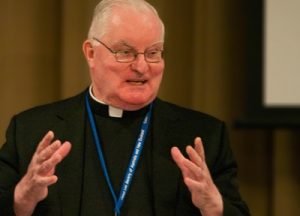

The death of my classmate, Father Francis Morrisey, on May 23, 2020 in Ottawa brings a stellar servant of the Gospel to the completion of a priestly ministry with an impact on the universal Church.

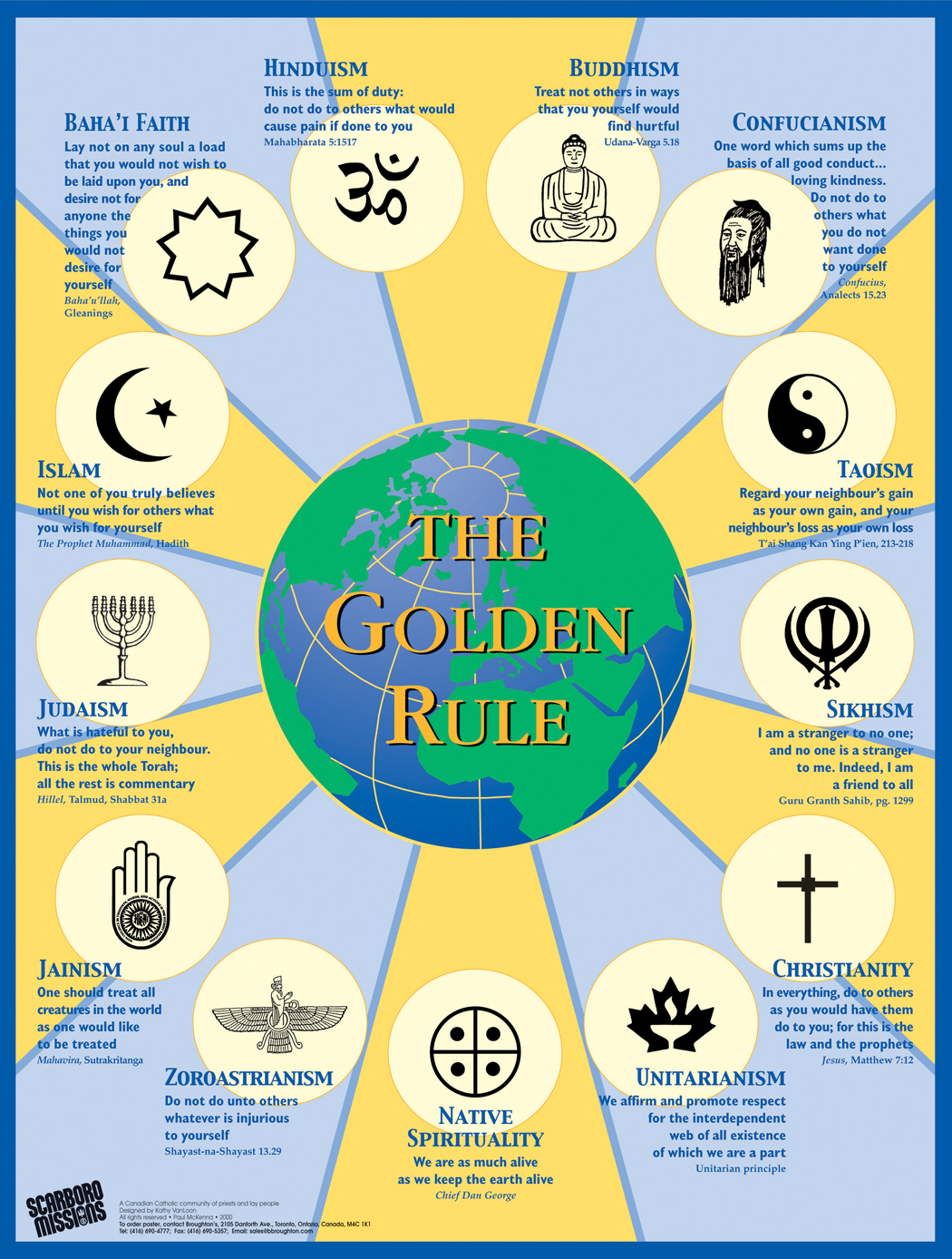

From 1958-62 we studied theology and related subjects at St. Paul’s Seminary in Ottawa. As an Oblate of Mary Immaculate in the French province, Frank was a scholastic while I was a seminarian for the diocesan priesthood. He was always a cheery presence in the breaks between class. He went on to study Canon Law in a faculty that included great professors like Father Germain Lesage, OMI. Frank and I studied the 1917 Codex Juris Canonici, promulgated by Pope Benedict XV. In the preface to this Code, Cardinal Gaspari declared that it would endure until the end of time! However, Pope John XXIII convoked a commission to revise the Code; Father Morrissey was a contributor to this work that was promulgated in 1983. The vision of the Church as People of God in the New Covenant permeates the vision of the Law at the service of the faithful. The work of interpreting and applying the Gospel in delicate situations of tension within the Church and the wider society occupied Frank’s attention for the rest of his life.

“In recognition of his generous use of…expertise on behalf of health care professionals in the U.S., Canada and the world,” Fr. Morrisey received Catholic Health Association’s (CHA) Lifetime Achievement Award on June 10, 2019. CHA commemorated this honor with the video below:

On May 6, 2020, Saint Paul University awarded Fr. Morrisey the Eugène de Mazenod Medal. This medal honours individuals who have made significant contributions to make their community, their environment and society as a whole more just and humane.

“The Church has been enriched by Frank’s selfless outpouring and, through the Church, cultures and societies throughout the world have also been enriched,” noted Monsignor John Renken, Dean of the Faculty of Canon Law at Saint Paul University. “He was esteemed and admired by a plethora of social innovators, church leaders and professional colleagues. He showed himself to be a faithful son of Saint Eugène de Mazenod, who envisioned bringing healing and hope to the peripheries of his own day. Frank has done the same in today’s world.” From St. Paul’s University (Ottawa, Canada) Reflection on Fr. Francis Morrisey

We pray for the happy repose of Father Morrisey’s soul, with the hope that he has been welcomed already into the Kingdom as a good and faithful servant!