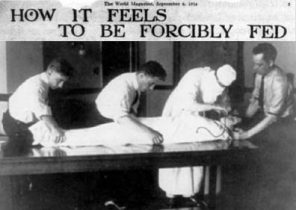

Djuna Barnes was born in Cornwall-upon-Hudson in New York, on June 2, 1892. She was born to an unconventional family, comprised of her parents, her father’s mistresses (he was a practicing polygamist), some siblings, and her grandmother. In her youth, she attended the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, followed by the Artist’s Student League. Barnes developed an interest in journalism, short fiction and illustration; she eventually became a contributor for publications such as the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Vanity Fair, and the New York World Magazine, to name a few. She developed a journalistic style similar to that of the New Journalists of the 1960s, because she recognized the ways in which an observer’s presence shapes the story; as a result, she often chose to either fabricate her subjects, or make herself the subject of her stories. She became a proponent of what might be termed “stunt” journalism—in 1914 she published a story in the New York World Magazine titled “How it Feels Like to be Forcibly Fed”, in which she draws attention the inhumane treatment women’s suffrage activists were subject to. Often, during demonstrations in the fight for women’s suffrage, activists engaged in hunger strikes to demonstrate their commitment to their causes, and to add a bit of urgency to their cause. Typically, demonstrators were arrested and forced to break their hunger strike, which undermined the activists’ agency, and highlighted their plight in light of the obstacles they faced.

in which she draws attention the inhumane treatment women’s suffrage activists were subject to. Often, during demonstrations in the fight for women’s suffrage, activists engaged in hunger strikes to demonstrate their commitment to their causes, and to add a bit of urgency to their cause. Typically, demonstrators were arrested and forced to break their hunger strike, which undermined the activists’ agency, and highlighted their plight in light of the obstacles they faced.

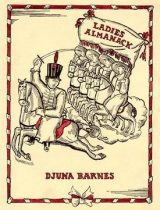

In 1915, Djuna Barnes published The Book of Repulsive Women, a kind of anthology that contained poetry and illustrations that explored different aspects of femininity. Between 1919 and 1920, the Provincetown Playhouse staged three of her one-act plays. In 1920, she moved to Paris, where she joined the Bohemian literary scene. She self-published the Ladies Almanack, in which she satirizes the women of Natalie Barney’s literary salon, and the romantic entanglements that developed amongst them. This particular piece tends to stand out in Barnes’ ouvre not only because of its straightforward approach to lesbian relationships and lesbian social networks, but also  because of its style, which resembles 18th century comic prose. Barnes left Paris for England in the early 1930s; it was where she wrote her most well-known novel, Nightwood. It explores issues of religion, morality and femininity, and lesbianism. Upon her return to New York, Barnes became largely reclusive. She published the 1958 play The Antiphon, which continued Barnes’ exploration of familial dynamics and marginal identities. She died in Greenwich Village six days after her 90th birthday, on June 8, 1982.

because of its style, which resembles 18th century comic prose. Barnes left Paris for England in the early 1930s; it was where she wrote her most well-known novel, Nightwood. It explores issues of religion, morality and femininity, and lesbianism. Upon her return to New York, Barnes became largely reclusive. She published the 1958 play The Antiphon, which continued Barnes’ exploration of familial dynamics and marginal identities. She died in Greenwich Village six days after her 90th birthday, on June 8, 1982.

Djuna Barnes’ article “Come Into the Roof Garden, Maud” explores the perspective of a woman as she moves through a gathering at a rooftop garden, where she mainly interacts with other women. The gendered quality of the space, and of its implications for the experience of the city the narrative details lies in the breadth of the scope of experience that the narrative explores. In Barnes’ story, the narrative is confined to a party on a rooftop garden; some of it is down to the universal elements of such a situation, “10 per cent. soft June air and 10 per cent. gold June twilight, and a goodly percent. of high hung lanterns and the music of hidden mechanical birds…A good deal of the grace of God is there, too” (410), but it is simultaneously that of a specific gathering. The narrator distills everything, from the décor, to the guests, to the conversations at that particular party into generalizations about what one might find at any number of different parties, “someone says something about the types of women that find their way into the atmosphere. Each hour has its particular type—those who come in the beginning and care so much, those who come behind and care less, and those who come in almost too late to have made it seem worthwhile” (413). In this sense, the social lives of women and even women themselves become non-specific and depersonalized; there are categories of women who play certain roles in these kinds of social gatherings. They are props that shape the atmosphere, or accessories accompanying the men, always playing a prescribed role.

Tellingly, the only character that demonstrates any kind of agency is herself a vague suggestion of a character: “She is essentially a crepe; she moves in long, pathetic lines; she is boldly conscious of large hands and ample feet…She is called the ‘dangerous woman’. She likes the name, and she has made the most of it” (413). She plays the part of an alluring, ‘dangerous’ woman, but there is so little substance to her that her escort is about as apathetic towards her as she seems to be towards the whole situation. She is misunderstood by her escort when she expresses her disappointment that the roof garden itself has a roof, and she accepts her disappointment in him, and seems relatively unfazed by it in a way that suggests that women’s experience is not the principal attraction, and their feelings are not worth consideration, when she is given a vague role to fulfill.

“Come Into the Roof Garden, Maude”: http://storyoftheweek.loa.org/2012/06/come-into-roof-garden-maud.html

Works Cited/Works Consulted

Barnes, Djuna. “Come Into the Roof Garden, Maud.” Writing New York: A Literary Anthology, edited by Phillip Lopate, Library of America, 2008.

Barnes, Djuna (1892 – 1982) | Who’s Who in Gay and Lesbian History, Routledge – Credo Reference. https://search.credoreference.com/content/entry/routgayandles/barnes_djuna_1892_1982/0. Accessed 1 May 2019.

Barnes, Djuna [Chappell] | Continuum Encyclopedia of American Literature – Credo Reference. https://search.credoreference.com/content/entry/amlit/barnes_djuna_chappell/0. Accessed 1 May 2019.

“Embracing The Quirkiness Of Djuna Barnes.” NPR.Org, https://www.npr.org/2012/06/16/154846844/embracing-the-quirkiness-of-djuna-barnes. Accessed 2 May 2019.