The neighborhood of East Harlem, or “El Barrio”, in New York City has evolved through an ever changing influx of inhabitants. Almost every decade has brought in a new wave of migrants and culture to add to the neighborhood’s anthropological melting pot. Today, it remains one of the most diverse sections of the city, however also one of the most plagued by social issues. Housing, poverty, literacy levels, access to fresh food, over population, and gentrification are just a few of the problems El Barrio is facing. The history of this neighborhood is like a rich tapestry, composed of many people, stories, languages, and cultural contributions that have made it an epicenter of urban life today. In this blog, I am exploring the city through the lens of three different ethnic groups of residents who are portrayed in the novel “Tenants of East Harlem” by author Russell Leigh Sharman. The best representation of a city is its people , and through their elaborate details, stories, and experiences, East Harlem comes alive.

“Located in a somewhat infamous corner of upper Manhattan, East Harlem is hemmed in by 96th and 125th Streets, Fifth Avenue, and the East River. It has always been distinct from the better- known Harlem, at least in the eyes of its inhabitants, though it has not always been considered a specifically Spanish Harlem. Germans, Irish, Italians, Jews, and African Americans all took up residence before the arrival of Puerto Ricans.But currently, Puerto Ricans staked the most recent claim, overwhelming every other ethnic group by sheer numbers so that East Harlem became Spanish Harlem, or El Barrio, which would fight a losing battle with other Harlem for municipal attention and economic development. By the 1980’s and 1990’s East Harlem had become one of the most stigmatized communities in the city. With the introduction of crack cocaine to the informal urban economy, 40 percent became the magic number for East Harlem’s misery: 40 percent of its residents lived below the poverty line, 40 percent of families living there resided in public housing projects; and 40 percent of Harlem households had no wage or salary income.

A decade later East Harlem continues to attract new immigrants who slowly transform the community in the subtle , ongoing work of putting down roots. Mexicans join the well – entrenched Puerto Ricans to radically re align the nationalist divisions of the Latino Community. West Africans along 3rd Avenue confuse notions of African , American, and black. Asians link the urban space in a network of restaurants and bodegas, working behind Plexiglas. And, finally, the gradual appearance of downtown money and upwardly mobile but cash- poor whites signals the latest and most pervasive migration yet.

East Harlem has always suffered the indignities of racial essentialism – the belief that the Italians , the Puerto Ricans , or any other ethnic group was somehow monolithic and usually hardwired for social dysfunction. This idea was often associated with the specific sections of the neighborhood : east of First Avenue was Italian Harlem; south of 110th street was Spanish Harlem. Common sense would suggest that any individual might diverge from the collective stereotype , or indeed that no single individual would match the stereotype at all. And yet, each individual is invariably connected to a particular identity, bound by geography as much as genealogy. Our lives move in and out of the stream of experience that feeds that identity, and each of us, regardless of intention, stands in for the whole. It’s the people that make up East Harlem, that give it a distinct flair, a rich history, and a heartbeat.’ (Sharman 28-29)

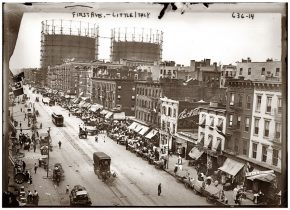

Harlem residents shopping on and enjoying First Avenue, in what they knew as “Little Italy, circa 1940. Photo courtesy of Ms. Angela Gravatar , NYC Italian Geneologist.

Part One : Pleasant Avenue , The Italians

Pete

Pete is an old Italian resident of East Harlem. His parents arrived in NY as husband and wife in the dwindling years of southern Italian migration. Years before their arrival , Italians and European Jews had outpaced the Irish and Germans as dominant immigrant groups. Many of these new arrivals found the Lower East Side already overcrowded and made their way north to East Harlem, known then as Italian Harlem. By 1937 the Mayor’s Committee on City Planning called East Harlem “probably the largest Italian colony in the Western Hemisphere.”

Pete was born in a tenement building on 114th street, the same street he presides over now in his folding lawn chair. His world did not stretch very far beyond 114th Street , Second Avenue and the East River. Work at that time was a scarce commodity. For many immigrants in East Harlem, consistent, gainful employment could be as strange and mysterious an activity.Work was short term and low paying, employing the unskilled for weeks at a time, or more often, days at a time. It was especially difficult for women to to obtain work as well. Many Italian women made their family and home life a full time job.

Housing projects ultimately ushered in the end of the era of Italian Harlem. For Pete, the monolithic housing projects bear the guilt of destroying Italian Harlem and in some ways , perhaps, of killing his parents. Even Pleasant Avenue has lost its hold on Italian Harlem. The neighborhood volved and now was home to Puerto Ricans African Americans Mexicans, Asians, and West Africans.

Young Lords Party march in NYC, circa 1971. Photo courtesy of Máximo Colón , by way of the New York Times.

Part Two : 106th Street , The Puerto Ricans

Jose

Jose is the next interviewee in the book. He is born and raised in East Harlem. He has spent no more than seven years outside of El Barrio. He was born in the 1950’s , and grew up on 104th street. He can remember the feel of the streets around Lexington Avenue and 106th Street before the monoliths of public housing swallowed up the tenements and mass – market consumerism blotted out the local businesses. Migration from his home country of Puerto Rico to the US, and more specifically to East Harlem began in 1910 and continued to thrive the 1970’s. With this wave of immigrants came new faces, language, and practices. One especially prevalent in Jose’s story was Santeria, a religion born in the crucible of Spanish Caribbean Slavery. It derived from Yoruba religion, and was cast by colonizers and social scientists as a form of “folk” Catholicism. It is commonly known as Puerto Rican spiritualism, it seemed to have developed most prominently among the diaspora of New York City.

Similar to Pete’s story, Jose’s childhood life was punctuated by the construction of housing projects. The fear associated with life in an integrated building on the cusp of Italian Harlem subsided as Jose’s family settles deeper into Puerto Rican Harlem.

By the 1960’s, despite the more than half a million Puerto Ricans who arrived in the United States from the island during that decade, the great wave of Puerto Rican migration was slowing. The neighborhood continued to evolve and change, and many residents braced for changes to come. In the summer of 1969, a group known as the “Young Lords”, an outgrowth of the Black Panther movement, had started in Chicago and spread to other cities. In El Barrio specifically, they were protesting the deficiency in municipal attention to East Harlem. As a young active member of his community, Jose found family and common ground within the organization, and worked to change his neighborhood and the perceived policies that were holding his people back in East Harlem. This community work brought together Puerto Ricans and Black in East Harlem, and a played a large part in the next wave of migration to the area.

Part Three : 125th Street, The African Americans

Lucille and Ms. McQueen

In the years following the Civil War, African Americans across the South began to leave and migrate into Northern cities and territories. Historically, this is often referred to as the Great Migration. They followed the demand for labor in Northern Cities like Baltimore, New York City, and Philadelphia. In New York, many migrants flowed into the East Harlem neighborhood. “In just two decades, roughly 200,000 African Americans emigrated from the South to the manufacturing centers of the Northeast and West Coast” (Sharman 81). This caused a huge increase in housing demands and in turn, led to unfortunate methods of discrimination in many neighborhoods. It also led to the creation and rising of housing projects. A area, that Lucille and Ms. McQueen find themselves growing up in. They talk about the heart of the people that lived in these developments, and how drastically they changed they neighborhood of East Harlem. They said it was like a “waterfall of people” flowing into their neighborhood, and with the influx of people came an cultures. They especially liked to listen to then “Puerto Rican tunes at their little bodegas”. (Sharman 92) . They described East Harlem at the times as predominantly African American, with pockets of multiculturalism.The neighborhood was undergoing drastic changes every aspect, and due in part to the work by the Young Lords Party and the Black Panther Party, East Harlem was a place where black American families could find a place and make a life. Racism , inequality, and public discrimination were still alive and well and dominating the American narrative, but in East Harlem, people fought for each other, not with each other. The neighborhood was tough but draped with the stories of resilient people and families, like those of Lucille and Ms. McQueen.

Sources :

Sharman, Russell Leigh. The Tenants of East Harlem. University of California Press, 2006.