Minsky Business: The Minsky Brothers and Burlesque in New York

The twentieth century is widely viewed by historians as the beginning of mass, commercialized leisure activities in America. As was the case with most major changes that took place in America during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, New York was at the heart of America’s new leisure culture. For many New Yorkers during this time, this new mass leisure took the form of wholesome, family-oriented activities such as vaudeville shows, movies, and trips to Coney Island. However, for those of a somewhat less respectable bent, there was another option available: burlesque.

“Burlesque” was and is a difficult thing to define, and often meant different things in different places and times. However, the type of burlesque that dominated New York from roughly 1910 until 1940 was a fairly uniform concept. At its most basic, this type of burlesque, referred to by historian Burton W. Peretti as “stock burlesque,” consisted of shows featuring sexually suggestive humor and songs, as well as striptease dancers.[1] Though there were many burlesque producers and many burlesque theaters during this time, no name loomed larger in the world of burlesque than that of “Minsky.” The four brothers Minsky, Abraham Bennett “Abe” Minsky, Michael William “Billy” Minsky, Herbert Kay “H.K.” Minsky, and Morton Minsky, would both build a burlesque empire spanning several states, and become some of the most famous New York show business personalities of their time, even if they are largely forgotten today. Yet the Minskys were not the crude flesh-peddlers that the moral reformers and politicians of the time attempted to paint them as being. Rather, they were intelligent men with good heads for both business and spectacle, men who would, almost by accident, play a major role in defining both New York and American popular culture for decades.

The Minskys’ journey into the world of burlesque began, according to Morton Minsky, in 1912, when their father, Louis Minsky, helped to construct the National Theater (later the National Winter Garden) at 111 East Houston Street[2]. The Minsky brothers became directly involved with the National soon after when Billy Minsky, then a newspaper reporter, decided to change professions after he was nearly murdered by a criminal whose activities he had helped to expose[3]. Although the National initially showed a combination of films and vaudeville acts (then referred to as “pick-vaud”), declining attendance due to competition from other theaters of the same type forced a transition to burlesque shows by the end of the 1910s[4].

Initially, the Minskys’ performance in show business continued to be middling at best, despite the transition to burlesque. Business rose dramatically, however, when the Minskys began to emphasize the sexual, as opposed to the comedic, aspects of burlesque, gradually placing a heavier and heavier emphasis on striptease dancers rather than comedians.[5] Perhaps the single greatest facilitator of this new form of burlesque was the idea of the runway, allegedly borrowed from the Follies Bergere in Paris, which allowed performers to interact more directly with the audience[6]. In addition to showing considerably more skin than most of their competitors, the success of the National Winter Garden was further enhanced by Prohibition, which enticed wealthy New Yorkers to “slum it” in the Lower East Side in search of entertainment and liquor[7]. All of these factors combined led to a boom time for the Minskys, who soon began eying venues far beyond the immigrant ghetto where they had grown up.

The Minskys’ first push out of the Lower East Side came in 1922, when Billy Minsky acquired the Park Theater at 5 Columbus Circle[8]. Though early performances reviewed well, ticket sales remained low, and the Minskys were forced to leave the Park only a year later[9]. The Minskys did not give up, however, soon acquiring the Little Apollo Theater on 125th Street, which, according to Morton Minsky, was soon taking in net profits of around $20,000 a week[10]. This success allowed the Minskys to expand further, buying out competing theaters and consolidating their hold on burlesque in New York City[11].

In addition to increased financial success, the demographics of the Minskys’ audience began to change as well during this time, as their shows attracted more and more “highbrow” clients such as doctors and authors, adding to their traditional base of working-class immigrants[12]. However, this new visibility also brought problems, namely the beginning of periodic raids by police and moral reformers who sought to combat the sexually charged dancing and suggestive comedy material that formed the basis of Minsky shows[13]. While certainly annoying, these raids were not yet a serious threat to the Minskys; as Morton Minsky later remarked, “But we [the people of New York] were still in the Jimmy Walker era, and official censorship was rare.”[14] These early attempts at censorship certainly did nothing to impede the Minskys’ meteoric rise, as they began to be involved with theaters outside of New York as well, hearkening back to the traveling “wheels” that had given rise to burlesque in the first place[15].

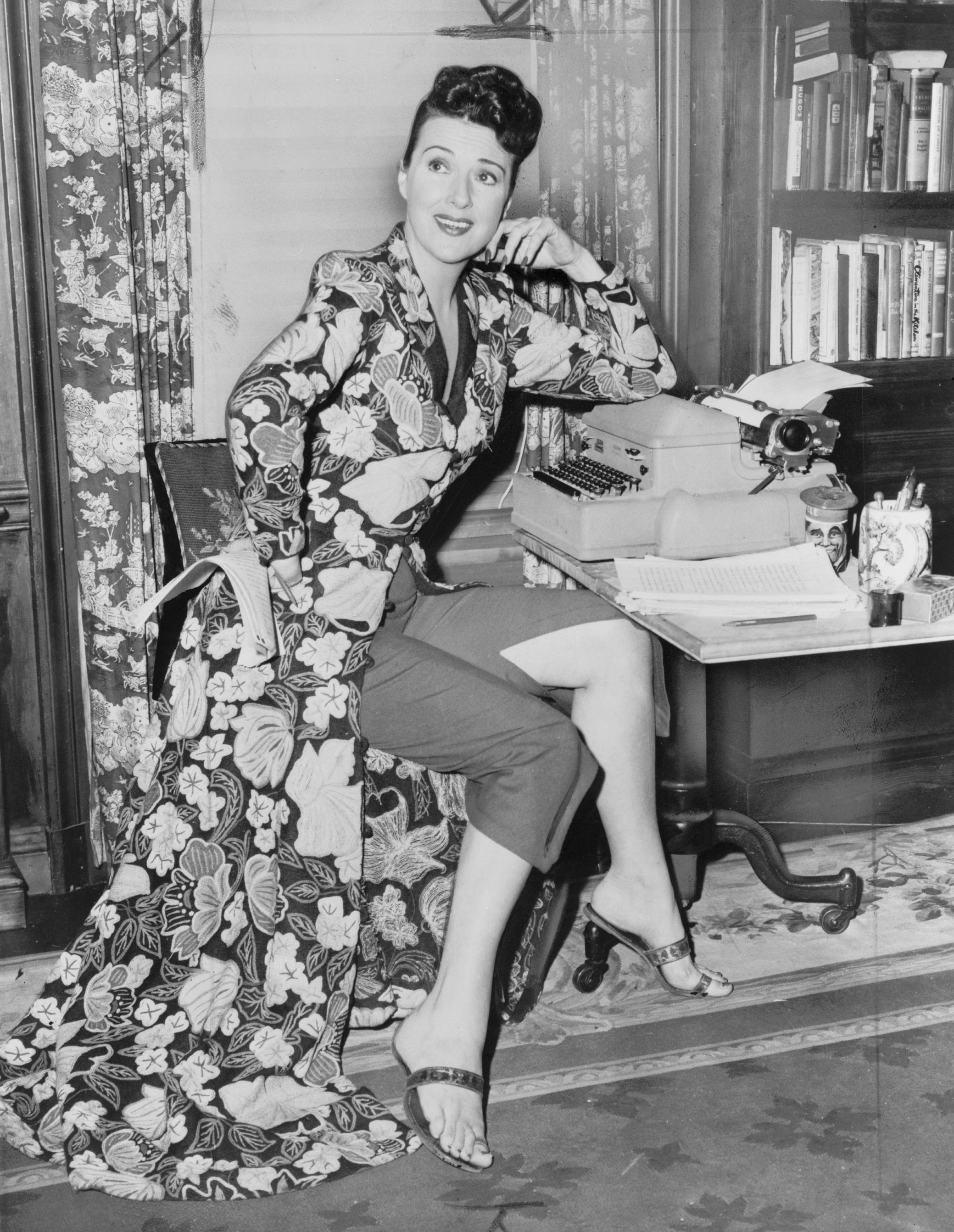

Though many businesses in New York suffered during the Great Depression, the Minskys actually experienced a business boom as the newly unemployed flocked to low-cost entertainments such as burlesque shows[16]. The Minskys enjoyed many great successes during this time: to begin with, they acquired the Republic Theater on 209 West 42nd Street, allowing them to break into Broadway for the first time, a longtime dream of Billy Minsky.[17] In addition, the Minskys were able to recruit a stable of ace strippers, including Ann Corio, Georgia Southern, Margie Hart, and the legendary Gypsy Rose Lee, whose act was once described by Billy Minsky as, “’Seven minutes of sheer art.’” [18] Furthermore, the Minskys were able to recruit a crop of skilled comedians, such as Phil Silvers, who had been forced to leave the “Borscht Belt” resorts of the Catskill Mountains due to the poor economy[19]. With around eleven thousand people attending shows at the Republic each week, the Minskys were well on their way to achieving parity with the biggest Broadway producers[20].

However, the early 1930s were not all positive for the Minskys. For one thing, the National, the Minskys’ first theater, was force to close in 1931 due to declining attendance caused by the gradual emptying of the immigrant neighborhoods that had sustained it in its heyday[21]. Trouble also hit the Minskys on a personal level; in June of 1932 Billy Minsky died at the age of 41 of Paget’s Disease, a degenerative bone disorder, depriving the Minskys of their creative head[22]. Soon after that, Abe Minsky, who had been gradually drifting away from his brothers for years, broke with them entirely and struck out on his own, taking control of both the Gaiety Theater at 1547 Broadway, as well as the New Gotham[23]. Though later newspaper reports would accuse Abe of attempting to go “highbrow,” the reality of the situation was more complicated than this[24]. According to Morton Minsky, while the shows at the Gaiety did aspire to be more artistic than the usual Minsky fare, those staged at the New Gotham were actually cruder and more overtly sexual than was common at the time[25].

However, the fracturing of the family would not be what eventually brought down the Minsky empire. The trouble began in 1934, when reformist politician Fiorello La Guardia succeeded John O’Brien as Mayor of New York, and appointed Paul Moss, himself a veteran member of the city’s theater community, as City License Commissioner[26]. La Guardia and Moss began a crackdown on burlesque shows in the city, supported by a broad coalition that included Broadway showmen, who feared competition from cheaper burlesque shows, small business owners, who thought burlesque houses attracted criminals, and moral reformers, who claimed burlesque encouraged prostitution and sex crimes[27]. Despite the crackdown, the Minskys and most of their fellow burlesquers were able to continue operating, albeit under somewhat greater restrictions, with Herbert and Morton Minsky moving from the Republic Theater to the Oriental Theater, near the intersection of Broadway and 51st Street, in 1936[28]. There, the two brothers evidently planned to make a permanent home, staging grand burlesque shows that would have made their late brother Billy proud[29].

This grand vision, however, was not to be. Soon after the move to the Oriental, La Guardia and Moss began their final assault on burlesque. Beginning with the conviction of the stage manager of Abe Minsky’s New Gotham for a minor violation in 1937, Moss imposed increasingly restrictive rules in burlesque shows, eventually pulling the licenses of almost all burlesque theaters that same year[30]. The Minskys were singled out with special invective, with Commissioner Moss stating that the Minskys were “defiant” and that they could not be trusted to operate a theater[31]. Though the Minskys soon received a new license via legal action, they could no longer turn a profit under the new rules, and, after a final failed attempt to produce an all-black vaudeville show, the last Minsky theater closed in 1937[32]. In a final insult, the Minskys were legally barred from associating their name with any theatrical productions at all, and they soon faded into memory[33].

Those wishing to view what remains of the Minsky empire today certainly have their work cut out for them: almost all of the old Minsky theaters have been moved, renamed, or torn down since 1937, with the only one that still exists in its original location being the Republic, now named the New Victory. Though it is no longer possible to physically see what a Minsky show would have looked like in its heyday, it is still possible to know a great deal about the experience thanks to both contemporary accounts and later recollections.

Say that you have chosen to attend a show at the Republic Theater sometime in the early 1930s. For one thing, you probably would have known about the show well in advance; publicity stunts, contests, and free passes were frequently used to bring in patrons, with Morton Minsky even claiming that he and his brothers invented the “two-for-one” ticket giveaway[34]. Just getting to the theater could sometimes be a show in itself, since the sidewalks and alleys of Depression-era Broadway were themselves choked with cheap and dubious forms of entertainment such as freak shows[35]. Once inside the theater itself, an alert patron might catch a glimpse of the “specials” (disguised theater employees) or warning lights that were commonly used to thwart police raids on burlesque houses[36]. In addition, you would also probably encounter one or more “candy butchers,” vendors who were permitted by the Minskys to sell candy inside the theater to patrons in exchange for a percentage of their sales income[37].

The shows themselves consisted of a variety of acts, including comedians, strippers, “legitimate” dance acts, and male singers known as “tit serenaders” who performed before or during strip acts[38]. Shows in Minsky theaters generally ran from August to June of each year, with a new program each week[39]. “New,” however, was a relative term, as most shows consisted of comedy material that was either already decades old or had been stolen from other shows, with Abe Minsky famously declaring in 1937 that, “’Not one new burlesque skit has been written in the last twenty years.’”[40]. Likewise, the dance and strip acts also varied in nature and quality. Some performers preferred to do more traditional dance numbers, while others, such as Margie Hart, were infamous for “working hot,” an industry term that meant dancing wildly and provocatively[41]. A final aspect of variety was added to the shows by the possibility of accidents and unplanned disruptions, such as veteran stripper Georgia Southern nearly being knocked unconscious by a falling ceiling microphone, or comedian Rags Ragland being pursued across the stage by a jilted lover armed with a pistol, although such incidents seem to have been rare[42].

The audience, like the show itself, was often a mixed bag. On one hand, the Minskys claimed in a 1930 newspaper interview that the audience at the National Winter Garden was at least fifty percent “highbrow,” and Morton Minsky maintained that burlesque patrons were generally respectable individuals[43]. On the other hand, Morton Minsky did acknowledge that audiences occasionally contained a “creep or degenerate,” and tales of patrons drunkenly interrupting comedians or masturbating during strip acts were not uncommon[44]. An alert observer might also catch sight of a transvestite or a homosexual in the audience; one of the criticisms raised against burlesque houses by Mayor La Guardia and other reformers was that they had become popular hangouts for the city’s gay community[45].

If you were lucky enough to be invited backstage at a Minsky establishment, you would find a scene far removed from the well-oiled machine of the show itself. For one the thing, the female dancers, according to Morton Minsky, generally had very little in the way of modesty as a result of their work, and would usually walk around backstage semi-naked without thinking it shameful or odd[46]. Some of them might be relaxing in between shows, while others might be dying their hair (practically a requirement in burlesque), or applying “stage white,” a type of makeup designed to make skin shimmer under stage lights[47]. If some of the dancers or strippers look very young, it might be because they are; women as young as thirteen were known to work in burlesque shows, often using fake birth certificates to avoid trouble with the authorities[48]. In contrast to the dancers, who were almost exclusively young women, the comedians were mostly middle-aged, married men, although there were a few exceptions to this rule[49]. They generally kept on friendly terms with the dancers, and would usually have been seen either practicing routines or mingling with their colleagues, indulging in card games, coffee, alcohol, and marijuana, or just napping between shows[50]. Despite the grueling work and long hours (some burlesque theaters ran three or four shows each day), being in burlesque during this period did have its perks; high-ranking comedians could make up to $250 a week, while some star strippers made up to $2,000 a week[51].

An analysis of contemporary press coverage of the Minsky brothers reveals an interesting pattern of how the Minskys were viewed in their own time. Generally speaking, press coverage of the Minskys became more serious and less derisive the closer one got to New York itself. Out-of-town papers from cities where the Minskys did not do business, such as Chicago or Washington D.C, generally seem to have viewed the Minsky brothers as a bit of a curiosity or a joke on the rare occasions when they were mentioned[52]. Likewise, on the rare occasions when national publications, such as Time magazine, covered the Minskys, it was usually with a markedly irreverent tone, treating them as a local curiosity rather than as serious showmen[53]. In contrast, cities where the Minskys had business interests generally tended to take them much more seriously. The Pittsburgh Courier, for example, devoted at least two articles to the Minskys’ battle with Paul Moss and their failed attempt to revive their fortunes, both written without a hint of sarcasm, irony, or contempt[54]. Nevertheless, by far the most devoted chronicler of the Minskys in the press was the New York Times, which published at least a dozen, if not more, articles on the Minskys between 1922 and 1937. The New York Times treated the actions of the Minskys as seriously as it treated any other show business news, and generally seems to have recorded their tragedies and triumphs with a serious tone befitting respected, if not fully accepted, members of the community[55]. These various newspaper accounts taken together reveal a great deal about how the Minsky brothers were viewed in their own time. While the nation as a whole may have looked on them as a curiosity at best, they were generally treated as respected members of society within their own communities.

All of this is very well and good, you may say, but the Minskys are gone now. What impact, if any, did they have on the course of history? In truth, the legacy of the Minsky brothers is more than meets the eye. For one thing, the Minskys did very much to nurture an entire generation of stars, from comics to actresses. Comedian Phil Silvers, as well as the team of Abbott and Costello, gained their first real measures of fame working for the Minskys in the 1930s[56]. In addition, Gypsy Rose Lee, perhaps the most famous stripper to ever grace a Minsky stage, went on to popularize striptease across the nation, eventually making the striptease into a symbol of America itself[57]. Truly then, the Minskys could refer to their shows as the “’I-knew-them-when-club,’” without much exaggeration[58]. Beyond that, the Minskys also became an important part of New York City’s burgeoning leisure culture, with Minsky shows becoming a popular way for impoverished Depression-era audiences to entertain themselves[59]. Finally, Minsky shows actually helped to keep old vaudeville-style comedy, as well as sexual themes in entertainment, alive during a time when vaudeville was dying out and other forms of popular entertainment, such as movies, were cracking down on suggestive themes[60].

In conclusion, the legacy of the Minsky brothers is powerful, even if it is not readily visible. Though largely forgotten today, the Minskys in their own time enjoyed one of the most meteoric rises in the history of New York City show business, from a single Lower East Side immigrant theater to a citywide chain. They survived the movies, radio, and the Depression, in the process making a major contribution to the city’s new mass leisure culture. And they left America, almost by accident, with some of its most beloved stars. Perhaps it is time to enshrine another name into the pantheon of New York show business luminaries. Next to Ziegfeld and White, should really be the name “Minsky.”

Bibliography

“Burlesque Suit.” Time, May 2, 1932, 32. Accessed 9 October, 2017. http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=cookie,ip,sso&db=edb&AN=54796774&site=eds-live&authtype=sso&custid=s8475574.

“Burlesque with a Ph.D.: Those Up and Coming Entrepreneurs, the Brothers Minsky, Finally Tell All.” The New York Times, September 7, 1930, sec. Arts & Leisure. Accessed 9 October, 2017. https://search.proquest.com/docview/98841310/abstract/1EA447A43F164A06PQ/20.

“Burlesques at the Park: Minsky Brothers Bring Their Music Hall Entertainment Uptown.” The New York Times, September 16, 1922, sec. Amusements, Hotels and Restaurants. Accessed 9 October, 2017. https://search.proquest.com/docview/100145225/citation/1EA447A43F164A06PQ/4.

Edwards, Willard. “Herb and Mort Wax Patriotic on Strip Tease: Congress Learns About Strip Tease.” Chicago Daily Tribune, February 25, 1937. Accessed 9 October, 2017. https://search.proquest.com/docview/181813757/abstract/275798620A9D42B8PQ/22.

“‘High-Class’ Show of Minsky’s Barred: Moss Refuses License, Holding Brothers ‘Cannot Be Trusted’ to Put on Clean Revue ’Libel’, Is Their Answer ‘We’ll Match Our Private Lives With Commissioner’s,’ They Say, Planning Suit Planned a ‘Variety Revue’ Holds Promise Violated.” The New York Times, June 5, 1937. Accessed 9 October, 2017. https://search.proquest.com/docview/102105025/abstract/1EA447A43F164A06PQ/5.

“M. W. Minsky Dies, Owner of Theaters: Gave Burlesque in the Republic and the Central-Was About to Buy Two More Houses. First Show On Second Av. Took Over the National Winter Garden in Its Moving Picture Days at a 20-Cent Top.” The New York Times, June 13, 1932. Accessed 9 October, 2017. https://search.proquest.com/docview/100556168/citation/275798620A9D42B8PQ/40.

“Minsky Brothers Have Only Frowns For Strip Artists.” The Washington Post, May 6, 1937. Accessed 9 October, 2017. https://search.proquest.com/docview/150865320/abstract/275798620A9D42B8PQ/2.

Minsky, Morton, and Milt Machlin. Minsky’s Burlesque. New York: Arbor House, 1986.

“Minskys Get Writ on Theater Closing: Moss Ordered to Show Cause Why License Should Not Be Issued for Vaudeville.” New York Times, June 12, 1937. Accessed 9 October, 2017. https://search.proquest.com/docview/102211019/abstract/1EA447A43F164A06PQ/11.

“Minskys Reunited After Five-Year Rift: Three Brothers, One of Whom Was Accused of ‘Going Highbrow’ in 1932, Plan New Show.” The New York Times, September 4, 1937. Accessed 9 October, 2017. https://search.proquest.com/docview/102065431/abstract/C3773CA29A644A37PQ/9.

“Old Winter Garden Will Close Tonight: Minsky Brothers to Leave East Side Theater After 18 Years – First Gave Burlesque There.” The New York Times, September 19, 1931, sec. Amusements, Books. Accessed 9 October, 2017. https://search.proquest.com/docview/99287763/abstract/C3773CA29A644A37PQ/6.

Palumbo, Fred. Gypsy Rose Lee. 1956. Photograph. Prints and Photographs Division. Library of Congress. Accessed 4 December, 2017. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Gypsy_Rose_Lee_NYWTS_1.jpg.

Peretti, Burton W. Nightclub City: Politics and Amusement in Manhattan. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2007. EPUB edition. Accessed 9 October, 2017. http://public.eblib.com/choice/publicfullrecord.aspx?p=3442178.

Praefcke, Andreas. New Victory Theatre. May 2007. Photograph. Wikimedia Commons. Accessed 4 December, 2017. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:New_Victory_Theatre_NYC_2007.jpg.

Rowe, Billy. “Broadway Theater to Open for Sepia Revues: Minsky Brothers Get License for Theater Ending Month’s Battle.” The Pittsburgh Courier. June 26, 1937, City edition, sec. Stage, Screen, Drama, Music. Accessed 9 October, 2017. https://search.proquest.com/docview/202016440/abstract/1EA447A43F164A06PQ/8.

———. “Broadway’s All-Sepia Show Closes This Week: Revue Had Opened Wednesday Night to Packed House Bulletin!” The Pittsburgh Courier. July 31, 1937, City edition, sec. Stage, Screen, Drama, Music. Accessed 9 October, 2017. https://search.proquest.com/docview/202044063/abstract/275798620A9D42B8PQ/15.

Shteir, Rachel. Gypsy: The Art of the Tease. New Haven, Connecticut; London: Yale University Press, 2010.

[1] Burton W Peretti, Nightclub City: Politics and Amusement in Manhattan (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2007), EPUB edition, chap. 5. Accessed 9 October 2017. http://public.eblib.com/choice/publicfullrecord.aspx?p=3442178.

[2] Morton Minsky and Milt Machlin, Minsky’s Burlesque (New York: Arbor House, 1986), 19-21.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid., 22-24.

[5] Ibid., 48.

[6] Ibid., 32-33, 48.

[7] Ibid., 43-44.

[8] “Burlesques at the Park: Minsky Brothers Bring Their Music Hall Entertainment Uptown,” The New York Times, September 16, 1922, sec. Amusements, Hotels and Restaurants. Accessed 9 October, 2017. https://search.proquest.com/docview/100145225/citation/1EA447A43F164A06PQ/4.

[9] “Burlesques at the Park”; “Burlesque with a Ph.D.: Those Up and Coming Entrepreneurs, the Brothers Minsky, Finally Tell All,” The New York Times, September 7, 1930, sec. Arts & Leisure. Accessed 9 October, 2017. https://search.proquest.com/docview/98841310/abstract/1EA447A43F164A06PQ/20.

[10] Minsky and Machlin, Minsky’s Burlesque, 58, 61.

[11] Ibid., 61.

[12] Ibid., 68-71.

[13] Ibid., 60. 73, 75.

[14] Ibid., 90-91.

[15] Ibid., 89.

[16] Ibid., 94.

[17] Ibid., 94-95.

[18] Ibid., 97-100.

[19] Ibid., 126.

[20] Ibid., 147.

[21] “Old Winter Garden Will Close Tonight: Minsky Brothers to Leave East Side Theater After 18 Years – First Gave Burlesque There,” The New York Times, September 19, 1931, sec. Amusements, Books. Accessed 9 October, 2017. https://search.proquest.com/docview/99287763/abstract/C3773CA29A644A37PQ/6.

[22] “M. W. Minsky Dies, Owner of Theaters,” The New York Times, June 13, 1932. Accessed 9 October, 2017. https://search.proquest.com/docview/100556168/citation/275798620A9D42B8PQ/40.

[23] Minsky and Machlin, Minsky’s Burlesque, 135-137. The location of the New Gotham is not given due to the possibility that there may have been two theaters of the same name operating simultaneously.

[24] “Minsky’s Reunited After Five-Year Rift: Three Brothers, One of Whom Was Accused of ‘Going Highbrow’ in 1932, Plan New Show,” The New York Times, September 4, 1937. Accessed 9 October, 2017. https://search.proquest.com/docview/102065431/abstract/C3773CA29A644A37PQ/9.

[25] Minsky and Machlin, Minsky’s Burlesque, 135-137.

[26] Peretti, Nightclub City, chap. 7; Minsky and Machlin, Minsky’s Burlesque, 139-141.

[27] Minsky and Machlin, Minsky’s Burlesque, 101, 105-108, 139-141, 273-276.

[28] Ibid., 139-141, 183-185.

[29] Ibid., 257-258.

[30] Ibid., 271-272, 276-280.

[31] “‘High-Class’ Show of Minsky’s Barred,” The New York Times, June 5, 1937. Accessed 9 October, 2017. https://search.proquest.com/docview/102105025/abstract/1EA447A43F164A06PQ/5.

[32] “Minskys Get Writ on Theater Closing: Moss Ordered to Show Cause Why License Should Not Be Issued for Vaudeville,” The New York Times, June 12, 1937. Accessed 9 October, 2017. https://search.proquest.com/docview/102211019/abstract/1EA447A43F164A06PQ/11; Minsky and Machlin, Minsky’s Burlesque, 276-281.

[33] Minsky and Machlin, Minsky’s Burlesque, 280 .

[34] Ibid., 58, 71.

[35] Peretti, Nightclub City, chap. 5.

[36] Minsky and Machlin, Minsky’s Burlesque, 79, 112.

[37] Ibid., 64-67.

[38] “Burlesque with a Ph.D.”; Minsky and Machlin, Minsky’s Burlesque, 97-100, 126-127, 145-146.

[39] “Burlesque with a Ph.D.”

[40] Minsky and Machlin, Minsky’s Burlesque, 41, 252.

[41] Ibid., 153.

[42] Ibid., 160-161, 221-222.

[43] Minsky and Machlin, Minsky’s Burlesque, 141; “Burlesque with a Ph.D.” The Minskys apparently designated patrons as “highbrow” if they lived east of Mott Street.

[44] Minsky and Machlin, Minsky’s Burlesque, 141, 203.

[45] Peretti, Nightclub City, chaps. 5, 7.

[46] Minsky and Machlin, Minsky’s Burlesque, 194-195.

[47] Ibid., 114-115, 197.

[48] Ibid., 123-124.

[49] Ibid., 196-200.

[50] Ibid., 200, 206-208, 234.

[51] Ibid., 127, 197.

[52] Willard Edwards, “Herb and Mort Wax Patriotic on Strip Tease: Congress Learns About Strip Tease,” Chicago Daily Tribune, February 25, 1937. Accessed 9 October, 2017. https://search.proquest.com/docview/181813757/abstract/275798620A9D42B8PQ/22; “Minsky Brothers Have Only Frowns For Strip Artists,” The Washington Post, May 6, 1937. Accessed 9 October, 2017. https://search.proquest.com/docview/150865320/abstract/275798620A9D42B8PQ/2.

[53] “Burlesque Suit,” Time, May 2, 1932, 32. Accessed 9 October, 2017. http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=cookie,ip,sso&db=edb&AN=54796774&site=eds-live&authtype=sso&custid=s8475574.

[54] Billy Rowe, “Broadway’s All-Sepia Show Closes This Week: Revue Had Opened Wednesday Night to Packed House Bulletin!,” The Pittsburgh Courier, July 31, 1937, City edition, sec. Stage, Screen, Drama, Music. Accessed 9 October, 2017. https://search.proquest.com/docview/202044063/abstract/275798620A9D42B8PQ/15; Billy Rowe, “Broadway Theater to Open for Sepia Revues: Minsky Brothers Get License for Theater Ending Month’s Battle,” The Pittsburgh Courier, June 26, 1937, City edition, sec. Stage, Screen, Drama, Music. Accessed 9 October, 2017. https://search.proquest.com/docview/202016440/abstract/1EA447A43F164A06PQ/8.

[55] “M. W. Minsky Dies, Owner of Theaters.”; “Burlesque with a Ph.D.”; “‘High-Class’ Show of Minsky’s Barred.”

[56] Minsky and Machlin, Minsky’s Burlesque, 188, 225-226.

[57] Rachel Shteir, Gypsy: The Art of the Tease (New Haven, Connecticut; London: Yale University Press, 2010), 83-85.

[58] “Burlesque with a Ph.D.”

[59] Minsky and Machlin, Minsky’s Burlesque, 94; Peretti, Nightclub City, chap. 5.

[60] Peretti, Nightclub City, chap. 5.

Gaiety Theater

The former location of the Gaiety Theater. Acquired by Abe Minsky shortly after his split from his surviving brothers in 1932, it became the center of Abe’s attempt to present more “highbrow” entertainment than could be found in typical burlesque shows of the time.

Little Apollo Theater

The approximate former location of the Little Apollo Theater. Not to be confused with the more famous Apollo Theater, this establishment was acquired by the Minskys soon after they left the Park Theater, and quickly became one of their most profitable venues, taking in net profits of around $20,000 a week at its height.

National Winter Garden

The former location of the National Winter Garden. Originally known simply as the National Theater, this was the Minskys’ first theater, and their first foray into burlesque. Originally opened as a combination movie house and vaudeville theater in 1912, the Minskys transformed it into a burlesque house by the end of the decade, and it ...

Oriental Theater

The approximate former location of the Oriental Theater. Acquired by H.K. and Morton Minsky in 1936, it was apparently meant to be a permanent home for Minsky productions, but it was forcibly closed by the city government before this vision could become a reality.

Park Theater

The former location of the Park Theater. Briefly owned by Billy Minsky from 1922 to 1923, the Park represented the Minskys’ first attempt to break out of the Lower East Side and into more “respectable” circles. Low ticket sales, however, forced Billy Minsky to abandon the Park after only about a year.

Republic Theater

The former location of the Republic Theater, now known as the New Victory Theater. The Minskys first acquired this establishment around 1931, and it remained their principal venue until H.K. and Morton moved operations to the Oriental in 1936.