New York City’s Randall’s Island is a destination not only for New Yorkers, but for travelers far and wide. Located in the city’s East River, Randall’s Island is known today as an entertainment haven, complete with athletic fields, driving ranges, and concert venues. Additionally, the island is a transportation hub, hosting the Robert F. Kennedy, previously known as the Triborough, Bridge. This bridge, which is actually a system of 3 separate bridges, connect Manhattan, Queens, and the Bronx, using Randall’s Island as the point of junction. All of these modern purposes, as well as the uses of the past, have helped shape Randall’s Island into a critical piece of New York City’s history and infrastructure.

The story of Randall’s Island begins quite early; so early, in fact, that it comes very shortly after the beginning of Dutch settlement of Manhattan in 1624.[1] In 1637, the Dutch purchased Minnahanonck, Randall’s Island, and Tenkenas, Wards Island, from the Lenape in order to develop more farming land. The resulting purchases were renamed to Little Barn Island and Big Barn Island, respectively.[2] This was the first public purchase of the islands, a trend that would not continue again for some time. After the purchase, the islands maintained the function of farming and other natural purposes, such as housing the rock quarry for the Old Trinity Church.[3] The first private purchase of the islands came in 1772, with Captain John Montresor of the British Military purchasing and renaming Little Barn Island after himself. The newly minted Montresor’s Island became his settlement until the Revolutionary War began, when it was used by the British to launch attacks on Manhattan until their evacuation in 1783.[4] Montresor used the island to analyze the city for points of invasion prior to the war, and throughout the war’s timeframe, he turned the island into an officers’ hospital. Also to note, Big Barn Island became a military base during the war, establishing an active military role for both islands during the Revolutionary War.[5]

The next private purchase of Randall’s Island came in 1784, when it was purchased by Jonathan Randel, whom it is still named after today despite the slight spelling difference, a mistake by the city.[6] Randall’s Island remained in the Randel family until 1835, when it was purchased by the City of New York for 60,000 dollars.[7] The city purchased Wards Island soon after, in 1851, and together they served a number of public functions.[8] This purchase marked the end of private ownership of Randall’s Island, which quickly began being used for a wide variety of public functions, such as the relocation of Manhattan potter’s fields and the construction of various institutions. Randall’s Island was made home of an orphanage, children’s hospital, and a reform school called The House of Refuge. The House of Refuge was intended to incarcerate teenage criminals, mainly Irish, where they spent part of their day in religious and school-curriculum based classes, and the other part of their day performing lucrative labor for the state. The conditions were not ideal, as the boys were forced to perform this labor for outside contractors, and those who misbehaved were punished. It wasn’t until 1887, when the labor from residents no longer became lucrative, that conditions somewhat improved.[9]

Meanwhile, Wards Island was mainly used as a relocation site for Manhattan potters fields, which were becoming overwhelmed due to the rapidly rising population and length of settlement. Starting in 1840, nearly 100,000 bodies were moved from the Madison Square Park and Bryant Park potter’s fields, finding a new location in the southern tip of Wards Island.[10] In addition to assisting in the relocation of the potters fields, Wards Island was also home to the State Emigrant Refuge, a hospital for “sick and destitute immigrants”, one of the largest hospital complexes in the world during the 1850s.[11] These rededication of the use of Randall’s and Wards Islands was not unique, and in fact, can be seen as a small example of greater New York City trends. The city had become one with a rapidly growing population and an even quicker growing issue of separated wealth. The wealthy were growing richer, and the poor poorer, causing the city to begin trying to separate the suffering from the successful. By relocating the potters fields and the treatment facilities for the City’s less fortunate citizens to a separate island, the city was physically putting distance between itself and some of its major issues, a trend that would often continue in the future.

Through the latter half of the 19th century, Randall’s Island continued to grow in its public services. In addition to the aforementioned House of Refuge, the island also became home to the Idiot Asylum, a homeopathic hospital, the Inebriate Asylum, and the City Insane Asylum, further solidifying the trend of segregation of its “undesirable” residents.[12] The island had grown from a small farming island, to a private residence, to an important wartime location, to an area of suffering under the name of “public service”. The purchase of both Randall’s and Wards Islands allowed the city to have a water-based separation between its main population and the less savory side of urban life, such as proper burial grounds and dealing with those less fortunate. The city now had the ability to physically separate itself from many issues, highlighting a dark time both in the history of Randall’s Island and the City of New York as a whole.

The turn of the 20th century marked a time of great transformation for Randall’s and Wards Islands. From this point forward, the islands would cease being a place for the city to dispose of issues, but rather, a place for the city to grow. The city began to realize the value of the location of the islands, and started to work on making them more connected both to each other and the rest of the city. Construction began in September 1916, on the Hell Gate Bridge and railroad trestle. This connected both islands, as well as Queens and the South Bronx.[13] Soon after that, in 1929, the city began construction on the 17-mile Triborough Bridge. The islands began to be significantly more connected to the rest of the city, beginning their transition into their greater roles to serve not just the city’s problems, but also its needs and wants.

The year 1930 marked one of the greatest changes in the history of Randall’s and Wards Islands since their purchase by the city, as this was the year the Metropolitan Conference on Parks recommended the islands have all of their institutions removed. With their removal, the islands were left, instead, with a more recreational focus.[14] The city acted on the recommendation in 1933, officially transferring ownership of the islands to the Department of Parks and Recreation, which immediately began working to transform Randall’s Island to parkland. In 1935, the Department evacuated the children’s hospital and demolished the House of Refuge, putting an end to the island’s time housing this line of work. From this point forward, recreation and transportation become the main purpose of the islands.[15] Over the following years, the islands begin to see the construction of numerous fields and tennis courts, as well as the construction of Triborough Stadium. In 1936, the Triborough Bridge and Triborough stadium opened, hosting the Olympic track and field trials. Interestingly, it was at this event that Jesse Owens qualified for the 1936 Berlin Olympics.[16]

Following the theme of connectivity, the Randall’s Island did continue to expand in both its connections and service to the rest of the city. In 1937, a sewage treatment plant opened on Wards Island, servicing the city’s waste in a safer manner more removed from the main boroughs. Additionally, in 1951, the Wards Island Pedestrian Bridge opened, providing Manhattan residents with significantly easier access to the parks on both islands.[17] It was also around this time that the area in between the two islands was turned into a landfill, finally physically connecting them for the future under the name of Randall’s Island.

As time passed, the Randall’s Island continued to expand in the realm of recreation, hosting music festivals and concerts for the masses. Spanning from the 1970s to present day, the biggest names in music and entertainment held concerts and events on the island, drawing New Yorkers to the parks for various forms of entertainment. In the most recent updates to the island, Downing Stadium, the original sporting stadium, was demolished in 2003 to create the new Icahn Stadium, and in the same year, a ferry dock was constructed on the Harlem River Waterfront.[18] This development made the island even more accessible, as now there were vehicular and pedestrian bridges and water access, connecting those from much further away through New York’s complex ferry system.

Today, New York’s Randall’s Island is a popular travel destination, described by the city as, “An oasis in the middle of New York City, Randall’s Island Park comprises most of an island in the East River, between East Harlem, the South Bronx and Astoria, Queens.”[19] The island boasts an impressive and sprawling recreational complex, including Icahn Stadium, a 20-court tennis center, more than 60 playing fields, miles of pedestrian walkways and bike paths, and over 9 acres of restored wetlands.[20] In 2010, the Randall’s Island Community Access Task Force published the Randall’s Island Park Access Guide, an in depth look into the operations and offerings of the park, including maps and historical background.[21] This group works to maintain a visitor-friendly interface, allowing more people than ever to visit one of New York’s greatest treasures. Whether it be concert going, sporting, or just enjoying the fresh air with friends and family, Randall’s Island has an accommodation for every New Yorker and every visitor to experience a true piece of local history.

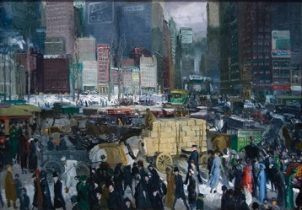

The development of Randalls Island, its changing use over time, its often dark past, and its eventual use for entertainment are all not necessarily unique. While certainly the island has its own story and timeline, many of the trends and struggles faced within were small examples of New York City and American Culture as a whole. Historically, New York City has often been seen as a city of vice, suffering with issues of drinking, prostitution, and rampant poverty and wealth disparity. While the city advanced and modernized, often times the “average” citizen most felt the price of progress, struggling to survive without much help. Painter George Bellows, a New York City painter from the mid-nineteenth century, often depicted these struggles in his works. Pieces such as “Cliff Dwellers”, “New York”, and “Men of the Docks” captured the struggles of New York City’s average citizens, especially those of the lower class. Author Edward Wolner perfectly captures the intended message of Bellows’ work, saying, “Bellows’s New York captures the city’s clashing energies, its centripetal and centrifugal tensions, and its unexampled range of conflicts before such compelling vitality was taken for granted or began to thin out in the globalizing forces that the metropolis itself first concentrated and unleashed.”[22] The city was, indeed, a city of conflicting people and forces, and this can be seen throughout the history of Randalls Island.

What is most interesting, though, is how the most recent history of the Island has truly reflected a greater change in the city of New York. The city has begun to work to change its racial and class struggles, making the city somewhere that anyone can make their own future. The Island, with its development into a space for all residents to enjoy and utilize for exercise, entertainment, and even travel, is an example of how the city is making changes for all of its citizens, not just those who can afford to cash out for them.

[1] History.com Staff, “New Amsterdam Becomes New York,” History.com, last modified September 8, 2010, http://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/new-amsterdam-becomes-new-york.

[2] Randall’s Island Park Alliance, Historical Timeline, Randall’s Island Park Alliance, last modified 2016, accessed September 20, 2017, https://randallsisland.org/timeline/.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Bess Lovejoy, Islands of the Undesirables: Randall’s Island and Wards Island, Atlas Obscura, last modified June 2, 2015, accessed October 4, 2017, http://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/islands-of-the-undesirables-randall-s-island-and-wards-island.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Randall’s Island Park Alliance, Historical Timeline, Randall’s Island Park Alliance.

[8] Lovejoy, Islands of the Undesirables: Randall’s Island and Wards Island, Atlas Obscura.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Lovejoy, Islands of the Undesirables: Randall’s Island and Wards Island, Atlas Obscura.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Randall’s Island Park Alliance, Historical Timeline, Randall’s Island Park Alliance.

[14] Lovejoy, Islands of the Undesirables: Randall’s Island and Wards Island, Atlas Obscura.

[15] Randall’s Island Park Alliance, Historical Timeline, Randall’s Island Park Alliance.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Ibid.

[18] New York City Department of Parks & Recreation, Randall’s Island Park, NYC Parks, accessed October 1, 2017, https://www.nycgovparks.org/parks/randalls-island.

[19] New York City Department of Parks & Recreation, Randall’s Island Park, NYC Parks, accessed October 1, 2017, https://www.nycgovparks.org/parks/randalls-island.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Randall’s Island Park Access Guide (New York, NY: Randall’s Island Community Access Task Force, 2010), https://www.nycgovparks.org/parks/M104/map/randalls_island_park_access_guide.pdf.

[22] Edward W. Wolner, “George Bellows, Georg Simmel, and Modernizing New York,” in Historical Abstracts, previously published in American Art 29, no. 1 (Spring 2015): 106-21, http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=ip,sso&db=hia&AN=101785223&site=ehost-live&authtype=sso&custid=s8475574.

Bibliography

Bellows, George. New York. 1911. Illustration. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:George_Bellows_-_New_York.jpg.

Hell Gate and Triborough Bridges New York City Queens. Photograph. Wikimedia Commons. October 7, 2004. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Hell_Gate_and_Triborough_Bridges_New_York_City_Queens.jpg.

History.com Staff. “New Amsterdam Becomes New York.” History.com. Last modified September 8, 2010. http://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/new-amsterdam-becomes-new-york.

Islam, Adnan. Cherry Blossom Festival. Photograph. Flickr. May 2, 2015. https://www.flickr.com/photos/adnanbangladesh/17231284498/in/photolist-sfEQy3-U4RQ4d-nKQRdH-bnfy3E-UAiRkW-U6y8eu-Tntsgy-UAiMNA-3o1wRy-TntrRW-nrRiux-Tpc4h7-fKDEE1-U4RPuN-cYpNNf-pHVpsZ-ehudz-qEwuXF-88MBrQ-88MF5u-ntmtXU-UpEJBA-mQkddf-xpRtZ-88MAGf-VwiDXS-odXuBe-nyRhQV-nyRhyG-nMn7Dz-nRgVKC-nrQ9Mp-egXVFu-hW31Na-nRkWHT-nyS9iv-4Sru8X-nRgVeY-nyRhzo-nyRxyJ-nR3SPv-hW25vp-7VJChF-UAiTmu-4H8iYt-6KPBaH-UsroCV-UpEK7y-TntnrJ-o9QTiN.

Lovejoy, Bess. “Islands of the Undesirables: Randall’s Island and Wards Island.” Atlas Obscura. Last modified June 2, 2015. Accessed October 4, 2017. http://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/islands-of-the-undesirables-randall-s-island-and-wards-island.

Secondary: This article was written to expose the darker history of Randall’s/Ward Islands in dealing with psychiatric patients and other “undesireable” members of society. I plan to use this to go with a primary source of psychological study conducted on Randall’s Island to explore a different story than the one normally presented for tourist purposes.

New York City Department of Parks & Recreation. “Randall’s Island Park.” NYC Parks. Accessed October 1, 2017. https://www.nycgovparks.org/parks/randalls-island.

Secondary: This source is NYC’s official page for Randall’s Island and tourism advertisement. Demonstrates the history/highlights of the Island as NYC wants the world to see and how the Island is mainly used.

Poull, Louise Elizabeth, Lillie Peatman, Helen Bennett King, and Ada Salome Bristol. “The Randall’s Island Performance Series; Two, Three, and Four Year Tests.” In Columbia University Press. Previously published in Columbia University Press, March 1931. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uc1.$b239233.

Primary: This source is a psychological study conducted in the late 19th-early 20th century analyzing children in the psychiatric hospital on Randall’s Island. Provides insight into the history of the island’s non-sport related history.

Randall’s Island and Ward’s Island — before the Merge. Photograph. Bowery Boys. Accessed October 2, 2017. http://www.boweryboyshistory.com/2009/11/re-visiting-secrets-of-randalls-and.html.

Primary: This image shows Randall’s and Ward Islands before they were merged by a landfill. This demonstrates the evolution of the islands over time to fit the specific needs of the city. I am attempting to track down a more verifiable version of this source either in database or with photographer information.

Randall’s Island Park Access Guide. New York, NY: Randall’s Island Community Access Task Force, 2010. https://www.nycgovparks.org/parks/M104/map/randalls_island_park_access_guide.pdf.

Primary: This guide explains the layout/usage of Randall’s Island Park as it stood in 2010. It will provide insight into how the island is being used primarily for the park and some residential areas.

Randall’s Island Park Alliance. “Historical Timeline.” Randall’s Island Park Alliance. Last modified 2016. Accessed September 20, 2017. https://randallsisland.org/timeline/.

Secondary: This source will be used to establish a timeline of important events/developments in the history of Randall’s/Ward Island. Will be used as a jumping off point for further topics to research.

Wolner, Edward W. “George Bellows, Georg Simmel, and Modernizing New York.” In Historical Abstracts. Previously published in American Art 29, no. 1 (Spring 2015): 106-21. http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=ip,sso&db=hia&AN=101785223&site=ehost-live&authtype=sso&custid=s8475574.