The Power of Passports: Visa Waiver Restrictions in the US

In the name of national security, the United States Congress has inserted US interests into the travel habits of foreign nationals, with little consideration for the impact of their actions.

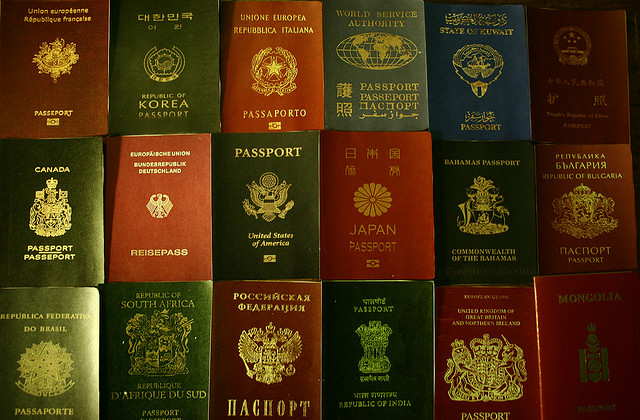

On Thursday, new restrictions to the United States’ visa-waiver agreement with 38 countries effectively removed persons that have visited Iran, Iraq, Sudan, or Syria on March 1, 2011 or after from the program. Anyone fitting that description will now most likely have to go through the full visa application process to visit the U.S., rather than simply use their passport for travel as stipulated in the 1986 agreement. These restrictions would extend to any citizen of the 38 countries that retains dual citizenship of the four nations flagged in the new revisions.

Despite its name, the visa-waiver program does not create the Schengen-like “free pass” zone to and from the US its critics describe when defending more stringent visa policies. It is instead a security agreement between states to have citizens thoroughly screened before leaving their country of origin, delegating the burden of investigation to domestic governments rather than American customs while hopefully preventing those with criminal intent to even reach the site of their intended crime.

The Obama administration has already advocated for specific evaluation of journalists or humanitarian workers, whose professions automatically bring them to the dangerous regions in question. They should go further, developing a separate track of bilateral policies for those whose occupation is by nature international, rather than treat the entire group with suspicion based entirely on geography.

Creating discriminatory exceptions based on travel alone is an extension of the “over there” mindset that for the better part of a decade plagued American strategy in the regions in question. Lawmakers in Congress calling for the strict implementation of these new regulations, without exception or evaluation on a case-by-case basis, betray a narrow worldview that is ultimately out of step with modern demographic fluidity. Beyond the obvious transnational nature of aid work or journalism, conflict zones by their very natures create diasporas, communities of common nationality that only grow and scatter further as the violence in their country of origin increases. Someone that was in Iraq or Syria five years ago – or even five months ago – was most likely fleeing the very radicalization and destruction Americans fear will infiltrate their own domestic shores.

Furthermore, the US is not the only party with interests in the region. Ever-increasing globalization means trade relationships may be established bilaterally, with little regard for ongoing political strain between the US and a given government. While this may be uncomfortable diplomatically, the U.S. attempting to flag business travel in a region where Americans themselves have construction and security contracts borders on the hypocritical.

Beyond that, requiring full visa applications for those retaining dual citizenship from the unstable regions in question, even if they themselves have never visited those places, is a demand for assimilation that betrays Western values of individualism. Restrictions such as these criminalize personal, ethnic and national history, forcing full citizens of the West to reconsider their origins as baggage to be discarded if they wish to enjoy freedom of movement, simply because governments or persons still active there threaten US interests. It is a dramatic overinflation of data’s value to national security.

Travelling from a conflict zones a person may carry anything from infectious diseases to haunted memories. These should be treated accordingly upon arrival, if not before. The government of a single nation, however, cannot quarantine radicalization or anti-American sentiment. Ideas cannot be constrained by borders, and to marginalize the citizens of other nations in the name of “containment” is a drastic overreach of legislative control that cannot provide Americans with the physical – or emotional – security we so desire.

—

Karina Taylor is the Editor-in-Chief of the Journal of Diplomacy. She is a second-year graduate student at Seton Hall’s School of Diplomacy, specializing in International Organizations and Foreign Policy Analysis.

Follow the Journal of Diplomacy on Twitter: @JournalofDiplo