Guidebook: the United Nations Building

Located at 405 E 42nd Street right along the East River on Manhattan Island is a piece of international territory belonging to 193 nations which holds the United Nations Headquarters. In a city that is home to over 8 million people speaking perhaps 800 languages, it is not surprising that an international organization such as the United Nations would take New York City as its home. However, the location of the U.N. Headquarters in New York was not inevitable, rather it involved major international and national discussion on the part of the U.S. government and the newly-established United Nations. The complicated nature of the process is seen in the opposition from other American cities as well as in the doubts about the physical location ultimately offered up as the site of the United Nations. Since its completion in 1952, the building has served as a center for international conversation and negotiation within the realm of the highly globalized and diverse city of New York. It continues to exert influence over New York City today due to its function in the international community and its ability to attract people from all corners of the world. While the U.N. Headquarters and organization itself have changed over the years, the building has remained a landmark of the city and an international symbol of cooperation and progress.

The United States emerged from World War II on the side of the victorious allies, however, the world it entered was far different from the pre-war era. The two global wars of the first half of the twentieth century had revealed that the world needed a body to ensure peace on a global scale and to discuss and negotiate issues before they resulted in such devastation. Following WWI, the predecessor to the United Nations was established in the League of Nations in Geneva, Switzerland. The League of Nations was the first embodiment of many of the fundamental ideas that the United Nations would later embrace, however it proved to ineffective in guaranteeing international harmony given the acts of aggression that led to the outbreak of WWII. The United Nations was created at the end of the Second World War following the creation of the charter at the United Nations Conference on International Organization in San Francisco in June 1945, however the Headquarters were not a pressing topic of discussion until months after when various countries competed to be “center of international diplomacy,” as the U.N. became a reality.

The United Nations buildings in New York have served a far greater purpose than simply providing the office space for the bureaucratic system to function effectively and efficiently. Indeed, the pressure was on from the start for the headquarters to serve as more than a physical presence, with President Truman proclaiming: “These are the most important buildings in the world, for they are the center of man’s hope for peace and a better life. This is the place where the nations of the world will work together to make that hope a reality.”[1] The world had recognized the need for such an organization of world peace after the First World War with the League of Nations, however it did not truly embrace and support this vision until the creation of the United Nations.

Competition to be the world capital initially involved a debate over whether the U.S. or Europe offered a more suitable location for the new headquarters. Some believed that the “continent’s pressing needs,” required the U.N. headquarters to be housed within Europe. However, others argued that the “disarray,” of Europe did not allow for the “peaceful setting,” necessary for such an organization to be successful.[2] The memory of the “disillusions associated with the demise of the more European-oriented League of Nations,”[3] further pushed U.N. officials to advocate for America as the home of the future world capital. While the U.N. voted to locate its headquarters in the U.S. in 1945, the battle had already begun between various American cities for the prestige and economic benefit of hosting the headquarters. A subcommittee of the U.N. Preparatory Committee received bids from Boston, Massachusetts; Newport, Rhode Island; Atlantic City, New Jersey; the Black Hills of South Dakota; Chicago; Denver; Philadelphia; San Francisco; Miami, Florida; the state of Indiana; Hyde Park, New York; Navy Island near Niagara Falls; Cincinnati; New Orleans; and St. Louis among locales.[4] By December 1945, New England alone had offered up “at least twenty-three New England locales,” from Rhode Island, Massachusetts, Vermont, Maine, Connecticut, and New Hampshire.[5] The race to host the world capital was indeed an international affair despite the fact that the location was going to be American as many British leaders wanted to “secure the closest possible U.S. location,” and thus threw their support behind small New England and mid-Atlantic towns.[6] In January of 1946, the Stamford and Greenwich area of Connecticut was favored as a permanent site given that it was “so close to Manhattan, so attractive with its winding roads and wooded estates, and so apparently accommodating.”[7]

While Flushing Meadows, New York served as the “UN’s interim home,” the site-selection committee continued to search for a permanent site as the New England communities dropped out of the race and Philadelphia and San Francisco were locked in fierce competition in the fall of 1946. The committee had already changed its vision from a world capital, a city “much like the Vatican,” to “headquarters sites ranging from forty square miles to a miniscule two.”[8] Robert Moses and Neil Rockefeller pressed the influence of Flushing Meadows as the “temporary host to the United Nations,” in trying to sway the committee away from its desire to “establish an identity for the world body that would be distinct from that of any major American city.”[9] However, the committee seemed to be leaning in favor of Philadelphia in the early days of December in 1946. The delegates from Philadelphia and Pennsylvania lobbied for the City of Brotherly Love as it would “especially symbolize the underlying principles and ideals of the United Nations.”[10] Philadelphia was “ideologically and historically eminently suited to become the World capital of Peace, the permanent home of the United Nations and the nerve-center of the world machinery of peace;”[11] and it appeared that it would in fact become just that as many United Nations delegates expressed their support for Philadelphia over San Francisco, which was not located along “the eastern seaboard,” and New York, with its “skyscraper proposal.” [12] There will still those who had other visions in mind for the location of the headquarters, thus even if previous New York sites had been rejected there was still hope as long as there was money and influence.

The aspirations of Neil Rockefeller and architect Wallace Harrison to have the world capital in “Gotham,” rather than in the “Quaker City,”[13] proved to be substantial in this very intense competition. It was in true New York style that the property that would become the future home of the United Nations was acquired: business and commerce. John D. Rockefeller had to first acquire the land from Bill Zeckendorf, “New York’s most spectacular real-estate broker,” which required the exchange of millions of dollars in a dinner party conversation. The United Nations, which had been searching to become a world city of its own, now looked to “plans for an international office complex,”[14] and rapidly accepted John D. Rockefeller’s $8.5 million donation of an 18-acre property alongside the East River as the alternative to the Belmont-Roxborough sections of Philadelphia. The property was previously home to a row of slaughterhouses, giving it the nickname Blood Alley, and was also the site of the hanging of Nathan Hale by the British.[15] Rockefeller had first offered up this property on December 10th, 1946 and just four days later “the nations accepted the proposal by a large majority.” [16] This decision revealed the influence of money and power in the global world, especially when it came to the financial center of the world, New York City. Philadelphians resented this choice as they did not believe the “superficial, hard and cynical atmosphere of New York,”[17] was the proper environment for an organization of world peace and harmony. The race to become to home to the symbol of world peace had involved arguments of deeply-rooted traditions of liberty, tolerance, diversity, and democracy, yet ultimately the decision came down to “money, influence, and the UN’s desire to escape the perception that it had bungled one of its first important tasks.”[18] Ultimately, the Headquarters Agreement between the United Nations and the United States, signed at Lake Success on June 26, 1947, stated that “the premises bounded on the East by the westerly side of Franklin D. Roosevelt Drive, on the West by the easterly side of First Avenue, on the North by the southerly side of East Forty-Eighth Street, and on the South by the northerly side of East Forty-Second Street,”[19] were all the property of the United Nations and its member states, not of the borough of Manhattan. Thus, the center for international diplomacy and world peace would be housed at Turtle Bay overlooking the East River, however the ambitions for this project reached far beyond that 18-acre tract of territory.

Today the United Nations Headquarters serves as a “symbol of peace and a beacon of hope,” that attracts nearly one million visitors a year.[20] However, this status as a tourist attraction is not a new phenomenon for the U.N., but rather one that was established with the completion of construction in 1949. The Headquarters quickly began to attract massive crowds and by 1953, “five thousand visitors,” were touring the U.N. in a single day as it was quickly becoming “the country’s fastest-growing indoor tourist spot.”[21] Another part of the appeal of the United Nations Headquarters is its status as international soil, it is the “cheapest trip abroad,”[22] for many American citizens. The guided tours, which have been a feature of the U.N. since the completion of the building in 1952, are offered in up to 12 languages and serve as the connection between the public and the U.N. as they are integral in “shaping people’s perceptions of the work of the United Nations.”[23] While the title of Wharton’s article suggests that the U.N. buildings were creating chaos, the article itself only serves to show that the U.N. Headquarters were a source of immense attraction and interest. From the architecture to the artwork within the buildings to the bilingual signs to the salaries of the tour guides to the closed doors, everything about the U.N. buildings and the work that occurred within them engendered intrigue and fascination from the public. The United Nations Headquarters were indeed a “side show,” in that they transported people to a peculiar place that was unique for its time in both design and purpose.

The Headquarters consists of four buildings: the Secretariat building, the General Assembly building, the Conference building and the Dag Hammarskjöld Library. The Secretariat building was one of the first skyscrapers built in the international style, which attracted both awe and criticism in the early days of the United Nations. Designed by Le Corbusier, the Secretariat building’s international style was a reaction against the ornate Gilded Age and Art-Deco buildings of the early twentieth century. International style was a sleeker, simpler utilitarian style that was completely detached from the city grid and made use of late more glass, concrete, and steel. The Secretariat building received criticism for the international style of architecture as it did not exhibit the same aesthetic flourishing of earlier New York buildings. For some, the United Nations building was the “most beautiful building in New York,”[24] while others complained that the building did not “create fresh symbol,” due to this modern, international style of architecture. The Secretariat Building captures the eyes of all the visitors to the U.N. Headquarters, as it has since the day it was erected. The building, “a shimmering glass and marble slab,”[25] rises 39 stories high and has over 4,700 windows since “Everybody wanted an outside office.”[26] The Secretariat’s style was quite different from the surrounding architecture of the Tudor City apartments and thus it offered many different interpretations. From a “magnified radio console,”[27] to an “ice-cream sandwich,”[28] the Secretariat has received its fair share of metaphors due to the uniqueness of its design. Although the Secretariat building is just over 500 feet tall in a Manhattan skyline that soars to heights of nearly 1,800 feet, its green glass facade continues to catch the attention of those walking along 42nd Street.

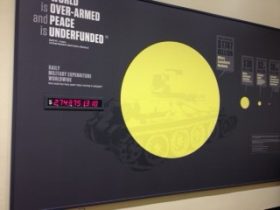

The international nature of the United Nations, beyond just hearing various languages, is revealed by just walking through the General Assembly building. There are murals painted on walls by artists from a multitude of countries; rooms filled with donations from countries that showcase their creativity and culture; exhibits that present the many issues that world leaders have dealt with continuously from the middle of the twentieth century and issues that have been given life by the advancements of the twenty-first century. The General Assembly conference room provides cultural intrigue in both language and art, with two iconic murals adorning its walls that have long been examined in awe and speculation. Fernand Leger’s two murals captivate visitors to the General Assembly auditorium and have sparked a lot of conversation in the past and present, having been dubbed “Scrambled Eggs,” and “Rabbit Chasing Himself.” The conference room is not only known for its massive space, which seats the 193 member states of the United Nations, but also its up-to-date technology. In the 1950s, this technology included systems offering multiple languages at the push of a button while today these projects include efforts at reducing energy consumption within the hall.[30] To step into the United Nations Headquarters is to step into another world, another time and place that is both our own and that of the many generations that preceded us. The simple experience of viewing the United Nations Headquarters is comparable to viewing the Statue of Liberty or the Freedom Tower, as it goes beyond just the architectural layout by offering a symbol of all the best efforts at world peace on a small strip of land in the city that never sleeps.

The vision had to be put into physical form in its new home in Manhattan, however this raised the standard complaints of any building project in a major city. New York City has long received criticism for being too crowded and for lacking space for growth, yet these issues did not prevent the U.N. Preparatory Committee from accepting John D. Rockefeller’s donation. Thus, the construction project itself, involving ten architects from different countries and materials from all over the world, spoke to the global nature of the home of the institution being built. The construction project also revealed, however, the many issues that come along with building in an urban space. New York City has always struggled with an ever-expanding population in an ever-limited space; however these issues were not enough to prevent the U.N. from being built there. The site alongside the East River offered “no possibility of expansion,” and it was “too small to give much opportunity for an architectural setting.”[31] Thus, as is often the case in New York, the architects looked to build upwards rather than outwards. The space certainly would not accommodate the “housing needs,” of over 50,000 people that came along with U.N. community.[32] New York was the home of an “oversupply of people and traffic,” and an “undersupply of space and air-and a water shortage,”[33] however what it stood for as a symbol was far more appealing than what it lacked as a physical space.

The original hopes had been for a world capital city of its own merit, yet the United Nations instead opted for a city within a city, a concept which is not foreign to New York. The United Nations Headquarters are a “little city of all nations,” much in the same way that New York City itself is a city compromised of an extremely diverse population. While the United Nations was offered Philadelphia, “an area steeped in the history of the American quest for political freedom and democracy,” it instead chose the “more cosmopolitan, more communication and trade-centered, more culturally diverse, and perhaps the more socially appealing atmosphere of mid-Manhattan.”[34] The buildings stood as symbol for the future progress of the world, “a workshop for peace,” [35] as chief architect Wallace Harrison dubbed the headquarters. Harrison proclaimed that the project was “a work of genuine collaboration-what the UN ought to be. No one man or nation could call it his own.”[36] A global city on the scale of New York, a center for finance, commerce, and culture, came to take on yet another title: center for world peace. Just as New York City is always changing its physical appearance, building and rebuilding, so too is the United Nations as the organization continues to grow to meet the needs of the twenty-first century world. However, through all the change both New York and the United Nations Headquarters serve as symbols of potential, both in its greatest and most terrible forms. Just as New York City has the ability to represent both the best and worst aspects of urbanization, industrialization, and growth, so too does the United Nations offer the possibility of all the best that mankind can do together, but also all the tragedy and devastation that mankind is capable of inflicting upon itself.

[1] Truman, Harry S. “Address in New York City at the Cornerstone Laying of the United Nations Building,” (October 24, 1949), Public Papers of Harry S. Truman, 1945-1953, http://trumanlibrary.org/publicpapers/index.php?pid=1063 (accessed October 4, 2016).

[2] Mires, Charlene. “The Lure of New England and the Search for the Capital of the World.” The New England Quarterly 79, no. 1 (2006): 37-64. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20474411, 40.

[3] Atwater, Elton. “Philadelphia’s Quest to Become the Permanent Headquarters of the United Nations.” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 100, no. 2 (1976): 243-57. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20091055, 246.

[4] Mires, Charlene. “The Lure of New England and the Search for the Capital of the World,” 41-42.

[5] Ibid., 43.

[6] Ibid., 42.

[7] Ibid., 59.

[8] Ibid., 40, 61.

[9] Mires, Charlene. “The Lure of New England and the Search for the Capital of the World,” 62.

[10] Atwater, Elton. “Philadelphia’s Quest to Become the Permanent Headquarters of the United Nations,” 243.

[11] Quoted in Ibid., 244.

[12] Ibid., 251, 253.

[13] Snow, Edgar. 1950. “WORLD CAPITAL ON TURTLE BAY.” Saturday Evening Post 222, no. 51: 28-114. Academic Search Complete, EBSCOhost (accessed October 4, 2016), 106.

[14] Mires, Charlene. “The Lure of New England and the Search for the Capital of the World,” 63.

[15] Snow, Edgar. 1950. “WORLD CAPITAL ON TURTLE BAY,” 107.

[16] Ibid., 108.

[17] Atwater, Elton. “Philadelphia’s Quest to Become the Permanent Headquarters of the United Nations,” 256.

[18] Mires, Charlene. “The Lure of New England and the Search for the Capital of the World,” 62.

[19] “Headquarters Agreement between the United Nations and the United States of America, Signed at Lake Success, June 26, 1947.” International Organization 2, no. 1 (1948): 164-72. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2704224.

[20] “More About the UN,” http://visit.un.org/content/more-about-un (accessed November 12, 2016).

[21] Wharton, Don. 1953. “Manhattan’s Biggest Side Show.” Saturday Evening Post 225, no. 45: 40-129. Academic Search Complete, EBSCOhost (accessed October 2, 2016), 40.

[22] Wharton, Don. 1953. “Manhattan’s Biggest Side Show,” 40.

[23] “Tour Guides,” http://visit.un.org/content/tour-guides (Accessed November 10, 2016).

[24] Tucker, T. (1953, Mar 07). Trip to UN buildings enjoyed by cooperites. New York Amsterdam News (1943-1961) Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/225755684?accountid=13793

[25] “Art: Cheops’ Architect.” September 22, 1952. Accessed November 10, 2016. http://content.time.com/time/subscriber/article/0,33009,822508-1,00.html.

[26] Snow, Edgar. 1950. “WORLD CAPITAL ON TURTLE BAY,” 113.

[27] “Art: Cheops’ Architect.” September 22, 1952. Accessed November 10, 2016. http://content.time.com/time/subscriber/article/0,33009,822508-1,00.html.

[28] Snow, Edgar. 1950. “WORLD CAPITAL ON TURTLE BAY,” 113.

[29] Wharton, Don. 1953. “Manhattan’s Biggest Side Show,” 124.

[30] Ibid., 124.

[31] Gutheim, Frederick. “The Last Skyscraper.” Nation 163, no. 26 (December 28, 1946): 755. Points of View Reference Center, EBSCOhost (accessed November 14, 2016), 755.

[32] Gutheim, Frederick. “The Last Skyscraper.” Nation 163, no. 26 (December 28, 1946): 755. Points of View Reference Center, EBSCOhost (accessed November 14, 2016), 756.

[33] Snow, Edgar. 1950. “WORLD CAPITAL ON TURTLE BAY,” 113.

[34] Atwater, Elton. “Philadelphia’s Quest to Become the Permanent Headquarters of the United Nations,” 257.

[35] “Oscar Niemeyer and the United Nations Headquarters (1947-1949),” https://archives.un.org/content/oscar-niemeyer-and-united-nations-headquarters-1947-1949-0 (accessed November,

[36] Snow, Edgar. 1950. “WORLD CAPITAL ON TURTLE BAY,” 106.

Annotated Bibliography

“Headquarters Agreement between the United Nations and the United States of America, Signed at Lake Success, June 26, 1947.” International Organization 2, no. 1 (1948): 164-72. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2704224. Accessed September 22, 2016.

This source provides useful insight into the democratic process by which the U.N. headquarters came to be placed in the United States. It represents an agreement between the international organization and the American government which details the status of the headquarters on American soil.

Snow, Edgar. “WORLD CAPITAL ON TURTLE BAY.” Saturday Evening Post 222, no. 51 (June 17, 1950): 28-114.Academic Search Complete, EBSCOhost. http://eds.b.ebscohost.com/eds/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?sid=19fec28a-1153-4908-9f75-c4e7593ece61%40sessionmgr105&vid=1&hid=114. Accessed October 4, 2016.

This source discusses the maneuvers taken by private individuals to build the U.N. Headquarters in New York as it faced competition from other major U.S. cities. Every aspect of the construction project exemplified the international nature of the organization and thus reinforced its symbolic nature on world scale as a source of collaboration. However, this article also reveals that the decision to place such a large and monumental building in such a city was not without the usual urban problems of overcrowding, lack of space, increased traffic.

Wharton, Don. “Manhattan’s Biggest Side Show.” Saturday Evening Post 225, no. 45 (May 9, 1953): 40-129.Academic Search Complete, EBSCOhost. Accessed October 2, 2016.

This source speaks to the ability of the United Nations building to appeal to diverse people from many different backgrounds. It shows how the U.N. headquarters in New York reinforces the overall diversity that characterizes the city itself, demonstrates its function as a tourist attraction, and reveals its status as “international soil.”

Gutheim, Frederick. “The Last Skyscraper.” Nation 163, no. 26 (December 28, 1946): 755. Points of View Reference Center, EBSCOhost. Accessed October 4, 2016.

This source offers insight into the problems, both practical and theoretical, of the location of the U.N. Headquarters building on the East River site. These problems include those typical of an urban setting: the subsequent increase in population, the lack of space for growth, and the need to build vertically and accommodate all the demands of such an international community.

Tucker, Travis. “Trip to UN Buildings Enjoyed by Cooperites.” New York Amsterdam News (1943-1961), Mar 07, 1953, City edition. http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.shu.edu/docview/225755684?accountid=13793. Accessed September 22, 2016.

This source is useful in its examination of the allure and prestige to the general public of the new U.N. building. It can be used in collaboration with Wharton’s article to show that the building offered an exciting experience for ordinary citizens given its efforts at world peace and various architectural features.

“FACT SHEET: HISTORY of UNITED NATIONS HEADQUARTERS.” Public Inquiries, UN Visitors Centre. Accessed September 22, 2016. http://www.un.org/wcm/webdav/site/visitors/shared/documents/pdfs/FS_UN%20Headquarters_History_English_Feb%202013.pdf

This source provided by the U.N. Visitors Center offers information about the process by which New York became the home of the U.N. Headquarters. It also speaks to the extent to which the design and construction of the buildings represent the international character of the organization.

Mires, Charlene. “The Lure of New England and the Search for the Capital of the World.” The New England Quarterly 79, no. 1 (2006): 37-64. http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.shu.edu/stable/20474411.

This source offers insight into the beginning vision of the United Nations Headquarters as a symbol of world unity and international peace that needed a home that would suit its needs of international diplomacy. Rather than focusing on New York, this source draws attention to the appeals of New England cities and thus demonstrates that the road to housing the United Nations in New York was one filled with many bumps, from both within the U.S. and abroad.

Atwater, Elton. “Philadelphia’s Quest to Become the Permanent Headquarters of the United Nations.” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 100, no. 2 (1976): 243-57. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20091055.

This source shows the degree of competition offered by Philadelphia in the race to become the location of the headquarters of the United Nations. Philadelphia offered a tradition of liberty, democracy, and modern government that rivaled the campaigns of New England towns, San Francisco, and New York. This source also provides insight into arguments against New York City as the ultimate location by asserting that the environment of New York City was not as welcoming or conducive to world peace as that of Philadelphia.

Truman, Harry S. “Address in New York City at the Cornerstone Laying of the United Nations Building,” (October 24, 1949), Public Papers of Harry S. Truman, 1945-1953, http://trumanlibrary.org/publicpapers/index.php?pid=1063 (accessed October 4, 2016).

The words of President Truman reflect the optimism and eagerness with which many embraced the world organization. This source offers extremely powerful insight into the symbolism of the U.N., and thus the symbolism that the headquarters itself would take on. Truman addresses the global nature of the U.N. and its aspirations for world peace and international cooperation, concepts that would be echoed by architects and visitors to the headquarters alike.

“More About the UN,” http://visit.un.org/content/more-about-un (accessed November 12, 2016).

This source provides basic information about the U.N. headquarters as a tourist attraction, including statistics about the number of visitors per year. It will be used to demonstrate the appeal of the U.N. and to speak to its symbolism in the international community.

“Art: Cheops’ Architect.” September 22, 1952. Accessed November 10, 2016. http://content.time.com/time/subscriber/article/0,33009,822508-1,00.html.

This source discusses the architectural aspect of the construction project of the headquarters, from the issue of style to the problems of space and money. It provides a perspective from a popular culture magazine and thus speaks to some of the conversation surrounding the headquarters’ location in New York City.