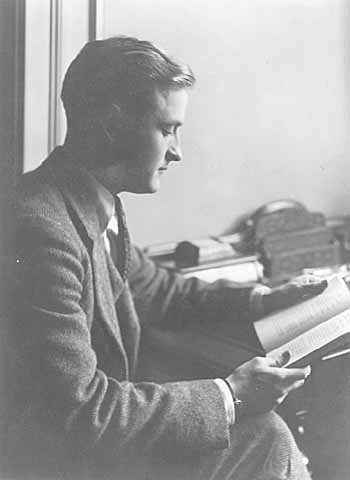

F. Scott Fitzgerald was born in St. Paul on September 24, 1896. He was named after his distant cousin, Francis Scott Key, who famously penned The Star-Spangled Banner. Following this, his family moved, living in both Buffalo and Syracuse New York until returning to St. Paul in 1908. Fitzgerald is best known for short stories that include “Winter Dreams,” “Babylon Revisited,” and “Absolution,” and his larger works, including Tender is the Night, This Side of Paradise, and perhaps most famous of all, The Great Gatsby.

F. Scott Fitzgerald was born in St. Paul on September 24, 1896. He was named after his distant cousin, Francis Scott Key, who famously penned The Star-Spangled Banner. Following this, his family moved, living in both Buffalo and Syracuse New York until returning to St. Paul in 1908. Fitzgerald is best known for short stories that include “Winter Dreams,” “Babylon Revisited,” and “Absolution,” and his larger works, including Tender is the Night, This Side of Paradise, and perhaps most famous of all, The Great Gatsby.

Fitzgerald began producing work at a very young age, publishing his first short story in a school newspaper before entering high school, and producing his first play, The Girl From Lazy J, his freshman year. An eager learner, Fitzgerald attended Princeton University, although he did so sporadically, after returning to St. Paul for a stint due to poor health and grades.

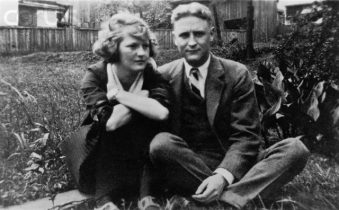

In 1917, he dropped out of school to join the army, where he trained in Kansas at Fort Leavenworth, and began to write his first novel. In the army, Fitzgerald saw himself moving around often, from Fort Leavenworth he went to Camp Taylor, Gordon, and Sheridan, meeting his future wife Zelda before moving yet again to a Camp Mills on Long Island. In 1919, Fitzgerald was discharged from the army, and became engaged to Zelda, working in advertising in New York City, but the engagement was called off, and he moved back to his parent’s home in St. Paul. The shift benefited the writer however, as his first novel was completed and accepted by a publisher, and would go on to be published the following year.

Fitzgerald reconciled with Zelda, and the two wed in New York in 1920. From there, the two continued a pattern of moving from place to place, going abroad to Europe for a spell, and having their daughter Frances. More and more pieces of Fitzgerald were being published and produced, and Tales of the Jazz Age is published in 1922. In 1925, The Great Gatsby is published, and the family moved from Italy back to France, where they had spent a considerable amount of time.

As the years went by and the family traveled, Zelda’s mental health dwindled, and by 1930, she was hospitalized. In 1932, she was institutionalized, and she would be released and re-institutionalized until her death in 1948. During this time, Fitzgerald drunken habits were costing him opportunities, getting fired from MGM after working freelance in multiple Hollywood studios. He died of a heart attack in Hollywood on December 21st, 1940.

Although on spending a short period of time living in New York City, its influence on Fitzgerald’s writing is undeniable. It appears as the setting of many of his works, including the short piece “My Lost City,” The Beautiful and the Damned, and The Great Gatsby.

An Analysis on New York Night Life in “My Lost City” and Djuna Barnes’ “Come Into the Roof Garden, Maude!”

Both Djuna Barnes and F. Scott Fitzgerald wrote of life in New York City, in essays, and looked at how both upper-class men and women can experience the good life there. Barnes’ perspective reflects how upper-class women existed in the culture, and Fitzgerald examines his personal journey in and out of the city, as an Ivy-League Educated man. Barnes’s New York, depicted in “Come into the Roof Garden, Maude!” offers up many sights of the lavish ways people lived at the time, attending garden parties and to the point where even luxuries did not amuse outright—yet underneath the great façade she writes of great cracks in the marble. These “cracks” are what Fitzgerald comes to note in his essay, “My Lost City.”

For Fitzgerald, New York was something to be conquered. He’d ride in triumphantly on his boat, take in the smells and sights, and gather his pay as he did so. He “wanted a man’s world,” and in many ways he got it, moving into a shabby Bronx apartment, playing the part of the New Yorker without truly being inside of it (570). The writer’s dreams did not come true instantly, but in their nature they come across as very male-minded, in the idea that he could see what he wanted in life and simply take it.

Barnes, on the other hand, manages to show the duality of the city life immediately. She plays up the falsities of the rich life, writing “the thing that is really lacking is a sense of humor” (410). There is no mistake to be made, the appeal of the extravagant life is shallow, and truly living in the city and existing in it assumedly takes more than a few rooftop parties. She makes note of the feelings of insider and outsider, writing “even people no further away from home than the Bronx hide [their look] very badly” (411). Those who wish to make it in the city are mistaken, like a bright-eyed Fitzgerald was, that the easy life is attained easily, and that life there is hollow.

From there, we see how Barnes’s New York, however the same as Fitzgerald envisions it, relies on women in particularly to embody an air of forged feelings. Barnes’s women are called “dangerous,” and they act as “the small woman may not,” having everyone believe they are graceful and mysterious beings (413). In reality, as it often ends up with the high-class socialites, everything is not what it seems, and the women know more than they let on. They are the “hungriest thing in the whole of creation,” yet they starve themselves and eat lightly and daintily in front of dates, they ask “where is the roof?” when they know they are on it, and they play up the role society has written them into because it works (414).

Fitzgerald may have found and lost success and his precious vision of New York, but he never recalls sacrificing himself to experience it. What he once wanted, he realized had flaws, “these things were empty for me,” he writes of big homes and nice clubs, yet his desire to make it in the city and feel like he was in the inside crowd persisted (572). Fitzgerald has it all, he meets the “girls” he admired in theaters as a boy, he gains success with his writings, and he can have a drink whenever he desires it. Yet he realizes the big glitzy world he has built for himself isn’t truly the city at all, like the world of actors he was “in New York and not of it” (574). In many ways his big dreams could always been found and accomplished elsewhere, and the appeal of the city cheapens when Fitzgerald sets aside his boyhood dreams of triumph and girls, realizing that what he had he will never get back, and “[he] would never be so happy again” (574).

Fitzgerald’s New York is affected by the changing world, the market would soon crash after he had left it, and the bubbling Jazz Age would never return. As his essay is a reflection, and Barnes’s piece a fictional story, he has the liberty to look beyond, and see past one point in time. However, because Barnes’s story is contained within one rooftop, and one idea, in a sense, it shows that some things may never change. The women who do things solely to appease men, finding dance partners with ease, drinking champagne if they feel like it, may be eternal, but their lives are shrouded in a flippant cynicism in Barnes’s view. “Oh well,” she writes, regarding how nice their lives are, “it’s an awfully jolly thing to be able to dance and watch others dance,” but if one dances forever, she seems to imply, they’ll never leave that rooftop garden (416). Fitzgerald is able to take action in his own life, possibly because he is a man, and independent of the social structures that keep women down and escape the life he thought he wanted. For those atop Barnes’s roofs, her characters resemble those who cannot leave the purposeless life and discover greater meaning past partying, and perhaps do not want to.

Consulted Works:

Fitzgerald, F. Scott, and Djuna Barnes. Writing New York: A Literary Anthology. Edited by Phillip Lopate, Library of America, 2008.

Gale, Robert L. An F. Scott Fitzgerald Encyclopedia. Greenwood Publishing Group, 1998. EBSCOhost, search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=ip,sso&db=e000xna&AN=69323&site=ehost-live.

Mangum, Bryant. F. Scott Fitzgerald in Context. Cambridge University Press, 2013. EBSCOhost, search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=ip,sso&db=e000xna&AN=508361&site=ehost-live.