Do Elections Really Matter in the Congo?

by Roger Alfani

Some African politicians claim that they do not organize elections to lose them. This discourse echoes also in the Central and Great Lakes region of Africa’s politics like in Cameroon, Congo, Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Gabon, and Rwanda. They present a number of commonalities such as similar colonial masters (France or Belgium); inherited a dictatorship; etc. The DRC is the most unstable and the one that is embroiled in conflicts especially in its Eastern provinces. In fact, these conflicts have caused the death of more than 6 million Congolese since the mid-1990s. Not only have recent long-delayed elections worsened the sociopolitical situation in the country, but they have led one to ask the following question: Do elections really matter?

While the answer to this question may be in the affirmative, it is not the case for many Congolese who have been deceived in the three electoral processes (2006, 2011, and 2018). For the Catholic Church in the DRC, the three electoral rendez-vous have been a disappointment as the results were neither truthful nor just. For instance, regarding the first election in 2006, the Conference of bishops associated peace to the truth of the polls. That is, the truth of the polls was the guarantee for peace. Five years later in 2011, the Catholic Church — which has provided more than 40,000 observers each election (10,000 more than the previous one) — declared that “results were not conform to truth and justice.”

Contrary to the two previous electoral processes, the Catholic Church has not only worked in collaboration with the Protestant Church (Church of Christ in Congo, ECC), but it has released more details in regard to polling booths’ results. However, it has come short to publicly name the winner of the 2018 election. While the Catholic Church and the ECC have played an important role in last election, this article does not exclusively examine these religious bodies. However, this piece highlights the importance of elections of an emerging democracy as the DRC.

Elections represent a mechanism many societies have embraced to democratically choose their own representatives. Two terms are very important here: choice and democracy. Not only does choice means a variety of possibilities, but it also means non-coercive acts in the determination of one option over an another. The word democracy connotes at least two things. On the one hand, it centers on the rights of citizens to regularly choose their governments, rulers, and policies, usually through a voting process. On the other hand, democracy refers to constant interactions between state and citizens where the delivery of goods and services come into play. In the delimitations of the two terms — choice and democracy — people enjoy the freedom to determine the kind of regime that should rule over them and thereby giving legitimacy to the regime and strengthening the overall democratic system. This understanding may be perceived as a normal process for some states and viewed as a utopic for several others. While the process may be normal for many Western states, like the U.S., Canada, France, and few African states (e.g. Ghana, South Africa), several other states like the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) register for the abnormality of a democratic transition of power.

Providing citizens with the opportunity and right to choose their leaders through fair competition does not necessarily imply a subscription to the liberal ideology. Rather, elections serve as a lever in the hands of citizens to fulfill at least two objectives. On the one hand, it facilitates the establishment of a social contract between leaders and populations in part for accountability purposes. On the other hand, it strengthens democracy and consolidates peace.

While this process may not be perfect overnight, strong democracies have a moral obligation to show solidarity in accompanying new democracies on the same journey that guarantees peace and prosperity for all. Any compromise on this principle (democracy) can only lead to institutional instabilities and illegitimacies of such states. As a result, these states not only threaten international peace and security but also jeopardize the well-being of its own population. In other words, a bargained democracy is no better than non-democracy or dictatorship in part because it pollutes its very nature. The case of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) serves as a test where democracy is on a balance with dictatorship.

Whether in heavy rain or after hours of waiting, on December 30, 2018 more than 18 million Congolese defied all obstacles to exercise their right to determine their next president and member of parliaments.

Indeed, December 30 was a result of three postponements, with a total of 2 years of delay which led to additional blood-shed and deaths. While some Congolese were allowed to vote, others in the Eastern Congo, were denied the same privilege. In fact, the National Independent Electoral Commission (CENI) unilaterally decided to postpone for March 2019 the voting right of Congolese living in three cities (Beni, Butembo, and Yumbi) for both security and health reasons. Opposition parties had a different explanation. For them, denying this right was not only unjustified, illegal, and out of the CENI jurisdiction, but they also argued that they campaigned in those areas without any threat. The only possible explanation, according to them, was that the CENI, infeudated to the incumbent president, sought to deprive them from millions of supporting votes.

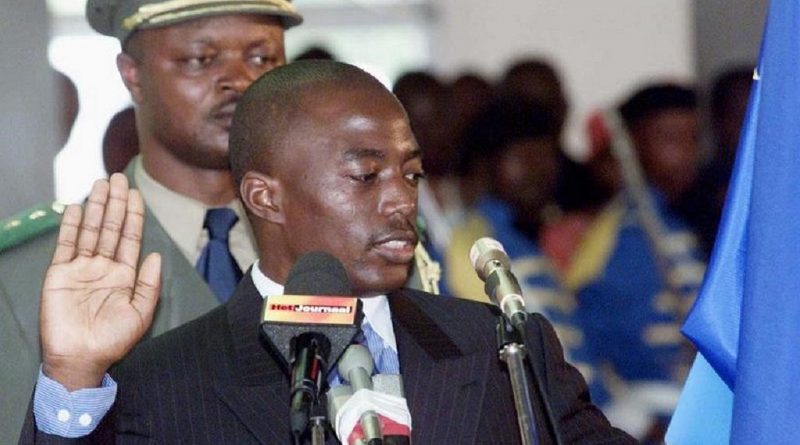

For 17 years in power — almost half of Mobutu’s presidency — the incumbent president, Joseph Kabange Kabila, was no longer allowed to run for a third term as stipulated in Art. 70 of the Congolese current constitution. All ways to prolong his stay in power seems to be at work: delays, conflicts, consultations, institutional levers, etc.

In 2001, Joseph Kabila arrived in power after the killing of his predecessor, Laurent-Desiré Kabila, in a situation that is still a riddle for many observers and a pending case in justice. Many suspects related to Laurent-Desiré Kabila’s assassination are still languishing in jails waiting for their judgement. The 2002 Accord-Global et Inclusive peace agreement ratified between the Congolese government and rebels (MLC, RCD, etc.) — both backed by regional armies from Zimbabwe, Angola, Namibia, Rwanda, Burundi, and Uganda — ushered in a three-year transition period during which the country’s apparatus was controlled by one president and four different vice-presidents: System “1+4.”

In 2006, the country was able to organize its first presidential election with the assistance of the international community, particularly from the United Nations Mission in the Congo (MONUC). It is worth noting that UN peacekeepers are in their second mission in the Congo. The first UN intervention in the Congo (United Nations Operations in the Congo, ONUC), authorized by the Security Council (Resolution 143), occurred just after national and provincial elections, and independence of the Congo in 1960. During this same period a Katanga secession led by Moïse Tshombe and supported by Belgians was happening. This intervention not only involved the deployment of more than 18,000 peacekeepers with an annual cost of $120 million at the time, but was also during this mission that Dag Hammarskjöld, Swedish UN Secretary-General, died in a “suspicious” plane crash in the Congo.

It is only this year, 2019, fifty-eight years later, that the mystery over the cause of this crash was unveiled: a Belgian mercenary, Van Risseghem, acknowledged to have shot down the plane of Secretary-General Hammarskjöld. While by the end of this first mission, in June 1964, the country’s secession was avoided, ONUC’s (willing?) failure to protect Congolese Prime Minister Patrice Emery Lumumba — who was accused of leaning toward and promoting communism and killed in January 1961 — continue to negatively taint this mission, including Western powers.

Even though the Congo’s sovereignty was restored with the assistance of UN forces, the Congolese state has remained relatively fragile, especially after the fall of Mobutu’s regime in the late 1990s. (It should be noted that President Joseph-Desiré Mobutu was not only supported to take power in 1965, but maintained control with the aid of Western powers, particularly the U.S., until the early 1990s). Coming back to UN missions in the Congo, the second intervention of UN forces happened in the late 1990s and early 2000s.

Security Council Resolution 1279 authorized the deployment of 500 observers in the Congo constituting the MONUC mission which reached more than 20,000 peacekeepers by 2010. In the same year, it was changed into a stabilization mission (United Nations Organization Stabilization Mission in the DRC, MONUSCO). Many have critiqued and questioned the ambiguous role/mandate of peacekeepers including in their three missions in the DRC. The friendly kind of relationship, even amidst breaches of human rights, between the Congolese State and the UN missions in the Congo feed this ambiguity. Two examples can illustrate it.

First, in 2012, M23 rebels captured the city of Goma under their watch. After an international uproar, UN peacekeepers were able to recover the city. Second, the confusion surrounding the (in)explanation or Congolese cover-up of the death of two UN experts — American Michael Sharp and Swedish Zaida Catalan — in the Kasai province (DRC). Many observers have complained the accommodation the incumbent president and his regime have received for human rights infringements and financial corruption. Even though some democracies have implemented some targeted sanctions and have warned of additional ones, their effectiveness is questionable. Do economic sanctions work for a regime in a survival mode? They have not met their intended effects. Rather, they have produced the opposite result, as seen in the DRC.

*Note: The Congolese elections are an on-going issue with updates occurring daily. The information presented in this piece is meant to give an in-depth analysis of an changing event.

Roger Alfani is an Executive M.S. of International Affairs candidate at the School Diplomacy and International Relations with specializations in Foreign Policy Analysis and International Law and Human Rights. He has his PhD in Religious Studies and Peacebuilding from the University of Montreal. While pursuing his M.A., Dr. Alfani is an Assistant Research Fellow with the Dean of the School of Diplomacy and International Relations at Seton Hall University. His research interests are the role of religious actors in peacebuilding and the nexus between religion and foreign policy. He has published on the role of churches in conflict transformation in Goma, Democratic Republic of the Congo. His current projects include the publication of his book Religious Peacebuilding in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (2019).

No, elections do not matter. The word democracy is completely misunderstood by the 90% of the population of the world. There is no democracy, anywhere. You have defined democracy as – “…that guarantees peace and prosperity for all.” You point out that western world has democracy, but have you verified if your definition is working there? – In USA alone 40 million people are below poverty line, after 200 years of democracy. Same is true for UK also.

So, what is the root cause of failure of democracy? We use secret ballot for selecting our representatives. But our representatives do not have secret ballot in their capitol. If my representative cannot use secret ballot, and he is forced to use public ballot, then my vote becomes public also. This is how democracy has been stolen at the capitol and we do not see the fulfillment of the “social contract” we expected when we used secret ballot to elect them. No secret ballot means no democracy, no matter when and where you vote. Take a look at the central bank chapter and also the moneyless economy (MLE) chapter in the free book at https://theoryofsouls.wordpress.com/