The long trad ition of common prayer in the monasteries of western Europe is based on the recitation of the 150 psalms at precise times of the day over the course of the week. The times for morning and early evening prayer drew upon the Jewish tradition for people to unite their intentions with the times when sacrifices were offered in the Temple. After the Temple was destroyed, this Jewish use of psalms and other prayers each day became “the sacrifice of the lips.” In this way the Pharisee tradition continued the practice of linking the time of prayer to the time of the Temple service.

ition of common prayer in the monasteries of western Europe is based on the recitation of the 150 psalms at precise times of the day over the course of the week. The times for morning and early evening prayer drew upon the Jewish tradition for people to unite their intentions with the times when sacrifices were offered in the Temple. After the Temple was destroyed, this Jewish use of psalms and other prayers each day became “the sacrifice of the lips.” In this way the Pharisee tradition continued the practice of linking the time of prayer to the time of the Temple service.

In the Church the reference in Psalm 119:164 (“Seven times a day I praise you because your edicts are just”) became the ideal for the monks to decide the number of the “hours,” i.e., the times for daily prayer, in addition to the celebration of the Eucharistic sacrifice.

Over the centuries the Church of the Roman rite introduced Latin hymns to introduce each of the “Hours.” After the Second Vatican Council the Hours may be celebrated in the vernacular language. Some hymns have been translated into English but a wide selection of more modern hymns in English allow for choices on the part of each community.

The Rev. Fred Pratt Green (1903-2000) was a British Methodist minister who wrote many hymns. The one I’ve chosen is assigned to Vespers or Evening Prayer in the Catholic Divine Office but it would be appropriate for morning as well. Here are three stanzas of this prayer:

For the fruits of his creation,

Thanks be to God;

For the gifts of every nation,

Thanks be to God;

For the ploughing, sowing, reaping,

Silent growth while men are sleeping,

Future needs in earth’s safekeeping,

Thanks be to God.

In the just reward of labor,

God’s will be done;

In the help we give our neighbor,

God’s will is done;

In our world-wise task of caring

For the hungry and despairing,

In the harvests men are sharing,

God’s will is done.

For the harvests of his spirit,

Thanks be to God;

For the good all men inherit,

Thanks be to God;

For the wonders that astound us,

For the truths that still confound us,

Most of all, that love has found us,

Thanks be to God.

Human industry and ingenuity have enhanced the productivity of God’s creation, a responsibility in the human vocation (Genesis 1:26-28; 2:15). Farmers use the machines of several inventors to increase the produce of areas that are cultivated. The phrase “Silent growth while men are sleeping” points to the parable of Mark 4:26-29:

26 And He was saying, “The kingdom of God is like a man who casts seed upon the soil; 27 and he goes to bed at night and gets up daily, and the seed sprouts and grows—how, he himself does not know. 28 The soil produces crops by itself; first the stalk, then the head, then the mature grain in the head. 29 And when the grain is ripe, he immediately puts in the sickle, because the harvest has come.” (New American Bible)

A century ago, scientists developed a type of wheat that could come to harvest within three months, the short growing season in western Canada. Rotation of crops has led to increased and varied productivity. For these contributions of human ingenuity we are grateful! Are the products of the fields reaching those who are hungry? The work of farmers must be channeled to places of great need.

Gratitude to God in the first stanza is balanced by the emphasis on human labor in the second. Workers in the field or vineyard deserve a living wage. Justice for the worker is an expression of God’s will, already emphasized in the Torah, especially in the Book of Deuteronomy.

Farmers realize the importance of good relations with their neighbors. An old farmer once told me of a situation of misunderstanding with his neighbor that had perdured for some time. While he was away a fire in his barn was extinguished by the neighbor. In gratitude, he overcame the problem that had caused tension. “We can choose our friends from afar but we must cultivate a true friendship with our neighbors.”

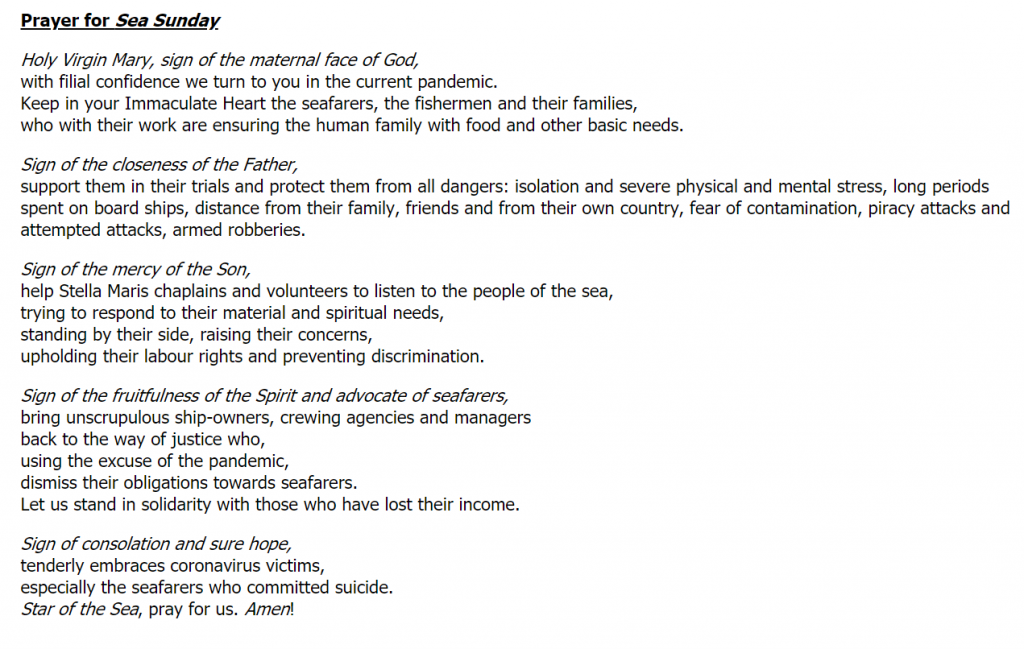

The poet’s focus moves to the human needs in far-off places – these involve the corporal and spiritual acts of mercy: “the hungry and despairing.” There are but one example in each category.

Lists of Jewish Sources

- Feed the hungry and give drink to the thirsty

- Clothe the naked

- Visit the sick

- Bury the dead and comfort the mourners

- Redeem the captive

- Educate the orphan and shelter the homeless

- Provide dowries for poor maidens

Spiritual works of mercy complement the list of “corporal works” given in Matthew 25:31-46

- Instruct the ignorant

- Counsel the doubtful

- Admonish sinners (see Matthew 18:15)

- Bear wrongs patiently (see Matthew 6:14)

- Forgive offenses

- Comfort the afflicted

- Pray for the living and the dead.

Share the abundance of the harvest with those who are less fortunate. Laws of Deut 15:7-11 exemplify care for the poor which offer guidance for modern communities.

The final stanza of Pratt Green’s poem draws attention to the benefits of the spiritual order.

“The good that all men inherit”- private property is a right limited by the call to advance the common good, which should be a heritage shared by all.

Wonder is an act of appreciation for the beautiful surprises of life. “The wonders that astound us” provoke a sense of awe on the part of creatures living in the presence of God.

“The truths that still confound us” – we examine our conscience with regard to limitations that we in a society place on relationships, beginning with God and embracing neighbor as an equal to self and extending to the natural world at large.

“Love has found us” – the love of God transforms our lives even before we begin to realize the multitude of gifts that are signs of God’s loving presence.

Another hymn taken into the Divine Office that celebrates the human response to divine blessings is by Isaac Watts (1674-1748), a Nonconformist hymnwriter who was the pastor of the Independent Congregation, Mark Lane in London from 1702-1712. Frail health dogged him for many years, but he produced texts that resonate well, even today for people with a poetic sense.

I sing the mighty power of God,

that made the mountains rise,

That spread the flowing seas abroad,

and built the lofty skies.

I sing the wisdom that ordained

the sun to rule the day;

The moon shines full at God’s command,

and all the stars obey.

I sing the goodness of the Lord,

who filled the earth with food,

Who formed the creatures through the Word,

and then pronounced them good.

Lord, how Thy wonders are displayed,

where’er I turn my eye,

If I survey the ground I tread,

or gaze upon the sky.

There’s not a plant or flower below,

but makes Thy glories known,

And clouds arise, and tempests blow,

by order from Thy throne;

While all that borrows life from Thee

is ever in Thy care;

And everywhere that we can be,

Thou, God art present there.

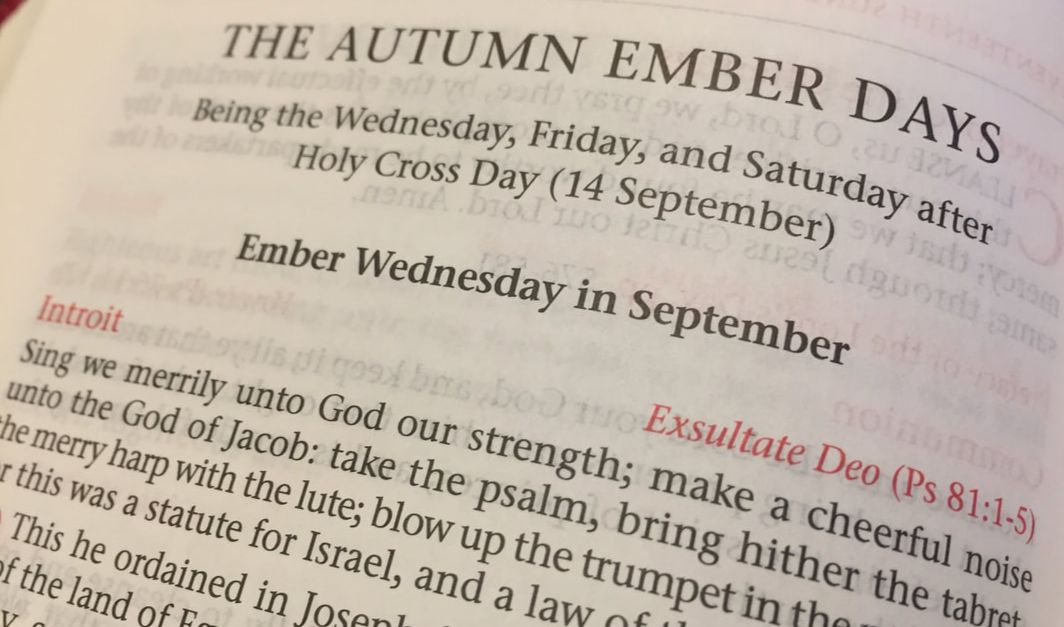

During a discussion among medievalists on prayer, I mentioned the ember days in the Church’s liturgy. Middle-aged participants asked: “What are ember days?”

During a discussion among medievalists on prayer, I mentioned the ember days in the Church’s liturgy. Middle-aged participants asked: “What are ember days?”