The latter part of the eighteenth century proved to be a tumultuous time full of upheaval for the colonies, later the United States of America. Even before the signing of the Declaration of Independence in July of 1776, Americans balanced a liminal national identity; they were simultaneously British and decidedly not British. While they were technically British citizens, by the late eighteenth century many colonists felt that they did not enjoy the same rights to representation as their peers in England did. While Britain and America shared a language, American vernacular differed considerably from the Queen’s English. While England boasted a long and illustrious history, the colonies were only just beginning to grow and to pen their own history. As the eighteenth century went on, the rift between Britain and its colonies only continued to grow until the simmering unrest and resentment of the latter resulted in a veritable explosion in the form of the American Revolution.

While the Declaration of Independence promised American men freedom and a more direct say in government, the colonies’ divorce from the mother country proved to be a traumatic one for Americans. Now American men (and women) were forced to reconsider and renegotiate their gender identities as well as their national identities. No longer were they subjects of King George III and his Parliament. Nearly overnight, life as they knew it had changed into something else entirely. With the status quo shattered, American men now were forced to choose between King George and George Washington. This choice was far from an easy one; those who chose to remain loyal to Britain were considered traitors and often were publicly attacked and humiliated by supporters of the Revolution. On the other hand, those who chose to support the revolutionary cause put their own safety and the safety of their property and families in jeopardy. At the same time, citizens of the newborn country were also undergoing significant social changes, especially in terms of gender. The domestic, political, and economic spheres were all shifting at a rapid pace, and many Americans struggled to keep up with the sudden changes. For both Royall Tyler and J. Hector St. John de Crèvecoeur , the threat of American men degenerating into effeminacy and of women overstepping their gender boundaries excessively are ever-present anxieties that their characters experience in their respective works.

The Contrast

Royall Tyler’s The Contrast provides biting satire on eighteenth-century American society’s Anglophilic tendencies and the mostly negative effects of this mentality. One of the most notable (and laughable) effects of many characters’ superficiality and attempts to be what they believe is European and fashionable is the blurring of lines between genders. Many of the women, including Charlotte and Letitia, are hyperfeminine or stereotypically feminine. They are almost solely concerned with fashion, physical appearance, gossip, novels, manners, theater, chatting, flirting, simpering, tittering, curtseying, and other fripperies. They have no concern for more pragmatic, worldly things, such as politics, gravity, and sincerity. Although Maria is not quite lumped into the same category of female as Charlotte and Leticia, she too is subject to succumbing to sentimental lamentations after reading novels. However, unlike her more petty foils, Maria ultimately reveals herself to be more levelheaded, practical, and therefore American. As for the male characters in the play, many of them are portrayed as “dandies” who are almost as feminine as the female characters, with only few exceptions, including Mr. Van Rough and Manly. Charlotte describes the men of her social circle in New York City as “dressy and delicate” as the women are “delicate and dressy,” likening them to each other in a way that makes the two nearly indistinguishable (Tyler ii.i.). The blurring of genders, rather, is what Tyler presents as shameful, as well as a denial of one’s national identity in favor of another.

Colonel Henry Manly

Brother to Charlotte Manly, foil to Billy Dimple, and eventual lover to Maria Van Rough. The ideal American man: a patriot and a “true son of the Republic” [1]. A prime example of the “inelegant goodness” of the true American [2]. No traditional British “comedy of manners could have such a character [as Manly] for a hero”; yet Tyler, in his attempt to establish the new distinctly American hero and truly American literature, chooses to cast Manly as his sentimental hero [3]. He is straightforward, authentic, honest, and does not bother with a false performance.

Billy Dimple

Foil to Colonel Henry Manly, “lover” to Charlotte and Letitia, son to Van Rough’s late business partner and friend, Van Dumpling, and fiance to Maria. A “dissembling effete,” Dimple is ashamed of his country and [does] his best to ape the bon ton of Europe”; he spends much of the play in England [4]. He is one of the “dressy and delicate” dandies that Charlotte likens to the “delicate and dressy” coquettes of New York City [5]. He is a greedy, effeminate Anglophile, and stands in stark contrast to the authentic, masculine Colonel Manly.

Van Rough

Father to Maria Van Rough and friend and business partner of Dimple’s late father, Van Dumpling. He is masculine, but represents the Old World America of the Dutch settlers. He is old-fashioned in his opinions and mannerisms, and more “rough around the edges” than the likes of Colonel Manly.

Charlotte Manly

Sister to Colonel Manly, friend to Letitia, lover to Dimple. A hyperfeminine or stereotypically feminine “libertine,” she is almost solely concerned with fashion, physical appearance, gossip, novels, manners, theater, chatting, flirting, simpering, tittering, curtsying, and other fripperies [6]. Tyler portrays her as a ridiculous remnant of colonialism; by the end of the play, she begins to realize the error of her ways.

Letitia

Friend to Charlotte Manly, lover to Dimple. Like Charlotte, she is a vain, petty, coquettish “libertine” with little concern for anything outside of her appearance, flirting, and gossip [7].

Maria Van Rough

Daughter to Van Rough, fiancee to Dimple, lover to Colonel Manly. The “modest and grave” Maria stands in stark contrast to the likes of Charlotte and Letitia [8]. She serves as the play’s “sentimental heroine,” pragmatic (despite her penchant for romantic, sentimental novels), authentic, and down-to-earth, she is the ideal match for the equally levelheaded, realistic, all-American Colonel Manly.

Letters from an American Farmer

Farmer James

A humble American farmer settled in Pennsylvania, James establishes numerous correspondences with an educated Englishman, much to his excitement and initial disbelief. In his letters, James extols the virtues of the solitary, hardworking, simple, practical, humble American and his lifestyle. While revolutionaries rejoiced in their newfound freedom from oppression, many American men “such as Farmer James, who had wished to forge an ambitious new American identity that valued farm and family, suddenly had to choose sides in the struggle between the rebels and the British, or else watch their homes be destroyed in the crossfire” [9]. The resulting social, political, economic, and agricultural upheaval in the aftermath of the revolution hardly benefited men like James; “not only was the…Revolution destructive to communities, farms, and families, but it also pushed the country toward an individualistic masculinity that was wasteful and short-sighted in its treatment of the land” [10]. This definition of masculinity favored the role of politician, soldier, and revolutionary over that of the lowly farmer.

Although the American man was considered generally masculine in the traditional sense, he was by no means a brute. James describes himself as a “farmer of feelings,’” and has no qualms sharing in his letter the sheer joy of playing the parts of husband and father [11]. Thinking of his wife as she “spins, knits, darns, or suckles [their] child” by the fire or as he “play[s] with [their] infant,” he cannot help but be nearly overwhelmed with contentment and happiness at the stable domesticity of it all [12]. Still, he claims that he “cannot describe” the full extent of his deep emotions, alluding to the “simple” American’s reputation for his lack of articulateness, as well as his uncertain and shifting gender identity [13].

Farmer James’ Wife

Farmer James’ unnamed wife. She appears not to share her husband’s struggle with her own gender and national identities. She is always presented in an “idealized form; she works hard, she maintains a cheerful disposition,” “never fails to perform her uxorial tasks,” “and perhaps most important from James’ perspective, she knows her place” [14]. She hardly ever challenges him, save for the scene in the beginning of Letters in which she finds it difficult to believe that an educated Englishman would wish to interact with James. She exhibits a “steadfast sense of her own gender role,” unlike her husband, who struggles with an internal back-and-forth regarding his identity as a man in a burgeoning country also attempting to make sense of itself [15]. James’ wife is his rock; not unlike the wives of Nantucket, she tends to her maternal and wifely duties, as well as lending a helping hand with other aspects of the farm. Overall, she seems to have adapted better and more quickly to the new America than James.

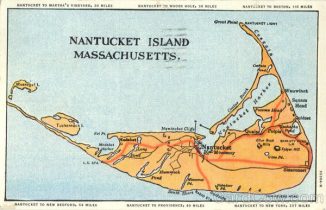

Nantucket Wives

While James’ wife does involve herself in the discussion regarding James’ correspondence with F.B., the women of Nantucket take upon themselves nearly all the responsibilities of their men when the latter travel. James (and perhaps Crevecoeur) is surprised by the nerve and initiative of the Nantucket women; “[t]o this dexterity in managing the husband’s business whilst he is absent, the Nantucket wives unite a great deal of industry” [16]. They handle their husbands’ businesses and finances, and they do so responsibly and intelligently. Farmer James gives the specific example of the “wife of Mr. C–n, a very respectable man, who, well pleased with all her schemes, trusts to her judgement, and relies on her sagacity, with so entire a confidence, as to be altogether passive to the concerns of his family” [17]. Here James passes subtle judgment on Mr. C-n and his alleged passivity.

Rather than take on the traditional role of head of his household, Mr. C-n allows his wife to handle both her traditional duties as wife, mother, and homemaker, as well as his assigned responsibilities as paterfamilias; thus, Mr. C-n does not exhibit the traits of the ideal American man, as he is not described as conventionally hardworking. In the Nantucket letters, James simultaneously (tentatively and perhaps grudgingly) praises women for their productivity and business savviness (only in the absence of their husbands), while also chastising the men for their passivity and for allowing their women too much freedom (particularly with the women’s endemic opium use). By writing and thinking about the unconventional family and gender dynamics of the people of Nantucket, James attempts to come to terms with his own identity as a man in the new America.

Ultimately, Hector St. John de Crevecoeur and Royall Tyler both took it upon themselves to address what they perceived to be a latent and ever-present anxiety in their society concerning identity in all its forms. War inevitably leaves indelible marks on land, families, cultures, and societies, and the American Revolution was no exception. The concept of American nationhood was initially undefined post-revolution, and was slowly molded as the eighteenth century progressed and the American people grew accustomed to their new identities. The war and independence from England lead to dramatic shifts in the family unit and gender roles within the domestic sphere, which left many men, including those like Farmer James and Colonel Manly, stuck in a sort of limbo wherein they did not quite know how to exist comfortably in a new and unfamiliar America. Women, however, took on their more flexible roles outside of the home or in other aspects of the home more readily than their men did. Crevecoeur and Tyler ultimately define the ideal man in the new Republic as rugged, hardworking, familiar with physical labor, and independent, as well as able to avoid the slippery slope into effeminacy that was a constant threat for them due to the lingering influence of Europe. The fact that both of these works are still read hundreds of years after the Revolution and their respective publications raises the question of whether the mystery of the authentic American has yet to be solved.

References

Bishop, James E. “A Feeling Farmer: Masculinity, Nationalism, and Nature in Crevecoeur’s Letters.” Early American Literature, vol. 43, no. 2, 2008, pp. 361-377. EBSCOhost, search.ebscohost.com/login.aspxdirect=true&AuthType=ip,sso&db=mzh&AN=2008301799&site=ehost-live&authtype=sso&custid=s8475574.

Carew-Miller, Anna. “The Language of Domesticity in Crevecoeur’s Letters from an American Farmer.” Early American Literature, vol. 28, no. 3, 1993, pp. 242-254. EBSCOhost, search.ebscohost.com/login.aspxdirect=true&AuthType=ip,sso&db=mzh&AN=1993021420&site=ehost-live&authtype=sso&custid=s8475574.

de Crevecoeur, J. Hector St. John. Letters from an American Farmer. American Library, 1963.

Siebert, Donald T., Jr. “Royall Tyler’s ‘Bold Example’: The Contrast and the English Comedy of Manners.” Early American Literature, vol. 13, no. 1, 1978, pp. 3-11. EBSCOhost, search.ebscohost.com/login.aspxdirect=true&AuthType=cookie,ip,sso&db=mzh&AN=1978108815&site=ehost-live&authtype=sso&custid=s8475574.

Tyler, Royall. The Contrast. 1787, www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/554/pg554.html.