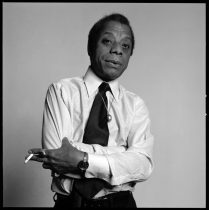

James Arthur Baldwin, born August 2, 1924, is well-renowned, and considered one of the most prolific writers to come out of Harlem, and arguably one of the greatest writers of modern time. Baldwin grew up with his mother, Emma Berdis Jones, who had left his father over his struggles with drugs and alcohol, and would take the name of his step-father, David Baldwin. Being one of nine children, Baldwin received harshest treatment from David, being the only one of the children not biologically his. The treatment from his step-father, on top of a passion and growing interest in literature and his family’s economic status, prompted Baldwin to spend much of his time in libraries, where that passion would flourish even more. From an early age, his teachers saw how gifted he was, reading works like “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” and “A Tale of Two Cities,” reading just about everything he could, with the exception of the Bible, “probably because it was the only book I was encouraged to read.”. By age thirteen, Baldwin had written his first article, titled “Harlem – Then and Now.” Race became a significant emphasis in his literature, since it would be something he would have to come to terms with from a very early age. As the oldest of nine children, he was often left responsible for his younger siblings while his parents worked. And at the nimble age of ten, and later in his teen years, was abused by NYPD officers, which he would write about in Notes of a Native Son (1955).

Baldwin’s literary career took off shortly after the death of his stepfather, when he decided to begin his travels between the New York area and France, where he did much of his writing. Prior to this, he had worked for a defense plant in New Jersey and a meatpacking plant in New York, both places where he notably experienced intense discrimination from those who he worked with. All of this, in conjunction with an insatiable need to explore the world, prompted his first move to Greenwich Village to become an apprentice to Richard Wright, and later work with Harper & Brothers. By twenty-two, he had been published by The Nation for his review of Frederick Douglass’ biography. However, after his experience with racism, by twenty-four, he had decided to move to France using the money from his literary fellowships. There, he worked odd jobs, once as a clerk for an attorney’s office, while also writing editorials for French and American publications. His writings were largely influenced by his experience as a queer, black man living in both the United States and France, and his leftist politics was the foremost in his literature. Baldwin would go on to write works such as Go Tell it On a Mountain (1953), a semi-autobiography about a father’s discontent with his son, and that son’s constant attempts at gaining his father’s approval, and Giovanni’s Room (1956) which was highly criticized at the time for depicting the homosexual relationship between two men, but well-regarded now as one of his better works. Other works of his include If Beale Street Could Talk (1974), which has now notably been adapted into a movie, and an essay, The Fire Next Time, which has made Baldwin one of the most prolific civil rights leaders/writers. He passed away on December 1, 1987 of stomach cancer.

Fun Fact: James Baldwin had a LOT of celebrity friends: Miles Davis, Nina Simone, Ray Charles, and Marlon Brando, are among some of them.

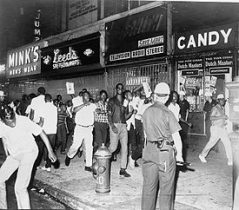

Analysis of “The Fire Next Time”: Baldwin’s The Fire Next Time begins with a meditation of his religiosity as a young, black man growing up in a Harlem, which he deemed, as “more devastated” since the Harlem Renaissance. His religiosity, which later in his life would become nonexistent, in this text, serves to highlight his experience in Harlem, using terms like “safety” to understand religion and what its principles made his life like and his awareness of the people he co-inhabited the neighborhood with. This uneasiness with Christianity and his awareness of the world around him drives the essay, delineating his fears about how he would end up as a person of color; this is to say that he was doomed, in more ways than not so. For instance, he goes onto describe the education process for the boys and girls at his school, in quite bleek terms. “In the same way that the girls were destined to gain as much weight as their mothers, the boys, it was clear, would rise no higher than their fathers. School began to reveal itself, therefore, as a child’s game that one could not win, and boys dropped out of school and went to work. My father wanted me to do the same,” (833). Christianity, in this essay, is spoken of in very  negative terms, as a way of juxtaposing the idea of sin with the fears that one living in Harlem would have. His leftist politics coincide with his racial politics when he recognizes that social mobility for a person of color, such as himself, is not easy. He writes, “One would never defeat one’s circumstances by working and saving pennies…one needed, in order to be free, something more than a bank account” (834). Later, he writes, “…the Negro’s experience of the white world cannot possibly create in him an respect for the standards by which the white world claims to live” (835). This speaks true to the experience of New York as not one that is shared, or one that is meritocratic in any way, but one that preys on people of color and breaks them. After all, it is the reason that Baldwin ultimately moves from Harlem and New York in his early adult life.

negative terms, as a way of juxtaposing the idea of sin with the fears that one living in Harlem would have. His leftist politics coincide with his racial politics when he recognizes that social mobility for a person of color, such as himself, is not easy. He writes, “One would never defeat one’s circumstances by working and saving pennies…one needed, in order to be free, something more than a bank account” (834). Later, he writes, “…the Negro’s experience of the white world cannot possibly create in him an respect for the standards by which the white world claims to live” (835). This speaks true to the experience of New York as not one that is shared, or one that is meritocratic in any way, but one that preys on people of color and breaks them. After all, it is the reason that Baldwin ultimately moves from Harlem and New York in his early adult life.

It is halfway through the excerpt that Baldwin admits this fallacy with viewing the world through a religious lens as a person of color; for Baldwin, the line between becoming a criminal and not were, in reality, nonexistent. “I certaintly could not discover any principled reason for not becoming a criminal, and it is not my poor, God-fearing parents who are to be indicted for the lack but this society” (835). Living in Harlem, and by association New York, has taught Baldwin that this city, and society as a whole, is controlled by the “white man.” The focus of the essay draws back to the idea of fear, fear that his elders, his parents instilled in him, that would seep into his consciousness and ultimately let him realize that he could not “do anything a white boy could do.” The black child’s experience of New York is like an obstacle course, a tribulation that is nearly nonexistent for other such children, nor are they cognizant of this, unfortunately, with power dynamics coming into play. At the end of the day, Baldwin writes, it’s about conquering such fears and not letting it control oneself, as it did for him. He writes, “To defend oneself against a fear is simply to insure that one will be conquered by it; fears must be faced” (838). This fear of acceptance by the church stems from his issues with his father (and/or step-father) and his need for validation, which is why he found turning to the church to be such an easy task, but overall, it is the fear of the person of color to be accepted in New York and American society.

Works Consulted

Baldwin, James. (from) The Fire Next Time. Writing New York: A Literary Anthology, edited by Phillip Lopate, Library of America, 2008. pp. 831-838

“James Baldwin,” Encyclopædia Britannica, February 01 2019, Accessed May 6 2019, https://www.britannica.com/biography/James-Baldwin

“The Enemy Within: The Making and Unmaking of James Baldwin,” The New Yorker, accessed May 3 2019, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/1998/02/16/the-enemy-within-hilton-als