Engaging, and Disengaging, on Xinjiang

The ongoing visit of UN undersecretary general for counterterrorism Vladimir Voronkov to China’s Xinjiang region, and the invitation to UN High Commissioner on Human Rights Michelle Bachelet to visit the region raise fresh questions on how best to approach the internment of one to two million Muslims in the region. While Beijing argues that it is providing job training to this religious minority and that its heavy securitization of the region is driven by terrorism concerns, satellite evidence and reports from eyewitnesses suggest that Beijing is systematically repressing the culture and religion of this minority through widespread surveillance and detentions.

Western governments, including the United States, argue that Voronkov’s visit to the region helps legitimize the Chinese government’s narrative of counterterrorism, and worry that Bachelet’s visit, which she has repeatedly requested, would further ‘whitewash’ Beijing’s behavior in the region. Although Beijing argues that a visit will allow Bachelet to “see for herself,” critics argue that such visits, which are often heavily stage-managed by the government, risk legitimizing the system and enhancing the narrative that the Chinese government’s activities in the region are driven by security concerns, rather than being part of a concerted effort to suppress the culture of Uyghurs and other religious and ethnic minorities.

So what can we ‘see for ourselves’? Why is it necessary to act? And what are potential approaches to this crisis?

What we can see

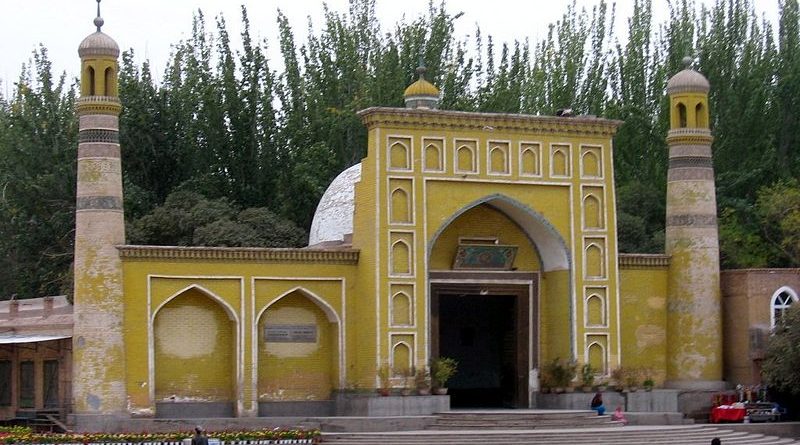

Two days before China’s representative to the UN in Geneva Chen Xu extended the invitation to Bachelet, satellite pictures revealed that the Chinese government destroyed the central Uyghur graveyard in Khotan, giving family members only six days to ID the graves of their relatives or risk them becoming “unclaimed corpses”. Investigations of satellite footage by Bellingcat and the Guardian found that at least 31 mosques and two major shrines “suffered significant structural damage between 2016 and 2018.

The destruction of cultural and religious sites provides context for the construction of ‘re-education centers’, which can also be tracked on satellite imagery. Speaking at a conference on the Uyghur crisis in DC last weekend, student researcher Shawn Zhang said he has identified 98 camps on satellite imagery. Adrian Zenz, a German-based researcher who has spoken widely about the situation in the Uyghur region, uses publicly available documents from the Chinese government to uncover information about the ‘re-education centers’ in the region. Although Chen claimed that “there are no so-called re-education camps” at a news conference hosted by the UN correspondents’ association, Zenz found that government documents from 2018 directly referred to the camps as re-education centers.

The combination of the destruction of cultural and religious sites, the satellite and financial evidence of heavily-secured internment camps, and government documentation regarding the purpose of those camps refute Beijing’s claims that combating terrorism is the sole purpose of its campaign of surveillance and detentions in the region. Annie Boyajian, director of advocacy at Freedom House, noted that a key advantage of advocacy in this area is that the situation in the region is generally not up for debate: “the question is not ‘tell me what’s happening’ but ‘what are some specific and creative ways we can use to address this.’”

So what are potential approaches to this crisis? And why is a change in approach necessary?

In light of the detention of one to two million people in Xinjiang, engagement with the Chinese government on counterterrorism and surveillance technology seems increasingly untenable. Voronkov’s visit to Xinjiang is just the most recent instance of how the Chinese government can use global action against terrorism to justify cultural and religious repression in the region. A more confrontational approach on the detention and surveillance of Muslim minorities is necessitated not only by human rights violations within the region, but because it has the potential to have global effects on the protection of human rights in counterterrorism and the use of technology to violate human rights. In order to do so effectively, countries must take a strong stance on human rights both in China and within their own borders while taking care to recognize the distinction between Chinese people and the Chinese government.

The US and others should examine supply chains that reach into Xinjiang and ensure that consumers are not making the repression of religious minorities profitable by purchasing goods created with forced labor. The Wall Street Journal discovered that several Fortune 500 companies, including Kraft Heinz and Gap, have supply chains that run through Xinjiang, where Muslim residents “are routinely forced into training programs that feed workers to area factories.” Several of these companies directly reference the International Labor Organization’s standards against the use of forced labor, meaning that a statement from the ILO on forced labor could engage action by these companies. Other potential avenues include action by the US unit on forced labor, or direct pressure on companies, which successfully convinced US clothing company, Badger Sportwear, to end its relationship with a supplier in the region.

US engagement with Chinese-based technology companies is a particular cause for concern, as AI and surveillance tools are used to restrict the freedoms of Muslim minorities in the region and of Chinese citizens more broadly. Buzzfeed revealed that US university endowments and retirement funds helped finance two Chinese facial recognition start-ups that developed the technology behind Beijing’s surveillance of Muslim minorities. US technology companies, including Microsoft, collaborate with Chinese companies and universities in the development of AI and facial recognition, which could be used in the region. While the system of surveillance in Xinjiang, which collects personal information on millions of ordinary citizens (as revealed by one unsecured database), is in itself a concerning violation of human rights, it is also part of a broader pattern of China’s use of technology to silence dissent both within its borders and beyond.

Freedom House’s most recent report on internet freedom finds that representatives from half of the countries included in their survey (36 out of 65) attended trainings and seminars on new media hosted by Chinese officials. In several cases, increased involvement with Chinese companies and participation in trainings hosted in China were followed by the passage of restrictive cybercrime laws. After representatives from Vietnam attended one such training, the country passed a cybercrime law that Freedom House says “closely mimics China’s own law” and that technology company officials and rights groups fear could be used to stifle dissent.

However, as US lawmakers urge companies and funds to consider divesting from companies involved in human rights abuses in Xinjiang and as the US government seeks to protect US research in science and technology, it is important to avoid engaging in similar racial discrimination by distinguishing between Chinese scientists and the Chinese government. Yangyang Cheng, a Chinese-born physicist writes compellingly on this subject, arguing that Chinese scientists’ “sense of patriotism and national belonging do not equate a blind acceptance of government policy” and that Chinese scientists should be involved in, and held accountable to, global norms on the ethical use of technology.

Failure to distinguish between the Chinese government and scientists of Chinese heritage will unnecessarily limit scientific collaboration and discovery, and may carry a heavy cost. Just last week, Bloomberg reported that the Trump administration’s push to counter the transfer of innovation to China from US research institutions has seen “FBI agents reading private emails, stopping Chinese scientists at airports, and visiting homes to ask about their loyalty.” The article tracks the case of one Chinese American scientist who was pushed out of her position at MD Anderson for connections with China, connections that the institution had previously encouraged her to develop. Chinese-named defendants are twice as likely to be wrongfully accused under the US Economic Espionage Act, according to Andrew Kim, a visiting scholar at South Texas College of Law. Visa restrictions on Chinese scientists may limit US access to top Chinese AI talent, which Macro Polo found is primarily trained and located in the US. Scrutiny of, and restrictions on, Chinese scientists based solely on their country of origin could result in the loss of this talent, and restrict collaboration on critical issues like public health and climate change.

Thus, as the US and others confront China on human rights violations in Xinjiang, it must remain engaged with individual Chinese people. Xiaorong, a Chinese scholar who spoke recently at the D.C. conference on the Uyghur crisis, stated that although there is widespread bias against Uyghur among the Han Chinese, it is important to remain engaged with the Han people: “there were voices of conscience. People have souls. So we have to put our faith, our belief in them.”

This requires the US and others not only to draw a clear distinction between the Chinese people and the Chinese government, but to ensure that their own actions do not blur the lines between religious identity and terrorism. As the US seeks to confront China on the internment of Muslim minorities, it must be aware of the role that the ‘War on Terror’ and Islamophobia in the West play in legitimizing this behavior. Sean Roberts, Associate Professor at George Washington University, noted that “in the general war on terror, [it] is not so unusual, that people look at an entire ethnic group or an entire religion, particularly as being a terrorist threat.” The US and others must consciously combat such conflation by avoiding policies like the ban on immigration from certain Muslim countries that equate Islam with threat and challenging associated rhetoric, limiting Beijing’s ability to justify the detention of Muslim minorities for the exercise of their belief and culture.

Multilateral action is also imperative to the clear communication of a human rights narrative on this issue. While US government officials, including Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi and Ambassador for International Religious Freedom Sam Brownback, have issued strong statements on the repression of Uyghur, unilateral US action risks being lost in the ongoing rhetoric of the US-China trade war, with US disengagement from technology companies involved in the surveillance of Uyghur minorities vulnerable to re-interpretation as an attempt to win the battle for standards in emerging technology. The global market also makes it difficult to effectively put pressure on supply chains reaching through Xinjiang without the involvement of multiple stakeholders.

As consensus emerges on the situation in Xinjiang, there is increasing awareness that human rights violations, including in the region fit the definition of a mass atrocity crime, activating new channels for multilateral action. One powerful venue for action is the International Criminal Court. Michael Polak, a barrister practicing in international law, notes that recent rulings regarding the Rohingya open the potential to prosecute China for forced deportation: a mass atrocity crime that includes the “forced displacement of the persons concerned

by expulsion or other coercive acts.” If Muslim minorities from Xinjiang seek refuge in a country that is an ICC member, the ICC would have jurisdiction to prosecute China, just as it was able to prosecute Myanmar (which is not a member of the ICC) for forcing the Rohingya to flee to Bangladesh (a member of the ICC). Another possible channel is the responsibility to protect (R2P), a duty of the country to protect the rights and security of its citizens, which is recognized globally, including by China. Unfortunately, the current administration’s attacks on several international forums make it more difficult for the US to engage some of these promising mechanisms for multilateral action, underscoring the need for cooperation with partner states.

The US Deputy Secretary of State John Sullivan voiced his deep concerns Friday that “the UN’s topmost counterterrorism official is putting at risk the UN’s reputation and credibility on counterterrorism and human rights by lending credence to these false claims,” a concern that was voiced by other Western governments as well. What should Bachelet do? Voronkov’s visit to the region was likely heavily managed, as was the government-sponsored April 2019 visit by foreign journalists, and it seems likely that Bachelet’s will be as well. Although NPR and others reported on their government-sponsored visit critically, it did raise concern that the images from the visit–increasingly important in social-media driven news–helped to advance Beijing’s narrative that the purpose of the centers was retraining, rather than suppression of cultural and religious identity. Would Bachelet’s visit do the same? While the images from her visit might be deceiving, the evidence of internment camps and destruction of cultural and religious sites makes it impossible to deny the aims of the Chinese government in Xinjiang, and her visit would provide an important counterbalance to that of the UN counterterrorism chief. However, it is even more critical that this visit occurs in the context of a multilateral commitment to confront China on issues of human rights in the region, even if it incurs political or economic costs. The risks to norms of human rights globally, and to the rights of millions of Muslim minorities specifically are too great. We must no longer do as Tiananmen student activist and member of the Uyghur community, Wu’er Kaixi, described, and ask the question about human rights without waiting for an answer. We must require an answer. And we must act.

Kendra Brock holds a Master of Arts from Seton Hall University’s School of Diplomacy and International Relations. Her specializations are International Economics & Development and Foreign Policy Analysis. Prior to beginning her graduate studies, she worked as an English teacher at a Chinese university for three years. She currently serves as the Deputy Editor-in-Chief of the Journal.