The Evolution of Bryant Park

Bryant Park is known as a focal point in New York City. It’s a mini oasis outside of Times Square. In the midst of New York City’s traffic and skyscrapers, you can find this little park filled with fun things to do. Bryant Park is a privately funded park with the goal of creating a rich outdoor experience for visitors. Although we know it as Bryant Park today, this park went through many changes and has a rich history within it. In this paper, we will examine the evolution of Bryant Park.

The early history of Bryant Park started around the late 1600s. It was considered a designated public property by the colonial governor of New York at the time, Thomas Dongan.[1] After events such as Washington’s troops racing across the land in the Revolutionary War, the land was reclaimed under New York’s jurisdiction in 1822. A year later, the land was named as Potter’s Field. Potter’s field, which was originally a public cemetery, was eventually decommissioned in 1840 to prepare for future projects known as the Croton Reservoir.[2] The Croton Reservoir was on the part of land that is now considered the New York Public Library.

The Croton Distributing Reservoir was completed by 1842.[3] This manmade, 4 acre lake was a water supply system known for being a huge engineering progression. The reservoir was surrounded by fifty foot granite walls. It used iron pipes to transport water to the receiving reservoir which was in Central Park. The supply from upstate NY, provided people with fresh water. During the reservoir construction, workers found over 100,000 skeletons buried on top of each other.[4] The skeletons were most likely victims of epidemics and as the construction went on, they were tossed in harbors surrounding Manhattan. Long after that, Reservoir Square, which was the area surrounding the Croton Reservoir, became the fashionable place to be. On top of the walls was a circular promenade with several stone stairways that gave people access to the top.[5] Wealthier families even went there for Sunday strolls. After the expensive aqueduct system opened, the construction of a public park was ordered by the NYC common council in 1846. In 1870, Reservoir Park was created and a just a year later, it underwent a $72,000 dollar renovation.[6] Unfortunately, the park was torn down in the 1900s.

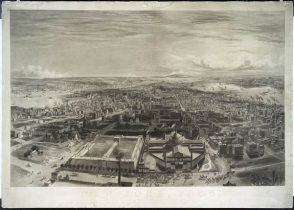

The New York City Crystal Palace was inspired by the Great Exhibition of 1851, which was held in the Crystal Palace in Hyde Park, London. The Great Exhibition was an international museum or exhibition of manufactured goods. After seeing London’s success, New York began preparations by building the palace on the old Reservoir Park. This glass and metal structure in the shape of a Greek cross, was designed by Georg Cartensen and Charles Gildemeister.[7] Next to the Crystal Palace was a Latting Observatory that was 315ft, which was the tallest structure in the city at that time.[8] This iron and wood tower provided patrons and tourists with an unobstructed view of destinations such as New Jersey and Staten Island. The Exhibition of the Industry of all Nations, which was a series of exhibits, became a premiere social gathering place in New York. However, it burned down in a fire in 1856. On October 5, 1858, the Crystal Palace burnt down.[9] Although both structures burned down, the Crystal Palace Exhibition was one of the first major tourism sites. After the Exhibition closed in November of 1854 because of the sponsors losing a lot of money, the property was leased for a few years after.

During the Civil War, the reservoir square’s purpose was used as an encampment for Union Army troops. The Union government issued its first ever draft notices in March of 1863. As a result, of the notices riots broke out. The unused land at the time continued to be the site of encampment up until 1884. After the encampment, there were numerous suggested uses for reservoir square, but many petitions were rejected.

In 1884, Reservoir Park was renamed to what it is called today, Bryant Park. It was named after the editor of the New York Evening Post and civic reformer, William Cullen Bryant. William Cullen Bryant was a big supporter of parks in New York. He thought that having parks were important and even dedicated some of his writing to the importance of parks. He even used his editor position to lead park movements. He put pressure on the government and was an advocate for the most popular of all parks, Central Park.[10] During 1884, plans for the New York Public Library were approved. The designs were submitted by architects, John Merven Carrere and Thomas Hastings.[11] The New York Public Library and Bryant Park share a piece of land so this was a major change to the area. In 1911, the Beaux- Arts building was completed.

A part of Bryant Park was closed to all the public during the 1920s. The park was closed due to the construction of the Interborough Rapid Transit.[12] This subway tunnel ran along 42nd street. The Interborough Rapid Transit acted as a physical movement. This “movement” integrated the ethnic and working class by becoming an essential link of transportation to things such as education, housing, and commercial opportunity.[13] When the construction began in 1922, the IRT workers used Bryant Park as a place to store their tools and materials. They even dug into Bryant Park to contribute to the construction of the subway.

In April of 1932, the Washington Bicentennial Commission initiated a replica of Federal Hall.[14] Federal Hall is known as the first capital building of the United States of America and the site of President George Washington’s inauguration. This replica served as a tribute to Federal Hall and was inspired by the celebration of the 225th anniversary of Washington’s inauguration. This replica was built behind the New York Public Library on the east side of the park. There was a celebration when the hall was completed. The public response to the replica wasn’t as successful as they had hoped, even after adding things such as operas.[15] The Federal Hall replica remained standing until April of 1933 when it was torn down due to not having that much visitor success.

After the Federal Hall replica was torn down, people quickly wanted to find a purpose for the park. The Architects Emergency committee created a contest to redesign the Bryant Park.[16] The Architects Emergency committee was part of the headquarters of the Architectural League of New York. Lusby Simpson was the architect who won the redesign contest. In 1954, an article from the New York Times was written on Lusby Simpson’s life and his contributions to Bryant Park.[17] The Queens-based architect’s plan included a large central lawn, formal pathways, an oval plaza with a memorial fountain, and London Plane Trees. Robert Moses became the parks commissioner in 1934. Architect Aymar Embury II and landscape architect Gilmore D. Clarke helped execute the parks plan of action.[18] On September 14, 1934, the park was open for the public.

Over the years, it seemed as if New York gave up on Bryant Park. Even though Bryant Park was announced as a landmark in 1974, obstacles such as a drug-related murder taking place in the park got in the way and delayed funding to restore it to its fullest potential.[19] By the late 1900s, the Rockefeller Brothers created the Bryant Park Restoration Corporation, also known as the BPRC.[20] Daniel A. Biederman and Andrew Heiskell worked together to create a plan to get rid of the crime and turn Bryant Park into what it was meant to be.[21] By the summer of 1988, BPRC’s plans were approved by the city. Some of these plans included new entrances to make the park more visible, as well as French garden designs. The plan also included adding more lighting to reduce crime even further and renovating bathrooms to make it more visitor friendly. In 1992, the newly redone Bryant Park opened to the public.[22] The success of the park made the whole area around it have higher property value. This resulted in this area being the place everyone wanted to be.

Bryant Park today is one of New York’s favorite destinations. It is a beautiful well-kept oasis in the middle of New York’s hustle and bustle. Bryant Park is maintained by the Bryant Park Corporation, which is a nonprofit corporation.[23] Today, Bryant Park offers a lot to their visitors. This park is not only a historical site, but it is also a monumental site. Although structures such as the Crystal Palace and Federal Hall replica are no longer on the site, monuments that were donated or gifted to the park are there for visitors to see. The BPC honors the traditions that have been a part of the park. They have recreated the historical Reading Room, which allows visitors to read donated books on the property free of charge.[24] Bryant Park offers a lush green lawn that is as large as a football field as well as flower beds surrounding the lawn and are planted seasonally. To compliment the park’s French design, a classic carrousel was added.[25] Bryant Park provides their visitors with games such as chess, ping pong, and putting. Bryant Park has a grill and café, as well as other little stands to eat at. Concerts and tours take place in the park as well. Bryant Park offers seasonal activities such as free art workshops in the summer and the popular Bank of America Winter Village. The Winter Village usually goes from October to early March. This village provides an ice skating rink for visitors, as well as holiday shops and vendors that make it a particularly popular tourist destination during Christmas time. Bryant Park also allows socials and parties to be hosted upon request.

Throughout the years, many people believed Bryant Park had the potential to be something great. This park has a rich history and has gone through a lot to get to where it is today. The people living in NYC at the time reveal a lot about Bryant Park. They were fans of tourism spots. The people of New York were constantly trying to visit the popular place at that certain time period. The many changes Bryant Park went through, reflect the people and their interests at those times. Bryant Park was typically seen as a place for the wealthy to visit but there were times where it was looked down upon. Today, Bryant Park welcomes all types of people and classes. It is a beautiful park we enjoy today that offers us so much. Looking back, Bryant Park is not just a park. It is a historical timeline. Seeing the history it went through just reflects the different time periods that New York went through. From the 1600s to 2016, Bryant Park has been and always will be a staple in park history.

[1] Bryant Park. (n.d.). Retrieved October 04, 2016, from http://www.bryantpark.org/about-us/born.html

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Eliot, M. (2001). Down 42nd Street: Sex, money, culture, and politics at the crossroads of the world. New York: Warner Books. (52)

[5] Ibid.(52)

[6] Bryant Park. (n.d.). Retrieved October 04, 2016, from http://www.bryantpark.org/about-us/born.html

[7] Ibid.

[8] By, J. J. (1934, Aug 26). HISTORIC BRYANT PARK OPENS A NEW CHAPTER. New York Times (1923-Current File) Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.shu.edu/docview/101224163?accountid=13793

[9] Bryant Park. (n.d.). Retrieved October 04, 2016, from http://www.bryantpark.org/about-us/born.html

[10] Lipkowitz, I. (1991, Jul 27). His other park. New York Times (1923-Current File) Retrieve from http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.shu.edu/docview/108702481?accountid=13793

[11] Bryant Park. (n.d.). Retrieved October 04, 2016, from http://www.bryantpark.org/about-us/born.html

[12] Bryant Park. (n.d.). Retrieved October 04, 2016, from http://www.bryantpark.org/about-us/born.html

[13] Eliot, M. (2001). Down 42nd Street: Sex, money, culture, and politics at the crossroads of the world. New York: Warner Books.(17)

[14] Bryant Park. (n.d.). Retrieved October 04, 2016, from http://www.bryantpark.org/about-us/born.html

[15] By, J. J. (1934, Aug 26). HISTORIC BRYANT PARK OPENS A NEW CHAPTER. New York Times (1923-Current File) Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.shu.edu/docview/101224163?accountid=13793

[16] Bryant Park. (n.d.). Retrieved October 04, 2016, from http://www.bryantpark.org/about-us/born.html

[17] Special to The New,York Times. (1954, Jun 01). LUSBY SIMPSON. New York Times (1923-Current File) Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.shu.edu/docview/112932156?accountid=13793

[18] Bryant Park. (n.d.). Retrieved October 04, 2016, from http://www.bryantpark.org/about-us/born.html

[19] Eliot, M. (2001). Down 42nd Street: Sex, money, culture, and politics at the crossroads of the world. New York: Warner Books.(236)

[20] Bryant Park. (n.d.). Retrieved October 04, 2016, from http://www.bryantpark.org/about-us/born.html

[21] Ibid.

[22] Bryant Park. (n.d.). Retrieved October 04, 2016, from http://www.bryantpark.org/about-us/born.html

[23] Ibid.

[24] Ibid.

[25] Ibid.

Annotated Bibliography

Bryant Park. (n.d.). Retrieved October 04, 2016, from http://www.bryantpark.org/about-us/born.html

This secondary source is a website. This Bryant Park website gave me the history on the park and how it become the park it is today. The photo taken from the Latting Observatory is also included in this source.

By, J. J. (1934, Aug 26). HISTORIC BRYANT PARK OPENS A NEW CHAPTER. New York Times (1923-Current File) Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.shu.edu/docview/101224163?accountid=13793

This primary source is about the transformation of Bryant Park.

Eliot, M. (2001). Down 42nd Street: Sex, money, culture, and politics at the crossroads of the world. New York: Warner Books.

This secondary source is a book. It is about the American revolution and the battle against the British. This battle took place on what become Bryant Park over time.

Lipkowitz, I. (1991, Jul 27). His other park. New York Times (1923-Current File) Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.shu.edu/docview/108702481?accountid=13793

This primary source is about the resurrection of Bryant Park. William Bryant plead for a large park and then was honored by Bryant Park being named after him.

“New-York-Bryant Park.jpg. “Wikimedia Commons. Accessed December 13, 2016. Retrieved from http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Bryant_Park

This source includes the image of Bryant Park today.

Special to The New,York Times. (1954, Jun 01). LUSBY SIMPSON. New York Times (1923-Current File) Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.shu.edu/docview/112932156?accountid=13793

This primary source is about Lusby Simpson, the architect winner for redesigning Bryant park.