landlords, such as members of the DeLancey family. This made Anglicanism a powerful force in society. Describing the church on a Sunday, one observer stated, “‘I counted 13 coaches and chariots waiting at the door of this church for their owners, and in truth the number of Equipages in this town, considering the extent of it, is surprising, and most of them exceeding fine ones too.’”[2] It is clear from this account that wealthier New Yorkers were the ones attending services at Trinity Church, which can be gathered based on the quantity and quality of carriages by the church. The very wealthy would be the only ones able to afford these forms of transportation. Though many in the upper classes of society attended church at Trinity, not all did. Some families, such as the Livingstons, went to the Presbyterian Church. It is significant to note that once allegiances solidified, the families were on opposing sides, the DeLanceys remaining loyal to the crown, while the Livingstons became patriots.

Tragedy struck the church in September, 1776, when a fire broke out and spread uptown, engulfing many buildings in flames. About one-fourth of all the buildings in town were destroyed—including the church.[3] The loyalists blamed the patriots for the fire, but it was never verified who the true culprit was. A rector of Trinity Church, Charles Inglis, was a staunch supporter of the crown and his opinion was no different. “Alas!” he wrote, “the Enemies of Peace were secretly lurking among us. Several Rebels secreted themselves in the House to execute the diabolical Purpose of destroying the City.”[4] Inglis clearly has a low view of the rebels, calling their actions evil and associated with the devil. Another viewer, Philadelphia loyalist, Charles Stedman, goes as far as to state that the rebels “gave three cheers when the steeple of the old English church fell down, which, when burning, looked awfully grand.”[5] According to Stedman, not only were the rebels responsible for what he saw as a travesty, but they took pride in these actions—the destruction gratified them. It is interesting how he ends by saying it looked grand. The steeple of Trinity Church was one of the tallest structures in the city and to see it topple down would have been a sight indeed. These comments by Inglis and Stedman show a divide between patriots and loyalists throughout the city and the colonies: the patriot mob was causing destruction and disrupting the harmony of the city. The church was rebuilt after the war and is now an important place of worship as well as tourist site in the city, where visitors can also see the graveyard, which is the final resting place of prominent revolutionary New Yorkers, such as Alexander Hamilton and Horatio Gates.

Charles Inglis was a rector at Trinity Church. He remained loyal to the crown throughout the war and evacuated the city in November 1783 upon the departure of the British troops.

[1] Joseph S. Tiedemann, Reluctant Revolutionaries: New York City and the Road to Independence, 1763-1776 (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1997), 20.

[2] Robert Honeyman, Colonial Panorama 1775: Dr. Honeyman’s Journal for March and April, quoted in Joseph S. Tiedemann, Reluctant Revolutionaries: New York City and the Road to Independence, 1763-1776 (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1997), 20.

[3] Jill Lepore, New York Burning: Liberty Slavery, and Conspiracy in Eighteenth-Century Manhattan (New York: Vintage Books, 2005), 225.

[4] Charles Inglis, “Life and Letters of Charles Inglis,” October 31, 1776, in The Price of Loyalty: Tory Writings from the Revolutionary Era, ed. Catherine S. Crary (New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company, 1973), 168.

[5] Charles Stedman, “History of the Origin, Progress, and Termination of the American War,” 1792, in The Price of Loyalty: Tory Writings from the Revolutionary Era, ed. Catherine S. Crary (New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company, 1973), 167.

*Photos: A.J. Davis (artist) and James Eddy (engraver), “Trinity Church, N. Y. Drawn and Engraved for the New-York Mirror,” engraving, 1827, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Second_Trinity_Church_(Manhattan).jpg (accessed December 12, 2016).

![]()

Image found in Martha J. Lamb’s book Wall Street in History, “The Right Reverend Charles Inglis, D.D. The First Protestant Bishop in the British Colonies Consecrated for the See of Nova Scotia, 1787,” 1787, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:43THE_RIGHT_REVEREND_CHARLES_INGLIS.jpg (Accessed December 12, 2016).

![]()

“…it burned down in a fire in 1776. Trinity was an Episcopal church”

The Episcopal Church came into being, separate from the Church of England in 1789.