The end of World War I saw America emerge as a global superpower, and there is possibly no greater representation of this than Victory Way. Victory Way was an art exhibit created by the U.S. government in 1919, a few short months after the end of the First World War, lining Park Avenue outside the main entrance to Grand Central Station in Manhattan. The imposing art exhibition, featuring several German weapons and pieces of equipment, was an unignorable presence outside of the busy station. Originally erected as a way to pay back debts from the war, Victory Way’s legacy has become that of American military strength and the United States becoming an unquestionable world power at the end of World War I. While the installation was only present throughout 1919, being taken down later that year, its legacy and purpose have survived into today.

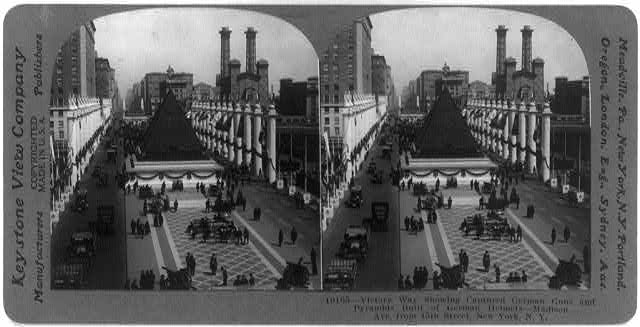

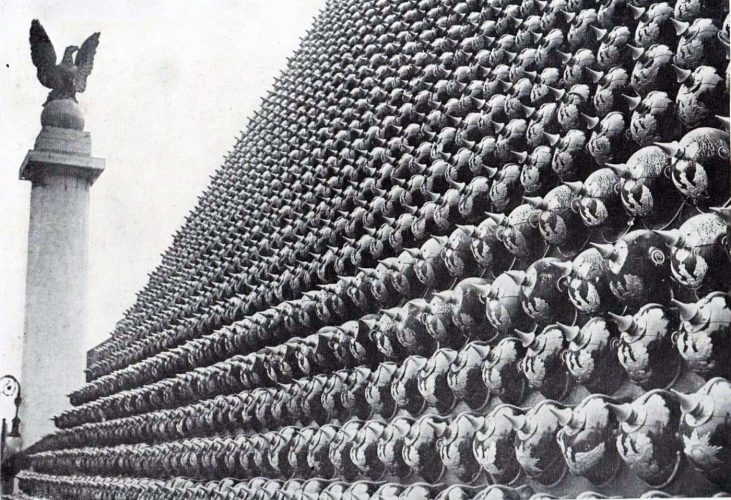

Victory Way was a grand gesture of American power. Pictured below from different angles, the exhibit took up several blocks of Park Avenue, one of New York’s busiest streets. Various pieces of traditional Americana lined the street, such as statues of eagles, ticker tape and banners colored after the American flag, statues of Lady Liberty modelled after the Statue of Liberty itself, and several decorations patterned with patriotic stars. The middle of the road has the main pieces that make up the exhibit. Several captured German weapons line the street, including disabled artillery cannons, unloaded German rifles, and disabled grenades, all organized in orderly bunches. The main part of the exhibit, however, are the German helmets. A handful of pyramids on the street displayed captured German soldier helmets, approximately 12,000 in all, all stacked in order upon the pyramid-shaped bases. As pictured below, the whole area makes quite an impression upon a viewer, but it is also important in the history of New York, as well as the history of America as a whole, as a representative moment in time.

The purpose of this grand display was to pay off debts that America accrued during World War I via war bonds. Though WWI lasted from 1914 to 1918, America only joined the conflict in the latter half of 1917 until its conclusion in the following year. Despite the short time of involvement, the United States saw a handful of major battles near the end of the war and provided a great amount of support to its European allies, including manpower, weapons, vehicles, and other miscellaneous supplies.[1] In order to pay for this war effort, war bonds were used the same way they were in previous wars and would be used in wars to follow. War bonds act as a system of debt for the respective government at war; some cash amount is directly paid to the government by a civilian in order to immediately fund the war effort, and then the civilian is promised some sort of extra compensation once the war has concluded and the country’s economy is back in a proper state. This is often done through loans, as many American war bonds throughout history have promised a better return on investment for the amount given once peace is achieved. Victory Way, however, was different.

Victory Way is a rare example of war bonds being more immediate in nature. How the system worked was that the United States government was, in a sense, selling captured equipment to the highest bidder. The captured German weaponry and helmets were sold through auctions and other means in order to pay back the war debt. Some of the smaller equipment, such as a certain number of helmets and rifles, were sold directly via government merchants stationed near the art exhibit, while the more valuable equipment, such as the artillery pieces and larger batches of supplies, were reserved solely for special auctions held by the U.S. Army.[2] The selling of the equipment was ultimately a success, likely due in no small part to the highly trafficked area that the installation was set up in, as most of the exhibit was sold by the time it was taken down in late 1919, with the leftovers then being sold to private parties via requests. While this is a fascinating piece of American history in and of itself, the symbolism behind Victory Way has taken on a legacy of its own that eclipses its purpose of paying debt.

Victory Way is possibly as heavy-handed in its symbolism as a post-war, government created art piece can be. The tower piles of captured enemy equipment surrounded by dazzling displays of American patriotism leave little room for interpretation. There are, however, some important historical facts which must be taken into consideration regarding this symbolism. Firstly, it is vital to note just where the art installation was displayed. For such a powerful piece of symbolism, it required placement in an equally powerful representation of the United States. However, it is not in the capital of Washington D.C., nor the historically important cities of Boston or Philadelphia, the two cities that were, historically, most associated with the American ideals of liberty and independence, even in this period.[3] The exhibit is housed in the center of New York City, demonstrating an important moment in the city’s history that proclaims, without any doubts, that New York has now become a metropolitan powerhouse of the globe, as well as a universal symbol of the United States. This symbolism was only enhanced by the fact that, throughout Victory Way’s presence in New York throughout 1919, several events were held there, most notably politicians and other influential individuals gave speeches from a pulpit backed by captured German helmets.[4] The message to passersby, as well as the world, was clear: New York was powerful, influential, and distinctly American.

Another important facet to note was that some of the history behind this powerful piece of American symbolism is inaccurate. Incorrect information began to spread, and hence, some future reporting on the topic claimed, that the total number of helmets, 12,000 in all, represented the approximate number of German soldiers killed in WWI by American troops. This figure is unprovable, yet almost definitely incorrect. The approximate number of German military casualties in WWI is around two million, with the number of German troops killed by American soldiers not only baseless, but also undoubtedly much higher than 12,000.

Likewise, there is a minor dishonest implication in the detail of the supplies captured from German soldiers that make up Victory Way. Though never specifically stated, news reports about Victory Way had implications that the supplies were directly captured from German soldiers by Allied soldiers on the frontline. The truth is that while all of the equipment and weapons displayed and sold were indeed captured from Germany, they were secured from German stockpiles and factories. In fact, the iconic helmets used for Victory Way are ‘pickelhauben’, or German spiked helmets used since the mid-19th Century. These helmets were replaced en masse with the introduction of the more protective and easier to produce ‘stahlhelm’ throughout late 1915 and early 1916. This, combined with the clean and undamaged condition the helmets were in, makes it a reasonable assumption that these helmets were more than likely leftovers from a supply room that were replaced before the United States had even officially entered the war, with it being even further removed from any American troops actually seeing combat in Europe.

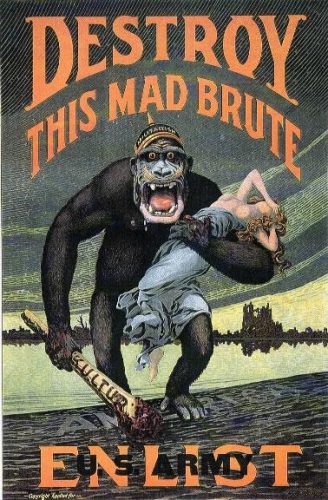

The question then becomes one of how, or why, this implied misinformation was presented as truth. The possible answer lies in propaganda. While Victory Way was, first and foremost, a tool to earn money for the American government, it is also an extremely prominent piece of American military propaganda. This is most obvious when one realizes how symbolic the equipment being displayed is. The German weapons, which had terrorized America’s European allies a mere year before, were captured, disabled, and on display for the world to see. The helmets on display are iconic pieces of imagery of militaristic Germany, as countless propaganda posters, including the famous “Destroy This Mad Brute” poster (pictured below), use the spiked helmets to represent the German war machine.[5] All this, combined with Victory Way’s placement in the populated hub of Manhattan in its most busy area, Grand Central Terminal, shows Victory Way’s purpose as art. Victory Way symbolizes the end of the war and America’s role in it, or at least how the American government wished to portray these events. The German military, which had caused such bloodshed in Europe throughout the war, had been stripped of its fighting spirit and demolished upon the arrival of the American military on the continent. Their weapons of war and representations are then taken and paraded in America’s busiest city for all to see, further humiliating Germany and showing the world the absolute dominance of American might, as was a common theme in art of the period.[6] It is a city block’s worth of patriotism, and one which the American people looked upon with pride.

Victory Way provides not only an interesting bit of history about New York City, but about the 1910s as a whole and America’s place on the world stage. The story it tells provides us with important lessons on propaganda, national politics, military representation, and symbolism in ways both obvious and subtle. Most relevant, however, is the exhibit’s role as a mark of New York’s role within the world during the period. Among all of the United States, the greatest symbol of American might and the end of a global conflict was decided to be placed in the heart of New York City. There is no denying that this, symbolically and logistically, is one of the defining moments throughout history that cemented New York City as not only a metropolitan hub for the United States, but a global city whose actions would affect the globe.

[1] Matthias Strohn. World War I Companion, 195-210.

[2] Aaron Noble. A Spirit of Sacrifice, Pg. 287.

[3] “A.E.F. Honored in Washington.” The Funstonian, 1919.

[4] “Marine Day Spurs Sales.” New York Times, 1919.

[5] Hopps, Harry R. Destroy This Mad Brute, 1918.

[6] Naves, Mario. World War I and the Visual Arts, 2017.