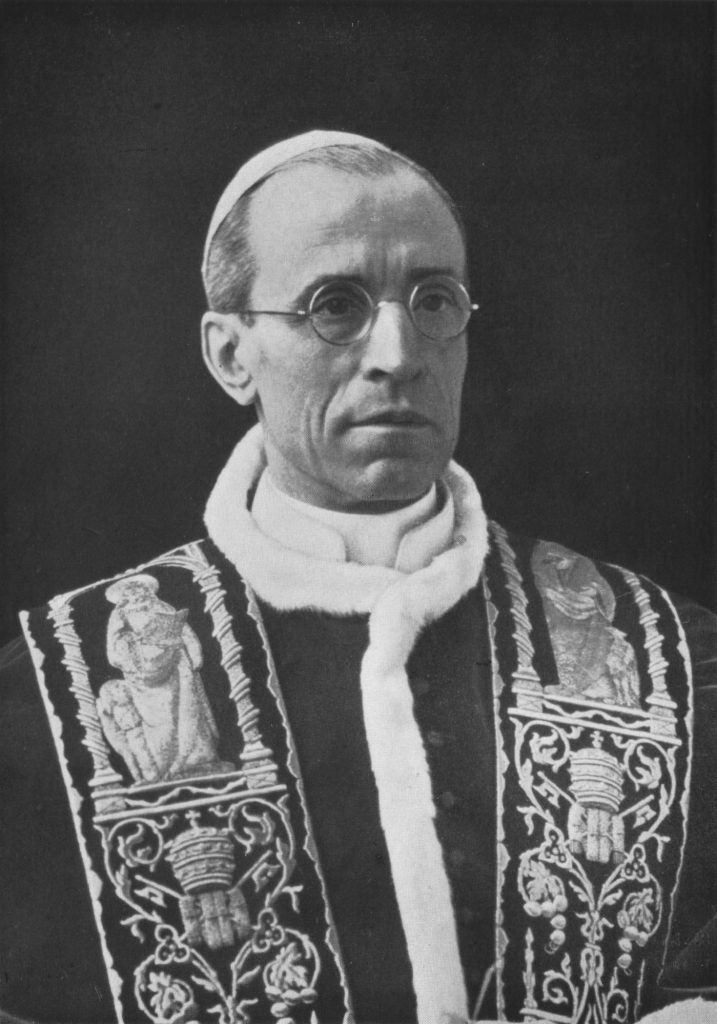

On March 2, 2020 the Vatican Archives for the reign of Pope Pius XII (1939-1958) were opened for access by qualified researchers. The usual period of time before the documents relating to a papal reign are accessible has been 75 years. Pope Francis has hastened the opening in this case in response to the keen interest shown in several quarters. It might be noted that scholars, Fathers Robert Graham and Pierre Blet and others, had made twelve volumes of materials from the World War II era available, except for documents referring to persons who were still alive in 1965 (Actes et documents du Saint Siège relatifs à la Seconde Guerre Mondiale). Now that 62 years have passed since the death of Pope Pius, it is unlikely that anyone mentioned in the archival holdings is still alive. Scholars can scrutinize these documents in order to develop a clearer insight into the issues that interest them.

Among the reports relating to this occasion, that of Ms. Lisa Palmieri Billig of the American Jewish Committee offers a detailed review: “Opening of Pius XII Archives: To speak or not to speak: that was the Question.” Steve Lipman’s report in the Jewish Week of March 3, 2020 quotes Jewish leaders in interfaith dialogue.

As we examine our conscience in preparing to worship, we acknowledge failure in thoughts, words, deeds and omissions. To what extent will Pope Pius XII’s reasons for failing to speak bluntly be evident from the archives? A serious reason for Pope Pius XII’s circumspection during the War years has been presented by Mark Riebling in Church of Spies: The Pope’s Secret War against Hitler (New York: Basic Books, 2015). In his review for Holocaust and Genocide Studies (2016) p. 558-60, Father Kevin Spicer of Stonehill College, who has worked extensively on the German Church and clergy during the Nazi period, comments: “[Mr. Riebling] does offer evidence of contact between the Holy See and German resistance, but fails to substantiate any direct linkages… Only the opening of the papers of Pius XII’s pontificate, together perhaps with research in other repositories, will enable us to evaluate fairly the Pope’s legacy in the face of the Holocaust.” This investigation is now possible, so we wish researchers well in their work!

The death of Mr. Rolf Hochhuth in Berlin on May 13, 2020, was the occasion for a lengthy obituary in The New York Times. As older readers may recall, the play Der Stellvertreter (The Deputy) dramatized the accusation that Pope Pius XII was silent regarding the persecution and genocide perpetuated against European Jewry. As a young German who struggled with the question of responsibility for such a horrendous destruction of life, Hochhuth strove to make the Pope responsible. He is quoted as writing: “Perhaps never before in history have so many people paid with their lives for the passivity of one single politician.” Thus, questions about the ascent of Adolf Hitler to the highest office in German political life and German acquiescence to the atrocities of his dictatorship were avoided. “For the Germans (the performance) was catharsis,” according to Louise Kerz Hirschfeld, quoted in the obituary. For some people, theatre and film productions have become an ersatz religion, seeming to provide a way to deal with issues of conscience. Did a question enter the minds of those “purified” by seeing The Deputy: “Would people like me listen to the Pope if he had spoken in crystal clear terms? Would we be moved into defiance of Nazi power? How would we have dealt with the inevitable reprisal?”

Among the statements by the national Catholic hierarchies of Hungary, Germany, Poland, Holland, France, Switzerland, Italy and the United States, published in the booklet Catholics Remember the Holocaust (Washington: U.S. Catholic Conference, 1998), I draw attention to that of the German bishops. They acknowledge: “We looked too fixedly at the threat to our own institutions and remained silent about the crimes committed against the Jews and Judaism” (p. 11). Recently, on the 75th anniversary of the end of World War II in Europe, the German bishops have examined the record of their predecessors during the Nazi era: see The Tablet of May 11, 2020. The German Bishops’ 25 page document, which you may access here, will be examined carefully by people of many backgrounds. Relations between religious leaders and the political forces of many nations in our time should be scrutinized for lessons that spring from this analysis of the Churches in the Nazi era.

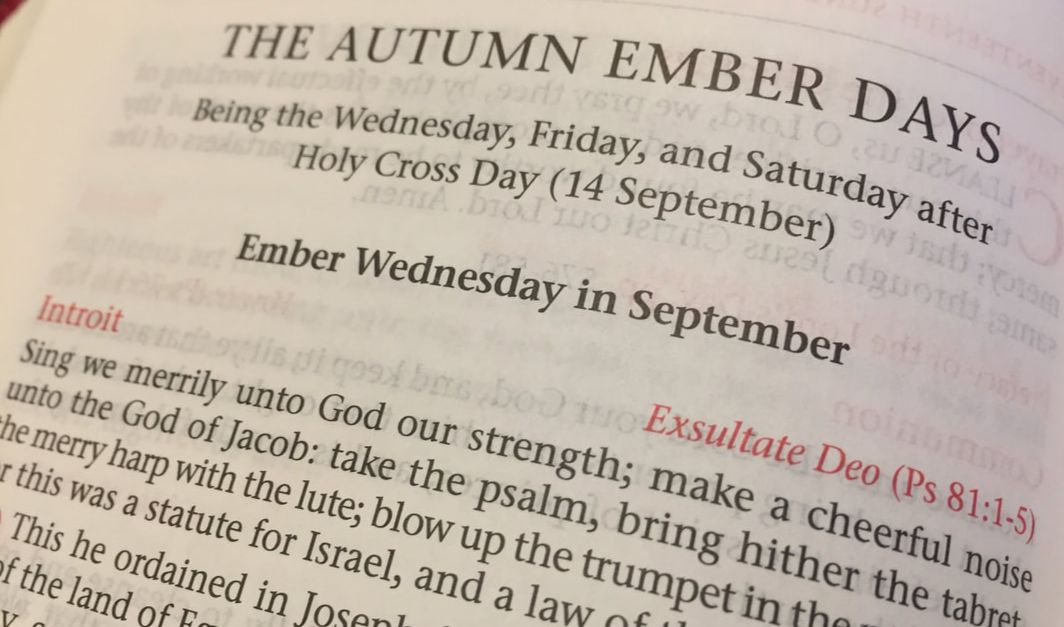

During a discussion among medievalists on prayer, I mentioned the ember days in the Church’s liturgy. Middle-aged participants asked: “What are ember days?”

During a discussion among medievalists on prayer, I mentioned the ember days in the Church’s liturgy. Middle-aged participants asked: “What are ember days?”