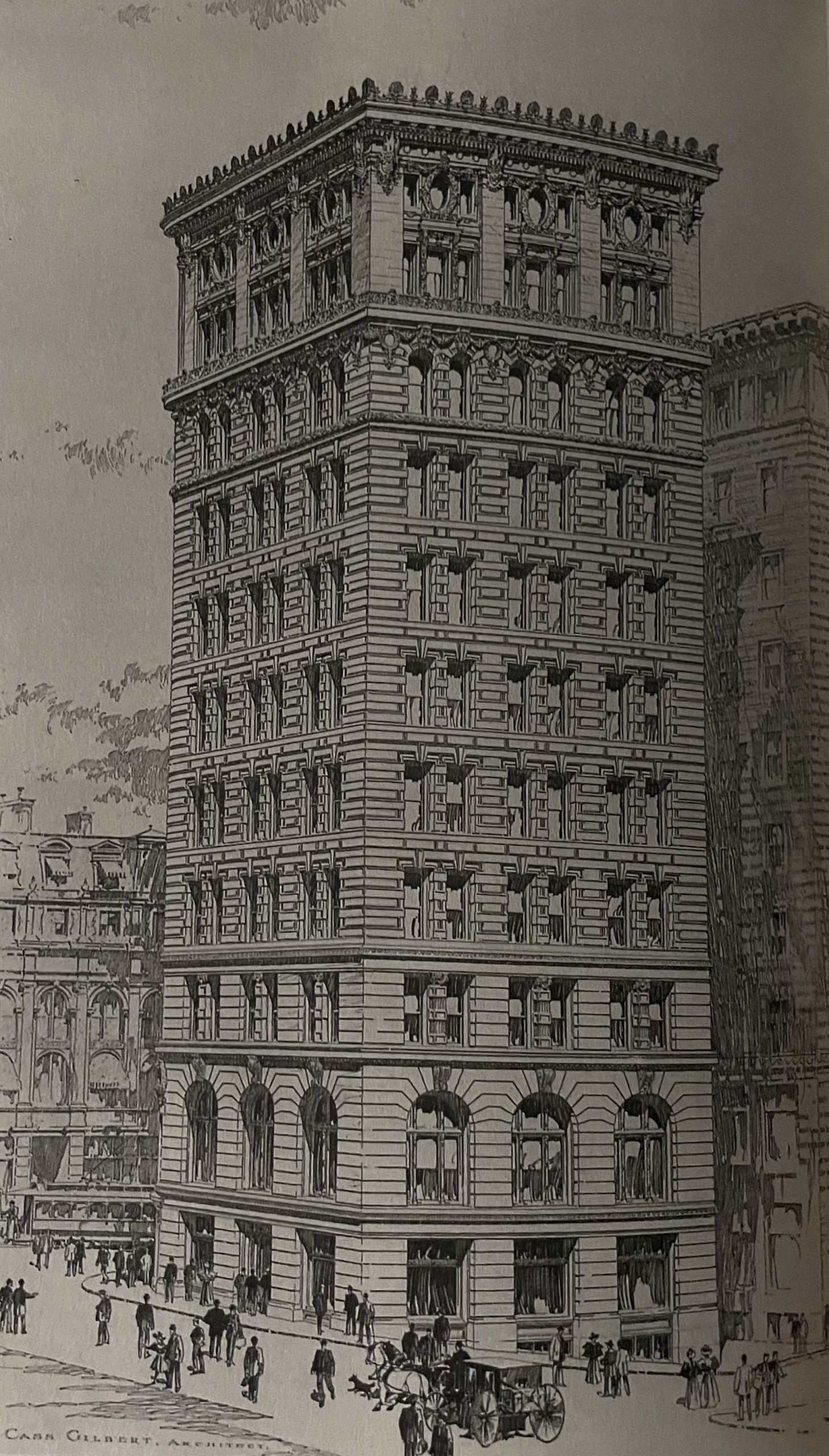

The Woolworth Building is one of the most iconic structures in the New York City skyline. Completed in 1913, it stood as the flagship headquarters of the F.W. Woolworth Company. The gothic features of the building are instantly recognizable and the building stands as a reminder of the of the early years of the skyscraper. Designed by ambitious architect, Cass Gilbert, the building was the tallest in the world at the time of its completion. The company, named after its owner Frank Winfield Woolworth, revolutionized the idea of a department store.

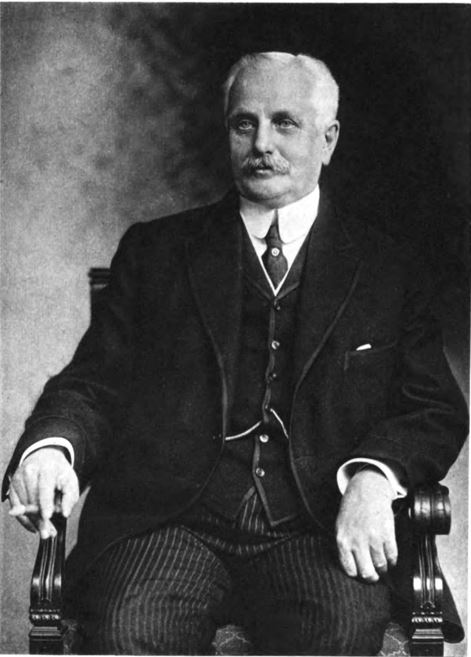

Frank Winfield Woolworth was born on April 13th, 1852, in a cottage that his father had rented from his own father, Jasper Woolworth, in Rodman, New York[1]. At the age of 70, Jasper Woolworth had decided to retire from the farming business, which forced his son to move on from the rented cottage and to search for a new job, which he found in purchasing 103 acres of land in Great Bend, New York, here he would work the land with his children Frank and Charles, selling firewood and potatoes to pay off the $1,600 mortgage, at a payment of $56 two times a year[2]. The idea for Frank Woolworth’s department store was born out of a trip that Frank and his brother Charles took with their father in the Fall of 1862. The boys were shopping for a gift for their mother’s 33rd birthday and were perusing through a dry-goods store when they decided they would buy a set of imitation tortoise-shell combs, the price, 50 cents. The brothers had just five between the two of them, the clerk shooed the children from the store[3]. It was sitting on the curb where Frank Winfield Woolworth laid out his plan to his brother, “One day I’m going to have a store, and nothing will ever cost more than five pennies, and everybody can touch anything they like”[4]. The idea was radical for the time, most stores looked down upon window shoppers and prices were open for bartering, so the five-cent model must have seemed like a fantasy.

The idea of what we now know as a “department” store was not an entirely new one, stores where all types of goods were sold originated in Europe, and a charter for one was written as early as the year 493 in Italy[5]. At the time Woolworth first shared his department store idea with his brother, French entrepreneur Aristide Boucicaut was working to create the first modern department store overseas, with all items available to touch and labeled with a non-negotiable price tag[6].

What set Woolworth apart from the rest of his competitors in the department store business was his shrewd business tactics and his commitment to always finding a way to cut costs. In February of 1912, after years of operating his department stores independently, in an attempt to corner the market and drive costs down, Woolworth sought to create a partnership between himself and five other department store tycoons including his cousin, Seymour Knox, his brother Charles Woolworth, Earle Charlton, Fred Kirby, and William Moore[7]. At the time of the merger, Frank Woolworth owned independently over 300 department stores in the United States, Canada and England, with a total of $15,962,007 in assets, more than any of the other five partners combined[8]

There were worries among the partners that the newly enacted Sherman Anti-Trust act would break up the conglomerate, as it did the Standard Oil Company and the American Tobacco Company, but Frank Woolworth insisted that they would be spared from trust busting because, “The trusts force prices up with tariffs and every other trick; we force prices down for everybody’s benefit.”[9] And indeed the conglomerate did just that. In agreeing to merge, the six partners were able to have enormous negotiating power with manufacturers, forcing the price of goods down, and assuring that the five and dime price would stay as advertised.

Woolworth believed that his work in the department store business was work that served the masses. He lived up to the promise of creating a store that the working man could enjoy. He once stated to one of his employees, “Did it ever occur to you, that our business is an indirect charity and of benefit to the people at large? While we are in business for profit, we are also the means of making thousands of people happy. The more stores we create, the more good we do for humanity.”[10] Woolworth had worked himself up from a farmer to a millionaire, but he had never turned his back on the consumer. His respect for the average man set him apart from the tycoons of the time that held residences on millionaires’ row. His mission to create department stores that gave consumers the best bargain was his ultimate genius, as the country worked its way toward economic and global power in the early 1900s. Much of the United States prior to 1900 was based on a subsistence economy, while after the turn of the century it moved toward a consumer economy, and nothing would define that more than the department store.

When Gilbert was commissioned to design the Woolworth Building, the idea of what a skyscraper was and could be was changing. In New York, there was an intense fascination with building taller and more complex skyscrapers, pushing the limits of what engineering could do, and Gilbert himself sought to experiment with the gothic style[17]. Woolworth requested of Gilbert that the office building be theatrical, striking and magnificent, and to deliver, Gilbert would have to deviate from the contemporary rules of constructing a commercial building. At the time, architect George Hill had laid out standards for how to build an office building that would maximize profit for the building owner, he settled on a height between 16 and 25 stories, and declared that anything taller than this would cost far too much for the profits to be gained[18]. Gilbert and Woolworth initially agreed upon a height of 420 feet, with 30 stories, but within weeks of beginning construction the design had changed to 55 stories and a total height of 750 feet. This height was unprecedented, along with this change, Woolworth also wanted to create an astounding interior for the building that would include public spaces throughout that would be available for the office community. This included a health club with a Turkish bath, a swimming pool, a barbershop, safe deposit vaults, and direct access to the IRT and BRT subway lines[19]. Woolworth’s goal was to wow potential tenants into moving out of his competitors’ buildings and into his newly constructed skyscraper, and the goal was achieved, when the law firm Beach and Pierson moved from the Singer Tower into the Woolworth building[20].

Shortly after the building was completed, President Woodrow Wilson pressed a button on his desk to light up the new Woolworth Building, onlookers were stunned with the sight of the world’s tallest building[23].

The contemporary reviews of the Woolworth Building were quite positive, Addington Bruce, a journalist at the time wrote, “The view from the top of the Woolworth Tower is without question the most remarkable, if not the most wonderful in the world.”[24] The Woolworth Building stood at a towering height of 792 feet, surpassing the Metropolitan Life Insurance Tower by 80 feet[25]. The race for the tallest building in the world was over, for now.

[1] James Brough, The Woolworths (Toronto: McGraw-Hill, 1982), 26.

[2] Ibid. 27.

[3] Ibid. 27.

[4] Ibid. 27.

[5] Ibid. 33.

[6] Ibid. 30.

[7] Ibid. 5-6.

[8] Ibid. 6.

[9] Ibid. 9.

[10] Ibid. 21.

[11] Woolworth, F. W. (Frank W. 1852-1919. (1913). Dinner given to Cass Gilbert, architect. New York : [s.n.].

[12] Gilbert, Cass, and Margaret Heilbrun. Inventing the Skyline: The Architecture of Cass Gilbert. New York: Columbia University Press, 2000. 232.

[13] Ibid. 232.

[14] Ibid.237.

[15] Ibid. 236.

[16] Ibid. 252.

[17] Ibid. 257.

[18] Ibid. 258.

[19] Ibid. 260.

[20] Ibid. 266.

[21] “The Largest Building in the World.” Frank Leslie’s Weekly, 22 June 1911.

[22] Gilbert, Cass, and Margaret Heilbrun. Inventing the Skyline: The Architecture of Cass Gilbert. New York: Columbia University Press, 2000. 266.

[23] Murphy, Kevin D. “The Woolworth Building on the Drafting Board.” Magazine Antiques 185, no. 1 (January 2018): 68–70. https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=sso&db=fth&AN=127362687&site=eds-live.

[24] Bruce, H. A. (Henry A. 1874. (1913). Above the clouds and old New York : an historical sketch of the site and a description of the many wonders of the Woolworth Building. Baltimore : Munder-Thomsen Press. 32.

[25] Ibid. 32.

Bibliography

Brough, J. (1982). The Woolworths. McGraw-Hill.

Bruce, H. A. (Henry A. 1874. (1913). Above the clouds and old New York : an historical sketch of the site and a description of the many wonders of the Woolworth Building. Baltimore : Munder-Thomsen Press.

Gilbert, Cass, and Margaret Heilbrun. Inventing the Skyline: The Architecture of Cass Gilbert.

Columbia University Press, 2000.

Murphy, K. D. (2018). The Woolworth Building on the drafting board. Magazine Antiques, 185(1), 68–70.

“The Largest Building in the World.” Frank Leslie’s Weekly, 22 June 1911.

Woolworth, F. W. (Frank W. 1852-1919. (1913). Dinner given to Cass Gilbert, architect. New York : [s.n.].