Central Park is the most visited park in the United States of America. Its visitors can recall the plentiful amount of trees, flowers, grass, paths, architecture, benches, rocks, and overall beauty. Today, it has 42 million visits each year. The park spans 843 acres, with 150 acres of lakes and streams.[1] It was not always this way, but from its humble beginnings, it flourished to what it is today. To understand Central Park’s history, one must learn the reasons for its creation, the process of its making, and the outcomes in its earliest years.

During the early to mid-19th century, New York City was becoming only an island of buildings. The city streets were crowded with buildings and little amounts of green land. Manhattan’s inhabitants flocked to the cemeteries for some relaxation in open grass spaces. Originally, De Witt Clinton’s commissioners planned the city’s parks to be located on the shoreline when the city grid was created in 1811. Unfortunately, the shorelines had been taken up by docks, boardinghouses, tenements, warehouses, and factories. This was all due to immigration, job growth, and overall growth of money and business.[2] New Yorkers, especially the upper class, wanted an escape from all of this.

A piece of evidence that is an example of the people’s motivation for Central Park is an article in New York Daily Times. According to the article written on June 4, 1853, by the writer, A.V.W., many New Yorkers wanted a Central Park, but worried it would take too long to construct. It was only an idea at the time, but the city’s people wanted a vast retreat to nature. The article urged legislation to be passed for the park to become a reality. The three needed benefits of the park were health, recreation, and pleasure driving.[3] Parks were thought to benefit health because although the public was not terribly educated about air pollution, they knew that cities did not have clean air. A place that was more nature-like was thought to be a retreat to clean, healthier air. According to the article, New Yorkers wanted a place for recreation to escape to a taste of rural life. The last main reason was for pleasure driving. The streets and avenues were a place for business purposes and general travel. People still wanted spaces for pleasure driving and walking.[4] At this time, the only thing preventing the construction was people who already lived in the designated Central Park area.

In 1852, the area between 5th and 8th avenue, and 59th and 106th street was considered marginal land, which was attractive to poor New Yorkers who needed a place to live. Primarily, these people were Irish and German immigrants, the majority of the poor population. The southern area “were dotted with piggeries, shanties, and bone-boiling establishments…”[5] North of that was a community of mainly African Americans known as Seneca Village. It had churches, cemeteries, and a school. In 1852, Mayor Fernando Wood declared that the land was an “almost uninhabited part of the island.” Other politicians that also wanted the park, lied about the number of victims who would be affected by the creation of the park in order to pass legislation to build the park.[6]

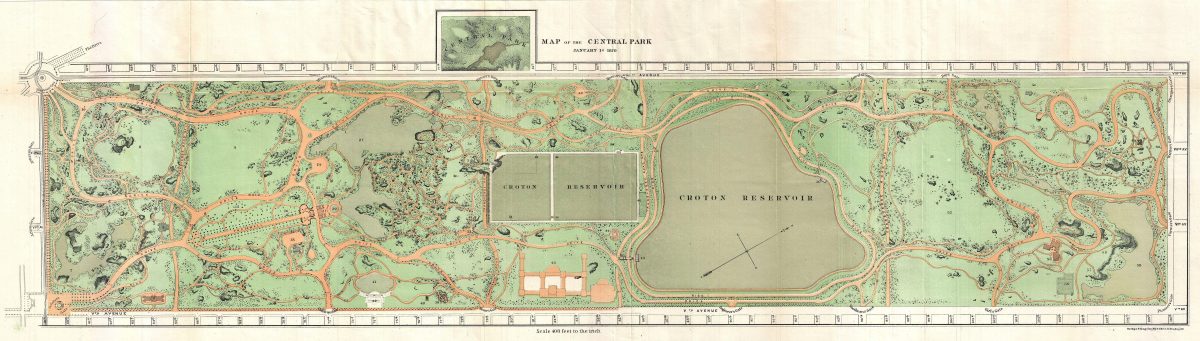

By the fall of 1857, the city had purchased the land from the residents for about $5 million and evicted the sixteen hundred settlers. Not too long after that, the mayor of the city announced a design contest for “The Central Park.”[7] The winners were Calvert Vaux and Frederick Law Olmsted, with their design called “Greensward.” Samuel Parsons, a superintendent of the park, often interacted with the two men and once wrote, “I have often heard Mr. Vaux say that Mr. Olmsted was especially equipped for this study because he was superintendent of Central Park at the time, and therefore necessarily familiar with all of the peculiarities of the terrain. Moreover, Mr. Vaux had a profound respect for Mr. Olmsted’s constructive imagination and artistic power.”[8] Both of their inspirations for what was said to be a “coherent piece of art”, was from the aesthetic of Andrew Jackson Downing, an American landscape gardener.[9]

One aspect of their design that stood out the most was the horizontal roads that helped crosstown traffic flow. This aspect of the park was a requirement for all contest entries, but the Greensward Plan had the road 8 feet below grade, as to not disturb the scenic landscape from its admirers on foot.[10] This was important because the park goers did not want to see urban life. The park was made for an escape to a taste of the rural life, which was eventually accomplished.

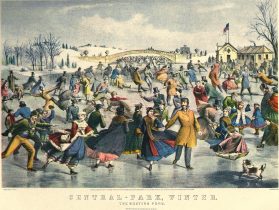

Another early aspect of the park that was particularly impressive was the piping system developed by George E. Waring, Jr., who was the project’s drainage engineer. He, with the help of his team, created clay pipes buried about 4 feet below the ground and 40 feet apart. These pipes contributed water to a large lake that fit perfectly into the park’s design. The lake attracted New Yorkers before the park was even finished. In December of 1858, ice skaters had taken to the frozen lake.[11]

The park was used as much as possible during the creation and construction process. Past news articles are evidence to this. Pieces of writing from the New York Times in 1862 described various events that involved live music being played in the park at the mall. If the weather was nice enough, the schedule was followed with one band after another.[12]

Although Olmsted was known for his eye in design and aesthetics, he did not take well to the critiques and compromises of his work. In June of 1861, the commissioners demoted him to superintend from his chief position because they were “fed up with the heavy expense of Olmsted’s aesthetic extravagance.”[13] They replaced Olmsted with Andrew H. Green, someone who they trusted to pay attention and consider every expense. Only days later, Olmsted enlisted in the Union troops as chief executive officer and fought in the Civil War. During the war, he improved food, water, and clothing conditions while also improving discipline and medical care. By 1865, Vaux had then got their jobs back on the Central Park project. Once they were finished, they won the assignment to design Prospect Park in Brooklyn not many years later.[14]

During Olmsted’s absence, Green did not have much to finish. Most of the park was open to the public for walks, carriage drives, and various activities. About 240,000 trees and shrubs had been planted all over the park. Workers were putting the finishing touches by building a low stone wall around the perimeter of the park. The only thing left to do was to incorporate land between 106th and 110th streets.[15]

Towards the park’s finish, there were a few standout aspects of the park that are still are part of the park today. The Mall is a section of the park that consists of a quadruple row of American elms that surround a quarter mile straight path, the only one in the park. The trees are some of the largest and last remaining stands of American elm trees in North America.[16]

At one side of the Mall is the Bethesda Terrace Arcade. It was considered a main architectural feature to Olmsted and Vaux. One of the highlights of the arcade is the ceiling tile made by England’s Minton Title Company. Although they were made for floors, they were installed in the ceiling. The Bethesda Arcade is the only place in the world where Minton tiles are installed on a ceiling.[17]

After walking through the Bethesda Arcade’s arches, there stands the Bethesda Fountain. This was completed after the civil war. Emma Stebbins created the Angel of the Waters statue on top of the fountain. She was the first woman to be commissioned in New York City for a public art piece. The inspiration for the statue comes from the Gospel of John, in which an angel blesses the Pool of Bethesda and bestowing healing powers upon it.[18] The statue was said to also be made to commemorate the union army’s loss.[19]

One of the largest parts of the park, still in place today, is the reservoir. It was first built as a backup for the Croton Water Works system that was shut down for repairs two weeks each year. The exsisting reservoir is 40 feet deep and holds a billion gallons of water.[20] The first Croton Water Works reservoir is where the Great Lawn is today and was built before Central Park was created. Water from the Croton Aqueduct came from Westchester’s Croton River to the reservoir. Olmsted and Vaux did not think the rectangular shape of this reservoir was appealing, so they used stone walls and plants to hide the site. During the 20th century, the original reservoir was filled and became a lawn space with baseball fields, known as the Great Lawn.[21]

The park has continued to live on for over 150 years. It started as a place for the poor to live and was transformed into an extravagant rural escape from the city life. It took plenty of hard work to but, its creators and designers had a keen eye for details. Central Park’s beauty started in the mid to late 19th century and is still aparent today in its famous structures that are still esist in the park.

[1] “About Central Park” Central Park Conservancy, Accessed November 13, 2016, http://www.centralparknyc.org/about/

[2] RIC BURNS, JAMES ANDERS, AND LISA ADES, New York: An Illustrated History, (New York: Knopf, 1999), 107.

[3] W., A. V. 1853. “A Central Park.” New York Daily Times (1851-1857), Jun 04, 3.

[4] Inbid.

[5] CATHERINE MCNEUR. 2014. Taming Manhattan : Environmental Battles in the Antebellum City. Cambridge, Massachusetts: (Harvard University Press, 2014), 204-205.

[6] Inbid.

[7] RIC BURNS, New York: An Illustrated History. 108.

[8] PARSONS, SAMUEL. “History of the Development of Central Park” Proceedings of the New York State Historical Association 17 (1919): 168.

[9] JEFF L. BROWN, “The Making of Central Park.” 43.

[10] Inbid.

[11] Inbid.

[12] “The Central Park Concerts.” New York Times (1857-1922), Jun 13, 1862.

[13] ALGIS VALINUS. “The Genius of the Place: How Frederick Law Olmsted Transformed American Life.” Commentary no. 3 (2011): 51.

[14] JEFF L. BROWN, “The Making of Central Park.” 43.

[15] ALGIS VALINUS. “The Genius of the Place: How Frederick Law Olmsted Transformed American Life.” 51.

[16] “The Mall and Literary Walk” Central Park Conservancy, Accessed November 13, 2016, http://www.centralparknyc.org/things-to-see-and-do/attractions/mall-literary-walk.html

[17] “Milton Tile Ceiling at Bethesda Terrance” Central Park Conservancy, Accessed November 13, 2016, http://www.centralparknyc.org/things-to-see-and-do/attractions/minton-tiles-at-bethesda.html

[18] “Bethesda Fountain” Central Park Conservancy, Accessed November 13, 2016, http://www.centralparknyc.org/things-to-see-and-do/attractions/bethesda-fountain.html

[19] RIC BURNS, New York: An Illustrated History. 140.

[20] “Reservoir” Central Park Conservancy, Accessed November 13, 2016, http://www.centralparknyc.org/things-to-see-and-do/attractions/reservoir.html

[21] “Great Lawn” Central Park Conservancy, Accessed November 13, 2016, http://www.centralparknyc.org/things-to-see-and-do/attractions/great-lawn.html

Bibliography

BROWN, JEFF L. “The making of Central Park.” Civil Engineering (08857024) 83, (January 2013): 40-43. EBSCOhost (accessed October 5, 2016).

This is a brief history behind central park from a civil engineer’s perspective. It also goes into detail about a few of the famous sections of the park.

BURNS, RIC, ANDERS, JAMES, AND ADES, LISA. New York: An Illustrated History, New York: Knopf, 1999.

This is our “textbook” for the class. I used it for a few facts that paired along with my other sources.

MCNEUR, CATHERINE. 2014. Taming Manhattan : Environmental Battles in the Antebellum City. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2014. eBook Academic Collection (EBSCOhost), EBSCOhost (accessed November 13, 2016).

This secondary source talks about the want for the park and the initial problems with creating it. This source had a few pieces of information other sources do not have.

PARSONS, SAMUEL. “History of the Development of Central Park” Proceedings of the New York State Historical Association 17 (1919): 164-72. http://www.jstor.org/stable/42890080

This is one of my primary sources that is written by one of the superintendents of the creation of central park. He gives insight to the relationship between the two creators of the park.

“The Central Park Concerts.” New York Times (1857-1922), Jun 13, 1862.

This is one of my primary sources that confirms activities in the park, even during its construction. This article specifically reports on music events.

VALINUS, ALGIS. “The Genius of the Place: How Frederick Law Olmsted Transformed American life.” Commentary no. 3 (2011): 51. Literature Resource Center, EBSCOhost (accessed October 5, 2016).

This source goes into detail about Frederick Law Olmsted, who designed the beginnings of central park. It is a secondary source that has a lot of information about him that my other sources do not.

W., A. V. 1853. “A Central Park.” New York Daily Times (1851-1857), Jun 04, 3.

This primary source gave a writer’s insight to the need for a Central Park. Not only were they his opinions, but those of New Yorkers at the time as well.

“About Central Park” Central Park Conservancy, Accessed November 13, 2016, http://www.centralparknyc.org/about/

“Bethesda Fountain” Central Park Conservancy, Accessed November 13, 2016, http://www.centralparknyc.org/things-to-see-and-do/attractions/bethesda-fountain.html

“Great Lawn” Central Park Conservancy, Accessed November 13, 2016, http://www.centralparknyc.org/things-to-see-and-do/attractions/great-lawn.html

“The Mall and Literary Walk” Central Park Conservancy, Accessed November 13, 2016,

http://www.centralparknyc.org/things-to-see-and-do/attractions/mall-literary-walk.html

“Milton Tile Ceiling at Bethesda Terrance” Central Park Conservancy, Accessed November 13, 2016, http://www.centralparknyc.org/things-to-see-and-do/attractions/minton-tiles-at-bethesda.html

“Reservoir” Central Park Conservancy, Accessed November 13, 2016, http://www.centralparknyc.org/things-to-see-and-do/attractions/reservoir.html