Public Investors Will Never Win – Thank the Private Markets

Mark Walier

Tech Editor

Despite the narrative of democratized investing being pushed by mobile trading apps, the “Gamestop Frenzy”, and the market share of retail investors growing from 10% in 2011 to 22+% 2022… the financial whales still gatekeep the best features of Wall Street for themselves. Private markets have locked up the best opportunities and thrown away the key. Inequity among investors has become increasingly apparent when evaluating the decrease in the value creation offered by U.S. IPO markets.

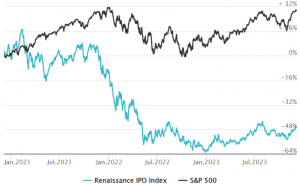

In 2021, the IPO market boomed, introducing 397 new companies and generating over $142 billion in proceeds. However, most investors involved in the excitement have seen negative returns far below those of the S&P 500 (see chart). In 2022, higher rates and recession fears kept investor funds on the sideline. By 2023, the IPO market rebounded as 100+ new offerings have hit the public markets to date. Despite the optimism, new IPOs have continued to deliver lackluster returns. The most recent IPOs to dominate market headlines, such as Instacart, Cava, Better.com, and chip-maker Arm, have generated double-digit negative returns since their offering date. What’s causing the IPO’s fall from grace?

Although it may feel that the issue lies in the structure of IPOs and their growing resemblance to pump-and-dump schemes, the real concern is their diminishing significance. The focal point of financial capital has transitioned from public to private, a shift occurring gradually but quietly. Venture capital firms, who have performed tremendously well over the past 20 years, have been injected with tens of billions of dollars to invest in pre-IPO firms. Now, private investors have taken advantage of the opportunity to capture the entirety of a business’s value creation before letting the public markets have a sniff.

As private markets continue to safeguard their most promising investment opportunities from public access, the quality of IPOs are declining. In 1980, roughly 90% of tech IPOs were profitable before being offered to the public markets. By 2021, that number shrank to just over 20%. One may think that tech companies are merely opting for earlier-stage IPOs. However, this is not the case. Instead, private companies have grown to their largest valuations ever (see WeWork: $47 billion) before ever considering a pubic market interaction. In fact, the last decade contained such an injection of private capital that private companies with a $1+ billion valuation were dubbed the nickname, “unicorn”. When this category of phenomenons was defined in 2013, 39 unicorns existed. Now, there are 1,220. Companies are not going public earlier in their growth stage, but instead are growing to epic proportions before offering a sliver of value to the retail investor.

Without the necessity for financing from public markets due to the endless flow of dry power into private markets, private equity firms will persist in funding a company until it reaches one of two stages. Either the company becomes strong but mature and investors believe that the growth stage returns have already been realized. Or, until its business model becomes questionable, prompting existing shareholders to employ a series of deceptive signals to attract less-informed investors. Only then does the public investor get their first chance to join in.

Ironically, we’ve also seen initial public offerings become less public. Historically, bankers sell the first shares to their favorite institutional customers. However, the proportion of private investors who hold onto the initial float (percentage of the company available to the public) has increased. To successfully sell shares to institutions, banks have effectively marketed their ability to create an initial trading “pop” in price. Despite potentially leaving money on the table, companies have been willing to sacrifice some proceeds in order to inspire a positive trading buzz around their stock. To artificially achieve this, IPO structures have decreased their float size. In 1980 the median IPO float was 29% of the total shares. In 2022 that number was 15%, the lowest in 42 years. Additionally, a lower float size allows private investors to retain greater control of the company. As basic economics suggests, artificially lowering supply (coupled with creating sufficient excitement) will cause demand for shares to increase, leaving retail investors with a late invitation to the party, a higher price of entry, and a lack of sufficient control. There appears to be a trend here.

But wait, aren’t institutional investors subject to a 180-day lockup period before they can sell their first IPO share? Well, those are going away. In 2021, the percentage of IPOs featured shorter lockup agreements, allowing insiders to sell before 180 days, reached an all-time high of 25%. Thankfully, the market has recently begun popularizing direct listings as an alternative to the traditional IPO format, promising to skip the road shows and offer a more democratic system. Wait, not so fast… direct listings contain no lockup periods, allowing institutions to dump shares before the retail investor can open their Robinhood app. Go figure.

Despite my obvious envy, there are reasons to consider why the financial world is rewarding private markets. After all – it’s rare to find any company executive who enjoys being under the watchful eye of the public markets, where investors ruthlessly demand quarterly performance. In the private markets, billion-dollar unicorns can frolic in a sea of capital for years before it’s time to turn in meaningful results. This often allows long-term growth strategies to play out, which is rarely possible when relying on the support of the short-sighted public markets. And, when times get hard, there’s almost always a deep pocket willing to keep the fun going. However, when private companies turn to the public markets and openly share their goal of “enhancing the world’s consciousness” (sorry, WeWork), they receive a cold reception.

While private equity soars and accredited investors enjoy rich profits, public investors—representing the broader population—have limited access to the markets where wealth is generated. As capital consolidates, so does influence. The “shareholder class” has historically been an exclusive group. Yet, at one point, it extended to the moderately affluent and subsequently, through pension and retirement funds, to the masses. As a result, wealth spread, influence was dispersed, and capitalism became more democratic. The transparency requirements of public ownership safeguard against collusion, corruption, and the progression toward a society dominated by monopolistic influences. The IPO markets are increasingly becoming another mechanism for transferring wealth from the have-nots to the haves, the poor to the rich, and the public to the private.

Contact Mark at mark.walier@student.shu.edu