Introduction

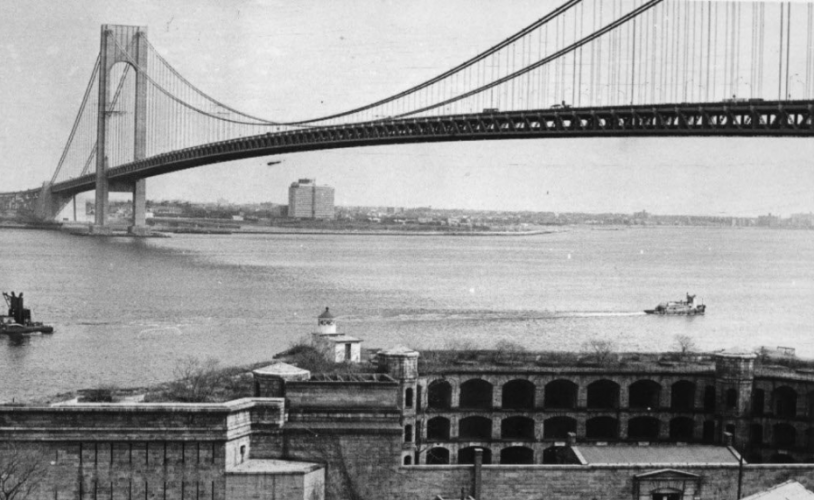

The Verrazzano-Narrows Bridge is a double-decked suspension bridge designed by structural engineer, Othmar Hermann Ammann and urban planner, Robert Moses, that connects the New York City boroughs: Staten Island and Brooklyn.[1] Construction of the Verrazzano bridge began August 13, 1959, and was completed on November 21, 1964, at a cost of $ 320 million ($2.6 billion in today’s dollars). Ibid. The bridge is named after Giovanni de Verrazzano, who was the first European explorer to sail the New York Harbor in 1524. The Verrazzano-Narrows Bridge is currently the longest suspension bridge in the United States with a length of 4,260 feet long, and at the time of completion, it was the longest in the world. [2]

Naming

The naming of the bridge has been a long time coming. Originally, in the planning stages, it was going to be named the Narrows Bridge, as it crosses the Narrows Strait. Then in 1958, Governor Harriman proposed the bridge to be named after the explorer Giovanni de Verrazzano. However, Harriman’s successor, Governor Rockefeller signed the name into law in 1960, as “Verrazano-Narrows Bridge.” It’s notable to point out that only one “z” was included in the name of the bridge, because Rockefeller believed that they should include the American standard way of spelling his name. This incorrect spelling can even be seen on the bridge’s first construction contracts back in 1959, which is most likely where the misspelling stemmed from.[3] For several years, the bridge’s name was largely ignored by media, such as the newspaper, radio reporters, and new reporters. They would oftentimes refer to the bridge as just the “Narrows Bridge” or the “Brooklyn-Staten Island Bridge.” This was suspected to stem for the discrimination against Italian Americans at the time.[4] After several decades, many people argued that the bridge’s spelling should be corrected, and the first attempt to change the name was a petition made by Robert Nash in June 2016. The name change was supported by New York State Senators Martin Golden and Andrew Lanza, who then wrote letters to Thomas Prendergast, who was CEO of Metropolitan Transportation Authority. A bill had been drafted and delayed in 2017, and another was created in 2018, where members of the Senate unanimously passed a bill regarding a name change, which was sent to Governor Andrew Cuomo for approval. Hesitation regarding the renaming of the bridge was largely due to the price tag this change would bring. It would be projected to cost $350,000 to modify dozens of signs. In order to save money, New York would leave the existing signs with the single “z,” and have all new signs contain the double “z” spelling. Finally, on October 1st, 2018, Governor Cuomo signed the bill, officially changing the name of the bridge to “The Verrazzano-Narrows Bridge.” [5]

Early Stages

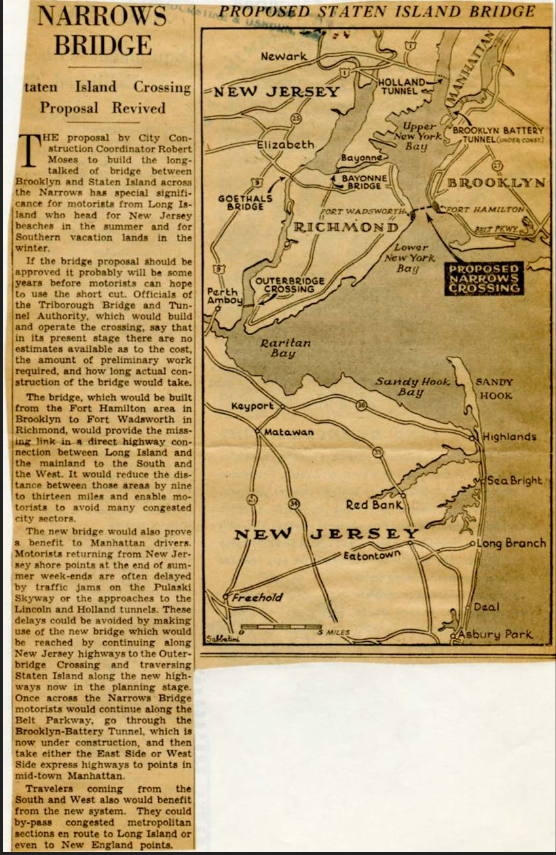

The idea for the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge originally started as an idea to build a connection between the two boroughs using a tunnel system. The idea for such a system had dated back to 1888 and emerged as a way to connect the isolated borough of Staten Island, which had only been connected by ferry at the time. There had been several attempts to get the tunnel project going, in 1923, 1927, and 1937, which had all been discontinued due to the high cost of excavation.[6] Eventually, the idea for a bridge to connect the two boroughs instead of a tunnel had gained traction in 1949, when the project became approved. The chairman of the Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority granted approval for its construction because he wanted a way to connect some of the other city’s thoroughfares: these being the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway, the Staten Island Expressway, and the Belt Parkway. The switch to building a bridge was primarily due to the fact that it would be cheaper and faster to construct, and a bridge would be able to support a higher traffic volume than a tunnel. Unfortunately, the project continued to get delayed for several years due to lack of funding until 1959, when the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey began financing the project. Ibid. Surveying of work for the bridge was conducted in January of 1959, and the displacement of 7,000 residents in the Bay Ridge neighborhood ensued. This was extremely controversial, as this wasn’t the first time one of Robert Moses’ projects to improve the city had displaced thousands of New Yorkers. Eventually, 800 homes had been demolished and on August 14th, 1959, construction of the bridge began. Ibid.

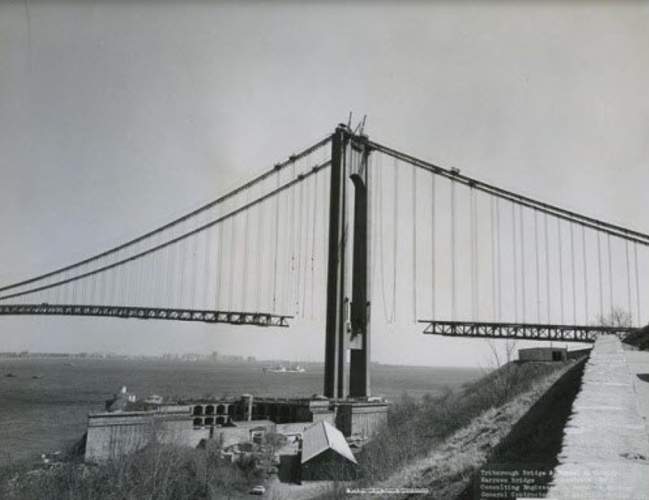

The construction of the bridge began with the development of steel and concrete anchorages on both ends of the Narrows, which would be needed in order to hold up the cables of the bridge.[8] Then, in order to keep this project within the time budget, each of the towers’ construction was completed by different construction companies; Bethlehem Steel built the Staten Island tower, and the Harris Structural Company built the Brooklyn tower.[9] The towers were constructed in three parts and brought to the construction site by flat-bottomed boats called barges, to be installed. Each of these sections was lifted by a lifting device called a derrick, which were positioned alongside the tower piers, and placed on top of the anchorages. These sections were then secured together in order to form the towers.[10] When constructing the towers, it’s interesting to note that they weren’t built parallel to each other. Both towers were built 1 5/8 inches father apart at their peak than their base, in order to compensate for the curvature of the earth.[11]

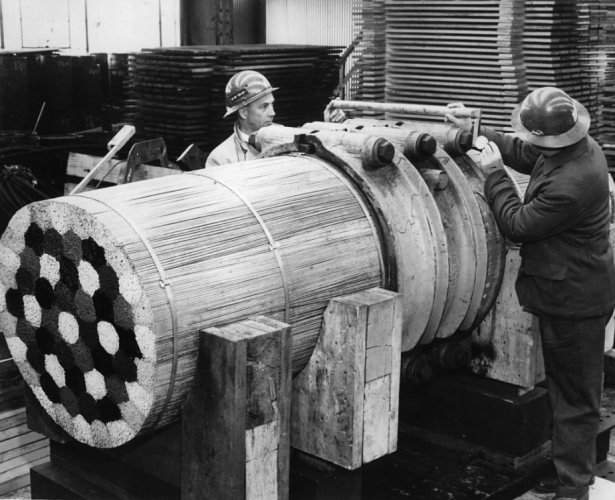

Once the 693-foot towers were built, the cables to hold up the bridge needed to be spun, which began in March of 1963. This process was the most time consuming and costly part of the construction of the bridge, considering 142,520 miles of bridge cables had to be strung 104,432 times around the bridge. The fabrication of the cables was done by using wheels to spin the wire back and forth, from one end of the bridge to the other. The spinning of the wheels lasted nearly six months, running day and night. As the 428 wires had spun through the wheel, workers would grab the wire as it would pass through and clamp them together, which would form a singular strand. 61 of these strands would then be hydraulically pressed and encased in steel. Once all four main cables were fabricated, the 262 steel suspender ropes that were prefabricated off-site, were attached to the main cables. Once the suspension cables were installed, it was time to install the bridge decks.[12]

Workers and Conditions

Over the course of the five-year construction period, over 10,000 workers were employed, with about an average of 1,200 workers helping construct each day.[18] Many of these men who worked at the construction site utilized catwalks, which are mesh roadways that were hooked to each tower and were made to work with no harnesses. This was a major safety concern that become a real issue when a 19-year-old catwalk worker, named Gerard McKee, had slipped on the catwalk, and fallen to his death on October 9th, 1963. This incident was not the first death; however, it sparked a five-day strike on December 2nd, 1963, in which workers demanded safety nets. The nets were granted, and after the installation, went on to save three other ironworkers who had fallen. Two other workers had died prior to the installation of the nets. The first man was 58-year-old Paul Bassett, who had fallen inside the Brooklyn tower on August 24th, 1962. The second man was 58-year-old Irving Rubin, who fell off an approach and died because of his injuries on July 13th, 1963.[19] Over the entire course of construction, there was a total of three men who had died, and three others that had fallen, but were saved by the nets. After the completion of the bridge, none of the 12,000 workers who helped construct the bridge were invited by Robert Moses to the opening ceremony, so they then boycotted the event and attended a mass in memory of the three workers who had passed during the construction of the bridge. Ibid.

Several new construction initiatives have been made since the initial opening in 1964. For starters, the construction of the bridge’s lower deck. Originally, the bridge was opened as a six-lane roadway, with the capacity and potential to have more, because of the lower deck. A second deck wasn’t projected to be needed until around 1978, but the growing popularity of the bridge proved otherwise. It became clear, that due to the influx of motorists over the next five years, that the lower deck was needed to alleviate high levels of traffic. Construction of the lower deck cost $22 million and was completed on June 28th, 1969, which opened six more lanes.

Another new improvement to the bridge was the introduction of the EZ-Pass in 1995. The intention of the EZ-Pass was to reduce the traffic congestion at tollbooths caused by motorists stopping to pay the toll with cash or tokens. The installation lowered the amount of time to get through the tollbooth from fifteen minutes to thirty seconds. By 2017, cashless tolling had taken over, where all westbound tollbooths were dismantled, and cash tolls were no longer an option. These booths were replaced with cameras and EZ-Pass readers, so motorists can cross the bridge without stopping or slowing down. If a motorist does not have an EZ-Pass, a picture of the license plate is taken, and a bill is mailed to the owner of the vehicle. These improvements make it more efficient to travel across the bridge.[21]

Regarding maintenance and upkeep, the city of New York began a $1.5 billion reconstruction of the bridge in 2014. The first phase of the reconstruction plan was to replace the upper deck with new orthotropic deck sections, as well as removing a divider in order make more room for a seventh lane. This new lane would be opened as a high-occupancy vehicle lane, which is a lane that is only allowed to be driven in if the number of passengers in the car is above two. This is implemented to encourage ridesharing or carpooling in order to reduce traffic on the roads. The phase one construction was completed in 2017 and cost $235 million. The second phase of reconstruction will include replacing the lower deck, however for this construction, the lower deck would need to be closed, which is why the city prioritized the reconstruction of the upper deck first, which added capacity.[22]

Works Cited

Primary Sources:

Talese, Gay (1964). The Bridge: The Building of the Verrazano–Narrows Bridge. New York City: Harper & Row. ISBN 9781620409114.

“Verrazano It Is, in Bridge’s Name; Governor Signs Disputed Designation Into Law”. The New York Times. March 10, 1960. ISSN 0362-4331. Accessed February 25, 2022.

Gonzalez, D., 2014. Falling for the Photo in Staten Island. [online] Lens Blog. Available at: <https://lens.blogs.nytimes.com/2014/07/01/photo-verrazano-bridge-staten-island-brooklyn/> [Accessed 21 February 2022].

Dalton, K., 2015. Vintage Photos of the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge. [online] Silive. Available at: <https://www.silive.com/timecapsule/2015/10/tbt_vintage_photos_of_the_verr.html> [Accessed 21 February 2022].

“Narrows Bridge.” New York Times. 5 October 1947. Available at: <https://www.bklynlibrary.org/sites/default/files/documents/brooklyn-collection/connections/Bridges%20PP.pdf>

Secondary Sources:

CUNY. “NYCDATA: Infrastructure.” NYCdata | Infrastructure, 2021, https://www.baruch.cuny.edu/nycdata/infrastructure/verrazano.html.

Arnold, W., 2009. A Critical Overview of the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge. [online] Citeseerx.ist.psu.edu. Available at: <https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.561.5283&rep=rep1&type=pdf> [Accessed 21 February 2022]

Rastorfer, Darl (2000). Six Bridges: The Legacy of Othmar H. Ammann. Six Bridges: The Legacy of Othmar H. Ammann. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-08047-6.

Adler, J., 2014. The History of the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge, 50 Years After Its Construction. [online] Smithsonian Magazine. Available at: <https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/history-verrazano-narrows-bridge-50-years-after-its-construction-180953032/> [Accessed 21 February 2022]

Barone, Vincent (October 15, 2015). “Decades of construction being planned for Verrazano-Narrows Bridge”. Staten Island Advance. Accessed March 26, 2022.

Gross, Jane (March 25, 1997). “Electronic Tolls Are Catching On, And Commuters Are Catching Up”. The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Accessed March 27, 2022.

Rivoli, Dan (October 1, 2018). “Verrazzano Bridge finally gets name corrected, decades later”. Daily News. New York. Accessed April 2, 2022.

[1] CUNY. “NYCDATA: Infrastructure.” NYCdata | Infrastructure, 2021, https://www.baruch.cuny.edu/nycdata/infrastructure/verrazano.html.

[2] Arnold, W., 2009. A Critical Overview of the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge. [online] Citeseerx.ist.psu.edu. Available at: <https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.561.5283&rep=rep1&type=pdf> [Accessed 21 February 2022]

[3] “Verrazano It Is, in Bridge’s Name; Governor Signs Disputed Designation Into Law”. The New York Times. March 10, 1960. ISSN 0362-4331. Accessed February 25, 2022.

[4] Talese, Gay (1964). The Bridge: The Building of the Verrazano–Narrows Bridge. New York City: Harper & Row. ISBN 9781620409114.

[5] Rivoli, Dan (October 1, 2018). “Verrazzano Bridge finally gets name corrected, decades later”. Daily News. New York. Accessed April 2, 2022.

[6] CUNY. “NYCDATA: Infrastructure.” NYCdata | Infrastructure, 2021, https://www.baruch.cuny.edu/nycdata/infrastructure/verrazano.html.

[7] “Narrows Bridge.” New York Times. 5 October 1947. Available at: <https://www.bklynlibrary.org/sites/default/files/documents/brooklyn-collection/connections/Bridges%20PP.pdf>

[8] Rastorfer, Darl (2000). Six Bridges: The Legacy of Othmar H. Ammann. Six Bridges: The Legacy of Othmar H. Ammann. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-08047-6.

[9] “Verrazano It Is, in Bridge’s Name; Governor Signs Disputed Designation Into Law”. The New York Times. March 10, 1960. ISSN 0362-4331. Accessed February 25, 2022.

[10] Arnold, W., 2009. A Critical Overview of the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge. [online] Citeseerx.ist.psu.edu. Available at: <https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.561.5283&rep=rep1&type=pdf> [Accessed 21 February 2022]

[11] Talese, Gay (1964). The Bridge: The Building of the Verrazano–Narrows Bridge. New York City: Harper & Row. ISBN 9781620409114.

[12] CUNY. “NYCDATA: Infrastructure.” NYCdata | Infrastructure, 2021, https://www.baruch.cuny.edu/nycdata/infrastructure/verrazano.html.

[13] Rastorfer, Darl (2000). Six Bridges: The Legacy of Othmar H. Ammann. Six Bridges: The Legacy of Othmar H. Ammann. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-08047-6.

[14] Talese, Gay (1964). The Bridge: The Building of the Verrazano–Narrows Bridge. New York City: Harper & Row. ISBN 9781620409114.

[15] Dalton, K., 2015. Vintage Photos of the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge. [online] Silive. Available at: <https://www.silive.com/timecapsule/2015/10/tbt_vintage_photos_of_the_verr.html> [Accessed 21 February 2022].

[16] Talese, Gay (1964). The Bridge: The Building of the Verrazano–Narrows Bridge. New York City: Harper & Row. ISBN 9781620409114.

[17] Rastorfer, Darl (2000). Six Bridges: The Legacy of Othmar H. Ammann. Six Bridges: The Legacy of Othmar H. Ammann. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-08047-6.

[18] Adler, J., 2014. The History of the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge, 50 Years After Its Construction. [online] Smithsonian Magazine. Available at: <https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/history-verrazano-narrows-bridge-50-years-after-its-construction-180953032/> [Accessed 21 February 2022]

[19] Talese, Gay (1964). The Bridge: The Building of the Verrazano–Narrows Bridge. New York City: Harper & Row. ISBN 9781620409114.

[20] Rastorfer, Darl (2000). Six Bridges: The Legacy of Othmar H. Ammann. Six Bridges: The Legacy of Othmar H. Ammann. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-08047-6.

[21] Gross, Jane (March 25, 1997). “Electronic Tolls Are Catching On, And Commuters Are Catching Up”. The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Accessed March 27, 2022.

[22] Barone, Vincent (October 15, 2015). “Decades of construction being planned for Verrazano-Narrows Bridge”. Staten Island Advance. Accessed March 26, 2022.