The AIDS Crisis in New York City

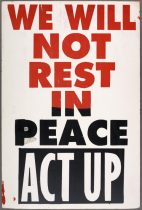

ACT UP City Hall Demonstration

One of the many ACT UP demonstrations, took place on March 28, 1989 at City Hall. It was the biggest AIDS demonstration with 3,000 people protesting Ed Koch’s AIDS policy. D.” ACT UP New York records. Accessed December 05, 2017. http://archives.nypl.org/mss/10#overview.

Saint Vincent’s Catholic Medical Center

This hospital reported one of the very first AIDS cases in the nation. It became one of the primary health centers for AIDS in New York City. Thomas Rzeznik, “The Church and the AIDS Crisis in New York City.” U.S. Catholic Historian 34, no. 1 (2016): 143-65.

Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome, more commonly known as AIDS, first emerged in the United States in the year 1981. Cases of the disease were first reported in Los Angeles and New York when young, previously healthy gay men began developing unusual infections as a result of weak immune systems. Doctors first called the disease Gay-Related Immune Deficiency, also known as GRID. By the following year, 1982, the disease was renamed AIDS by the Center of Disease Control. When AIDS was first discovered there was very little that could be done medically to treat the disease. As a result, people with AIDS were essentially given a death sentence.[1] It was made clear in a New York City Report completed in 1987 that “the consequences of the AIDS epidemic are catastrophic in terms of loss of life and human suffering” and that as the disease continues to spread, “all of the city’s health, social, and human rights services will be severely strained” [2].

The disease hit New York City hard. Out of all the cities in the country, New York had the most reported AIDS cases. By 1983, New York City already had 1,000 reported AIDS cases. In a New York City report done in 1987, it estimated 70,000 New Yorkers had AIDS. This report included that New York accounted for 30 percent of the United States’ AIDS cases. [3] As a result of the majority of people infected with AIDS being homosexual men and little knowledge about the disease, AIDS was given the nickname “gay pneumonia”[4]. As AIDS spread, the public responded with more violence and discrimination towards the gay community. Katy Taylor, a human-rights specialist who worked for the New York City Commission on Human Rights explained that “people are being fired from their jobs, thrown out of their homes, beaten up in their neighborhoods” and that nothing was being done about it because they had “no civil rights”[5]. One example of discrimination towards the gay community was the closing of bathhouses that were known to be frequented by gay men in the city to slow the spread of AIDS by New York City Mayor, Ed Koch[6].

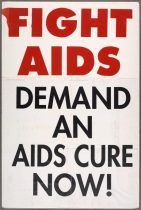

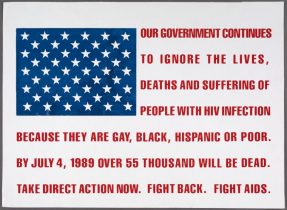

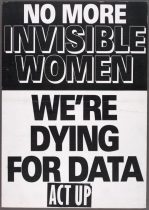

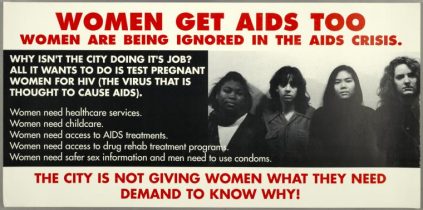

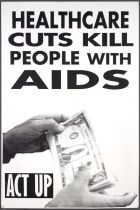

With AIDS impacting a significant number of the gay community, the gay civil rights movement grew with more intensity and power. The priorities of the gay civil rights movement shifted to fighting to change the laws to gain equal rights for members of the gay community. The spread of AIDS “moved the issue of homosexuality and the rights of homosexuals into more open discussion than before”. As AIDS spread throughout the city and country, members of the gay community came together. [7] One group that was founded in March of 1987 in Greenwich Village called the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power, also known as ACT UP, used forms of direct action like demonstrations and civil disobedience all throughout the city to call attention to the severity of the AIDS crisis and the impact it had on those effected by the disease.[8]

Although AIDS was first thought of as a disease that only effected homosexuals, a new group of people, intravenous drug users, were being infected by the disease. This was especially evident in August of 1988 when the number of drug users suffering from AIDS outnumbered the number of homosexual and bisexual men for the first time in New York City. The majority of drug users with AIDS were “concentrated in New York’s inner-city communities” like the South Bronx and Harlem. Communities with high minority populations were at high risk for contracting the virus.[9] In 1987, 36 percent of New York City’s 11,000 reported AIDS cases were intravenous drug users. This percentage was almost double the original percent of intravenous drug user AIDS cases since AIDS was first discovered in 1981. Out of New York City’s estimated 200,000 drug addicts, more than half of them were believed to be infected with AIDS. [10] It is also important to note that “those who have been diagnosed as having AIDS represent only a small fraction of New Yorkers who are infected with the human immunodeficiency virus, or HIV, which is commonly referred to as the AIDS virus”[11]. It was unclear how fast the disease was spreading but one study found that by the year 1989, between one and one and a half million people were suffering from AIDS in New York City[12].

As a result of health care professionals’ lack of knowledge of the disease and the lack of treatment, AIDS “struck a blow in the collective confidence of the medical profession”. As AIDS spread throughout New York City and throughout the country, hospitals and doctors came to the realization that they were “simply unequipped to contend with the brutal realities of the disease, let alone the emotional and spiritual toll it would take on patients and personnel alike”. With the spread of AIDS, medicine and medical providers had to change to care for people suffering from AIDS. “The realities of AIDS forced health care workers to recognize the limitations of medical science and reassess some of the basic tenets of their medical training”. Guenter Risse, a historian, noted that AIDS brought “a rebirth of the caring role” among doctors and other health care providers. This encouraged them to “return to intimate bedside manner and emotional support that had once defined the profession”. [13]

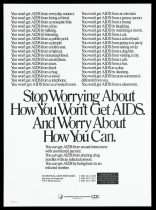

Although it was understood that AIDS was transmitted through the exchange of bodily fluids or through a contaminated needle and syringe by 1987, and was not contagious, the spread of AIDS was still scary[14]. As a result of fear and the unknown, “increasing numbers of women who [were] presumably at low risk [were] seeking to be tested” in New York City. At one of the AIDS testing site on the East Side of Manhattan in April 1987, 40% of the people who wanted to be tested were considered at low risk women. Out of all of these women, none of them tested positive for AIDS. Although none of these women tested positive for the virus that causes AIDS, the large amount of women getting testing was a good thing. Dr. Joseph stated that the “surprisingly high percentage of women at low risk seeking to be tested signified an increasing awareness and concern about AIDS among the city’s heterosexual population”. Susan Rosenthal, the director of AIDS prevention counseling for New York City’s Health Department, also commented on the importance of this turnout. She said it was significant that “women finally began to believe that they could get infected”. Even though at the time the only people considered high risk for contracting AIDS were sexually active homosexuals and intravenous drug users, the health warnings about AIDS were having a positive impact since low risk women were getting tested. [15]

As a result of the New York City report done in 1987, the Mayor of New York, Mayor Koch, proposed an increased AIDS budget for the city. This would include a 98 million dollar increase from 279 million dollars to 385 million dollars in city funds to go towards treatment, testing, counseling, and education for AIDS. Critics like Richard D. Dunne, Executive Director of the Gay Men’s Health Crisis, argued that more money needed to be spent on prevention of the AIDS virus because it would “save the lives and city taxpayers’ money in the future”. [16] Out of the 98 million dollars, only 6 percent of that or 6 million dollars was allocated for AIDS prevention. Many argued that “with little hope for a vaccine or cure for AIDS in the near future, there is only one way to control the spread of AIDS: education”. The majority of the money devoted to stopping the spread of AIDS was not going to prevention and critics argued that “government officials should reevaluate their priorities and commit the vast resources necessary to control this deadly epidemic”. On average, hospital care for an AIDS patient in New York City was about 60,000 dollars. [17]

Not only did the outbreak of AIDS effect present New York City, it also effected the city’s future. Since AIDS was first reported in 1981, 100,000 children were orphaned by AIDS in the United States. Out of the whole nation, New York City was hit the hardest. By 1998, it was estimated that 28,000 New York City children had been orphaned because of AIDS. Experts defined AIDS orphans as children whose mother had died as a result of AIDS since mothers have “historically been considered the primary caretakers of children”. It is important to note that less than 10 percent of these children were infected with the AIDS virus. The Incarnation Center, led by the Catholic Charities of the Archdiocese of New York, is a charity to help children orphaned by AIDS financially. Dr. Stephen Nicholas, the director of the Incarnation Center, said “these children may be New York’s best-kept secret” and that he “can’t think of anyone more needy than them”. By 2001, it was estimated by a study done in 1997 that 50,000 more New York Children would be orphaned by AIDS. In order to help children who were orphaned by AIDS, groups like Pioneers, a group of 11 mothers living with AIDS, helped parents by providing free legal services so parents can draft a will, select a guardian for their children, and assign a medical proxy to make their medical decisions when they are not able to. Groups like these stressed the importance of planning ahead. Russelle Miller-Hill, a member of the Pioneers and a mother of two, stressed the importance of telling your children about your disease and said “they miss out on a lot if you don’t, and you spend so much energy hiding what you could be sharing”. [18]

[1] Thomas Rzeznik, “The Church and the AIDS Crisis in New York City.” U.S. Catholic Historian 34, no. 1 (2016): 143-65.

[2] Tom Boasberg, “New York Must Spend More on AIDS Education: The only way to control the spread of the disease.” New York Times, 1987.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Jonathan Soffer, “AIDS.” In Ed Koch and the Rebuilding of New York City, 305-16. Columbia University Press, 2010.

[5] Richard Meislin, “AIDS Said to Increase Bias Against Homosexuals.” New York Times, 1986.

[6] Jonathan Soffer, “AIDS.” In Ed Koch and the Rebuilding of New York City, 305-16. Columbia University Press, 2010.

[7] Richard Meislin, “AIDS Said to Increase Bias Against Homosexuals.” New York Times, 1986.

[8] “ACT UP New York records 1969, 1982-1997 [bulk 1987-1995] D.” ACT UP New York records. Accessed December 05, 2017. http://archives.nypl.org/mss/10#overview.

[9] Ernest Drucker, “Communities at Risk: The Social Epidemiology of AIDS in New York City.” In AIDS and the Social Sciences: Common Threads, 45-63. University Press of Kentucky, 1991.

[10] Ronald Sullivan, “More Women Are Seeking Test for AIDS: Serious Health Concern Shown by New Yorkers Rise in Women Seeking to Take The AIDS Test.” New York Times, 1987.

[11] Bruce Lambert, “Koch Proposes Rise in AIDS Spending,” New York Times, 1987.

[12] Thomas Rzeznik, “The Church and the AIDS Crisis in New York City.” U.S. Catholic Historian 34, no. 1 (2016): 143-65.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Jonathan Soffer, “AIDS.” In Ed Koch and the Rebuilding of New York City, 305-16. Columbia University Press, 2010.

[15] Ronald Sullivan, “More Women Are Seeking Test for AIDS: Serious Health Concern Shown by New Yorkers Rise in Women Seeking to Take The AIDS Test.” New York Times, 1987.

[16] Bruce Lambert, “Koch Proposes Rise in AIDS Spending,” New York Times, 1987.

[17] Tom Boasberg, “New York Must Spend More on AIDS Education: The only way to control the spread of the disease.” New York Times, 1987.

[18] Adam Gershenson, “Orphaned By AIDS: Giving Solace to Children Made Orphans by AIDS The Neediest Cases.” New York Times, 1998.

Bibliography

“ACT UP New York records 1969, 1982-1997 [bulk 1987-1995] D.” ACT UP New York

records. Accessed December 05, 2017. http://archives.nypl.org/mss/10#overview.

Boasberg, Tom. “New York Must Spend More on AIDS Education: The only way to control

the spread of the disease.” New York Times, 1987.

Drucker, Ernest. “Communities at Risk: The Social Epidemiology of AIDS in New York City.”

In AIDS and the Social Sciences: Common Threads, 45-63. University Press of Kentucky, 1991.

Gershenson, Adam. “Orphaned By AIDS: Giving Solace to Children Made Orphans by AIDS

The Neediest Cases.” New York Times, 1998.

Lambert, Bruce. “Koch Proposes Rise in AIDS Spending,” New York Times, 1987.

Meislin, Richard. “AIDS Said to Increase Bias Against Homosexuals.” New York Times, 1986.

Rzeznik, Thomas F. “The Church and the AIDS Crisis in New York City.” U.S. Catholic

Historian 34, no. 1 (2016): 143-65.

Soffer, Jonathan. “AIDS.” In Ed Koch and the Rebuilding of New York City, 305-16. Columbia

University Press, 2010.

Sullivan, Ronald. “More Women Are Seeking Test for AIDS: Serious Health Concern Shown

by New Yorkers Rise in Women Seeking to Take The AIDS Test.” New York Times, 1987.