Now That She’s Won the Election, Dilma Faces Difficult Choices

Having narrowly won the Brazilian presidential election on October 26, Dilma Rousseff uttered a remark that is somewhat unusual for a politician in which she said, “I want to be a much better president than I have been until now.” This was her acknowledgment that things had gone wrong in the country, previously. Brazil had spent the better part of the last decade growing rapidly, and has often been touted as an emerging world power, however. More importantly, Rousseff’s comment illustrated the widespread recognition, including by the president herself, that the policies of the ruling Workers’ Party were not working well. Many Brazilians even believed that the policies of the Workers Party contributed to the recent economic downturn as well. Indeed, the international markets did not show the same level of confidence that half of Brazil’s population did in Rousseff, with Brazilian stocks and currency plunging on the Monday following the election. Mrs. Rousseff’s first task after being reelected will be to reassure the markets and prevent the Brazilian economy from slipping any further.However,to do that she will have to make difficult choices; ones which may clash with the populist, left-wing message which she successfully used against her opponent and win the votes of Brazil’s lower classes.

Brazil’s growing economy, the product of a global commodities boom during the 2000s, financed social programs aimed at alleviating poverty as well as creating budget surpluses of the kind which most “developed” countries could only covet. That boom, however, has ended, and the government’s attempts to stimulate the economy through targeted tax cuts and interventionist micromanagement have helped to turn that surplus into a growing deficit while undermining the investment climate. Though unemployment remains low, inflation has risen steadily to 6.75%. Rousseff’s unsuccessful challenger, Aecio Neves, had promised pro-market and pro-business reforms but was attacked by the Workers’ Party for allegedly wanting to undermine popular social programs. Rousseff referred to Neves as the “bankers’ candidate,” as part of a largely successful strategy which led to a distinct economic and geographic cleavage in voting patterns in which Rousseff won the poorer north whilst Neves performed strongly in the wealthier south. Exploiting economic gaps and “class warfare” themes may have been a good election strategy but if Rousseff wants to live up to her election promise of being a better president, she will have to make difficult choices which may alienate her core supporters.

To save Brazil’s public finances from further deterioration, Rousseff will have to reverse her previous strategy of cutting taxes on certain consumer goods, while preserving current spending levels. Serious tax reform, rather than selective tax cuts, will have to be on the agenda. But this must coincide with spending cuts. According to The Economist in an article from last year,

“Every Brazilian administration since the return to democracy in the late 1980s has increased public spending as a percentage of GDP…The tax take is now 36% of GDP, far more than in other middle-income countries, or the rest of Latin America, or indeed several developed countries, including Japan and the United States. At the federal level, the increase has been driven by income redistribution…including the famous Bolsa Família, which gives modest sums to around 12m very poor families; non-contributory pensions for rural workers; unemployment benefits; and a state top-up for workers in the formal sector on very low salaries.”

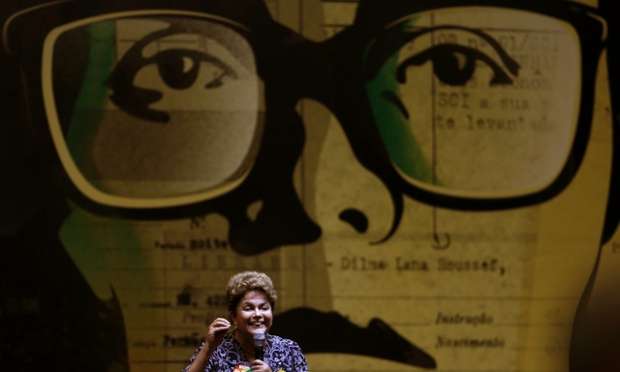

In other words, the social programs aimed at lifting Brazilians out of poverty, which Mrs. Rousseff used as a rallying point, and which even Mr. Neves was careful not to criticize, must not continue to be a “sacred cow” in Brazilian political discourse. Though Bolsa Familia is unlikely to be unwound due to high popularity (and in any case its cost is not onerous), cutting benefits for the poor linked to an ever-rising minimum wage should be on the table, as well as Brazil’s overly generous pensions schemes for both the public and private sectors. Financing must also be found for government programs. These programs promote long-term investment and the building of a skilled workforce, namely in infrastructure and education, which should take priority over redistribution schemes. All this is, of course, is counter-intuitive to Rousseff and the Workers’ Party. It will undoubtedly make enemies for Rousseff out of many in her own party and many of the grateful poor Brazilians who put her back in office. But tough decisions are necessary, and perhaps Rousseff’s background of political radicalism (she is a former Marxist guerrilla, having fought against Brazil’s military dictatorship in her youth) and support amongst the lower classes make her the only person who can actually deliver reform, or at least will have a better chance of doing so in class-conscious Brazil than the patrician Aecio Neves. Regardless, the pressure for change is mounting, and will continue to mount.

Brian Sherry is a graduate of Seton Hall University and an Associate Editor with the Journal of Diplomacy. He is currently pursuing a Master’s degree in International Relations and Strategic Communication at Seton Hall. He specializes in Foreign Policy Analysis.

Featured Image: Source