Are we a society obsessed with the absence of good, and the constant presence of bad?

You could argue that this obsession is not only real, but ingrained in society. It plagues the news, television programs, and movies. It’s on Netflix. It’s written in the fiber of our conversations and the subjects we choose to dwell on.

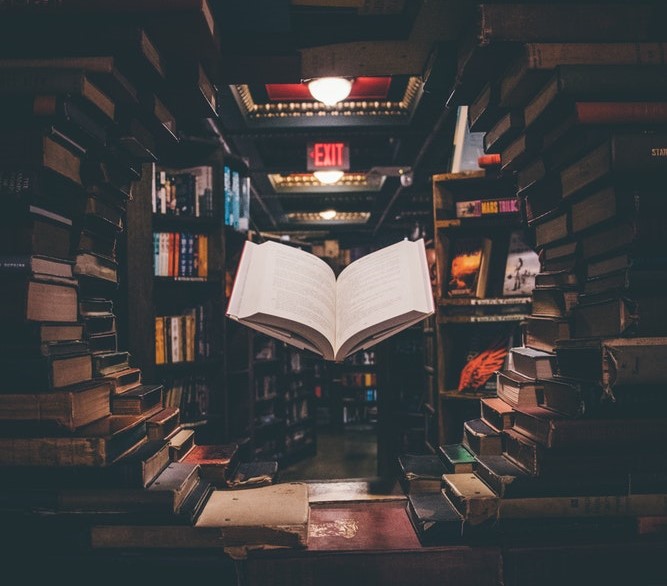

And it’s especially a part of literature, both in its theory and its contemporary craft. While everyone has their own taste in literature, it can be surprising to hear someone say they love well-known books like A Clockwork Orange, Lolita, or even a work as contemporary as The Kite Runner. It’s hard not to say, “Well, why?” What do you see in this literature that seems to spin deeper and deeper into darkness without much hope or relief by its conclusion?

It seems that literary studies—and literature in general— seems to have forgotten an element of grace. Not grace as in lightness or elegance—although that might be nice too— but the kind of grace, like God’s grace, that looks in the face of darkness and evil, and instead promises hope, change, and redemption.

Don’t misunderstand my words; this grace doesn’t need to be written into literature through the inclusion of God as a character or religious belief as the structure of a story’s climax. A perfect example of a novel that does approach literature in this way is Graham Greene’s The End of the Affair, a story that has been categorized as a Catholic novel and deals with the stuff that hurts—betrayal, jealousy, rejection—but ends in understanding and a turn toward hope, and an explicit turn toward faith. But as wonderful as Greene’s novel is, these themes can be even more powerful when they come solely through human means. Grace, forgiveness, and change can be most moving when they flow from an honest account of the feeling and subjectivity of the human experience and worldly means.

It’s true that novels that border on disturbing might be considered well-written. But even so, they push literature in the direction of complete despair. The rise in popularity of dystopian literature, like The Hunger Games or The Handmaid’s Tale, among many others, seems to show a constant focus and criticism on the dark matter of society, without much sign of change. Readers who made it to the end of The Hunger Games often note their disappointment in the lack of improvement or promise at its conclusion.

And in the discussions where theorizing about this literature happens, there can sometimes be a greater focus on the nothingness of literature than any kind of something-ness. Literature studies can feel like an archeological dig, but without any hope of finding an artifact or bone, and only focusing on the many holes instead. Those who hope to discover something in one of these holes or who sees the digging as meaningful can often be made to feel foolish. The conversation concludes that it’s the nothingness that somehow makes this worthwhile, and we come back next week ready to find nothingness, share nothingness, and go make our own holes, so that one day other people can find nothing too. And yes, not every conversation feels like this and many are rewarding and interesting, but when they turn to this discourse you might start to wonder “what’s the point of all this anyway?”

And there are many books that do this already, whether it’s symbolic and philosophical novels like Life of Pi and The Alchemist or more traditional novels like The Elegance of the Hedgehog. Even the young-adult book, The Fault in Our Stars, a novel about teenagers plagued with cancer, can make the reader cry like a baby and still contain much grace and fulfillment at its close.

These examples, among others, remind us that the characters we read and create should strive toward something greater than we could do or think ourselves, even if they fail in these endeavors. They should turn toward hope or change even if it’s only in the context of a tiny step. That tiny step can reverberate into grand effects that might not even be seen in the present.

However, even a tiny step in this direction can feel impossible or in vain, especially for a Christian. How can one with values and beliefs that seem so lost in culture these days begin to articulate his or her voice?

Literary theory might seem completely useless and irrelevant to someone set on intended purpose in all things as big as the world and as small as a chapter in a novel, but with some extra hard thought that the Church fathers and theologians would have wanted, these theories can be merged together. It sounds like strange concept, but for those whose faith is practically built on oxymoronic ideas and things that don’t seem to go together and somehow do, this kind of thought is normal, productive, and even expected.

A microscopic view of the world only sees destruction, greed, and egocentrism, which often gets reflected in art. But zooming out just a tiny bit to a wider view of time and the world might allow for hope and an understanding that even the worst of conditions can still accomplish good. This view might not have to zoom out so far that it encompasses the heavens and God, but if it just zoomed out a little, tiny bit, it might see that the universe is not such a void, and that there is still room for grace. It doesn’t assert that life is perfect, or that the world is perfect, or that these things should be perfect, but rather addresses the darkness and tries to bring light to it, like a sinner might address their burdens and turn toward redemption and grace for relief.

I think people are disappointed by literature that doesn’t lead them anywhere except themselves and the things they already know—namely that evil exists and that life can feel meaningless. People shouldn’t get to the end of a story or a literary theorist and think “well what’s the point?” and only receive an answer that the point is that there is no point. They shouldn’t feel like they are just looking in a mirror and seeing everything that’s already familiar about themselves, they should see what they could be and do, and what they can become. Most literature, and most elements of our culture, don’t live up to those stakes and goals.

I recently heard a deacon quote the phrase, “Live in such a way that those who know you, but don’t know God will come to know Him.” If you are wondering where to make a difference, you don’t have to spread the Gospel to a far-off country without Christianity. Those missions are all fine and well, but if you want to make an immediate difference now, all you have to do is look around you and the conversations that occur amongst your peers to see that the world of literature and the world of writing needs something new, something different, something uplifting and about redemption. Something that believes in grace.

If you’re a passionate Catholic or Christian who wants to see their voice in the material they read, you have to create that voice. It isn’t there for you to read and regurgitate as your own. It’s in-between the lines, usually in the context of opposition to your beliefs. There are models you can take after who have begun this task. Graham Greene, as mentioned earlier, is one. Another is Flannery O’ Connor, whose stories contain so much violence and vileness that we can recognize as a part of the “real world” but who nevertheless brings her characters and her readers to recognize their condition in a new way. These writers confront the bleak nature of reality and also use their language to recognize a beauty of the human condition, and the possibility for the human person to become a greater version of him or herself.

In a time where these meanings are too often lost, choose your entertainment wisely, and be a believer that you can become a better version of yourself. Have hope, believe in grace, and if you’ve been given the gift to write, write courageously.

Contact Kiersten at kiersten.lynch@student.shu.edu

Photo courtesy of Jaredd Craig on Unsplash