A new book examines the critical art of rethinking.

Adam Grant writes, “If knowledge is power, knowing what we do not know is wisdom.”

Adam Grant writes, “If knowledge is power, knowing what we do not know is wisdom.”

Reading Think Again was a pleasure, and it is easy to see why Grant is a top-rated professor at the Wharton School. It is chock-full of examples, illustrations and recommendations to improve individual and group thinking. I plan to re-tool my presentations and lectures to incorporate many of Grant’s points.

However, at the same time, as one reads, many counterarguments come to mind. I find myself thinking,

“Yes! But consider this …” Such a reaction, of course, demonstrates Grant’s principles of rethinking through debate and openness to new ideas.

Grant’s themes in support of good leadership are covered in three parts:

- Start with yourself. A leader’s voice carries weight: his/her insight helps performance; his/her expertise increases productivity. Grant points out how important it is to become self-aware of biases that blunt one’s effectiveness — a tone-deaf voice, a mistaken “insight” or a faulty assumption.

- Include the team. Just as an individual can embed faulty assumptions or biases, groups are subject to the same errors. Grant offers tactics for building group dynamics that overcome some of the barriers to rooting out our mistakes.

- Resolve conflict. It is one thing to root out counterproductive tendencies within oneself and within the group, but there are times when people are at odds over the substance of the issues at hand. Grant offers several ways to engage in helpful debate, be more persuasive and open the field for deeper communication and nuance as well as ways to create genuine dialogue and increase the odds of resolving thorny issues.

Knowing How to Think Instead of What to Think

As we move into positions of higher leadership, we accumulate a growing record of performance and success. This trove of personal triumphs, however, may blind or bias us in two ways. First, it may capture us inside the “overconfidence cycle” identified by Grant: (a) pride, (b) conviction, (c) desirability & confirmation biases and (d) validation (See the Overconfidence Cycle graphic below). Second, the elements of the past may calcify in our thinking as the “winning formula,” closing our minds to what may be tomorrow’s better idea (a form of faulty validation).

Nobody likes being wrong. As a leader, being wrong looks weak, undermines credibility, and sows doubt. For serious topics, business decisions and preservation of our self-image, discovering we are wrong is unpleasant at best and devastating at worst.

Grant goes to some length to destigmatize “being wrong.” His goal is to overcome the inner resistance to self-appraisal that blinds us to our mistakes and keeps the teams we lead clinging to unproductive strategies for far too long.

Being wrong is OK. We should embrace the discovery that we are wrong. Grant describes a conversation with Daniel Kahneman, the Nobel Prize-winning psychologist and author of Thinking Fast and Slow (a work that is a more profound treatment of Grant’s topic). Grant had just presented research results that conflicted with Kahneman’s: “His eyes lit up, and a huge grin appeared on his face. ‘That was wonderful,’ he said. ‘I was wrong.” Later over lunch, Kahneman made the point that he genuinely enjoys discovering when he is wrong because “it means he is now less wrong than before.”

Grant also quotes Ray Dalio, founder of the hedge fund Bridgewater: “If you don’t look back at yourself and think, ‘Wow, how stupid I was a year ago,’ then you must not have learned much in the last year.”

Grant’s central theme is to recognize that the road to the truth sometimes travels through the territory of error, doubt, curiosity and, ultimately, discovery. This road begins with looking inward at one’s own views and then, when in a position of leadership, to employ constructive conflict in our teams.

How do we encourage others to open their minds, rethink their positions and establish communities of people committed to open-mindedness? This is Grant’s true purpose in writing the book, and he provides many useful tactics to persuade others, diminish prejudice, motivate others to change and depolarize debate. For example:

- In debating a topic, research shows that using fewer arguments, and making them more effectively, is more persuasive. Piling on more but weaker points dilutes the power of the stronger ones rather than bolster them.

- Depolarize discussions by abandoning the binary “either-or” framing. Research shows that acknowledging uncertainty and complexity surrounding a topic makes writers and speakers more credible, not less.

- In team settings, create psychological safety, where mistakes are treated as learning opportunities, ideas flow freely, risk-taking is both possible and encouraged, and team members trust each other.

Think Again is full of great examples, ranging from the Yankees-Red Sox baseball rivalry to climate change. It is full of diagrams and illustrations, useful in understanding the many biases that lead us astray, including confirmation-, desirability-, status quo- and binary bias, as well as the Dunning-Kruger effect. (The Dunning-Kruger effect is overconfidence in estimating one’s ability; Grant’s much more descriptive term for the effect is the “Mountain of Stupid,” a point where people with less knowledge and expertise on a topic are more confident of their opinions than those with more knowledge and expertise).

Speaking of the Dunning-Kruger effect, I found myself lamenting the problem this book poses. Underlying Grant’s excellent analysis is a presumption that people have an intellectual dimension, an ability to “reason.” The book’s appeal is to break through barriers to truth by using reason and employing self-awareness, logic and prudence. However, the people who need this advice often do not believe in this type of process. They may view intellectual inquiry as either the enemy of good sense or beneath them: “Of course I’ll keep an open mind, but you’ll never convince me there’s a better way.”

Counterpoint: Sometimes We Are Not Wrong

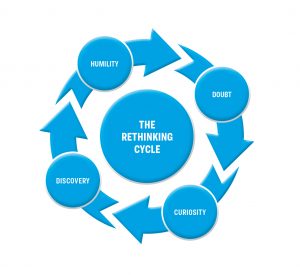

Herein lies one of the contradictions growing out of Grant’s proposition: being wrong is not always right. Grant offers the rethinking cycle as a virtuous loop, accepting that we may have been wrong, even embracing the venture into risk-taking, as a means leading to discovery — a good thing (See The Rethinking Cycle graphic below).

Sometimes, however, being wrong leads to grief. Once “making mistakes” is our method of discovery (i.e., “nothing ventured, nothing gained”), we lower our threshold to risk. The reality is that we are in a state of constant tension between seeking the benefits of accepting our wrongness versus doing our best to purge mistakes from our thoughts and our team dynamics.

Asymmetries of Risk: Thinking and rethinking must be calibrated to match the levels and types of risks faced. It is one thing for a hedge fund manager to be wrong about interest rates as they “discover” a winning formula to navigate financial markets. It is quite another for NASA engineers to test the limits of cold-weather conditions by proceeding with a rocket launch where O-rings may be compromised. The virtues of progress-through-discovery cannot be properly evaluated without a sober assessment of potentially ruinous consequences. Grant includes a discussion of NASA and the Challenger launch in his excellent section on psychological safety.

Sometimes we are not wrong: We are right, and the other person is wrong. Our present fractious political discourse is not lost on Grant. While he does not rush in on the most divisive issues, no doubt he hopes his methods can be used to heal our divisions. His analysis on the climate change debate is a good start on understanding his method without setting the book on a course that would alienate readers from either political camp. In addition, we are in a period of rethinking racism, white supremacy, and the institution and legacy of slavery: how do we deal with the errors of the past, when slavery was established and defended?

Conclusion

Not only does Grant provide many insights, but he has a sense of humor. In his own epilogue, he admits to hating conclusions. He writes, “If the topic is important enough to deserve an entire book, it shouldn’t end … I don’t want the conclusion to bring closure. I want my thinking to keep evolving.” He even provides his epilogue in edited format, showing the reader the development of his thinking to illustrate the nature of evolving thought.

He also quotes Governor Franklin Delano Roosevelt of New York, who later served as the president of the United States. As the state and the nation faced an unprecedented crisis from the depression, in 1932 he announced, “It is common sense to take a method and try it: If it fails, admit it frankly and try another. But above all, try something.”

Grant Concurs

“It’s easy to see the appeal of a confident leader who offers a clear vision, a strong plan, and a definitive forecast for the future. But in times of crisis as well as times of prosperity, what we need more is a leader who accepts uncertainty, acknowledges mistakes, learns from others and rethinks plans.”