Parts of the dairy supply chain showed resilience in the face of the pandemic’s epic disruption.

As the pandemic hit, shortages of many products left grocery shelves empty. Businesses such as restaurants and hotels shut down, while people panicked, hoarded and stayed at home cooking, causing a sudden shift in consumer behavior.

Meat, canned corn, Tostitos multigrain scoops, ketchup packets, caffeine-free coke and many other items were stocked out at the local grocery as the entire food supply chain shifted its manufacturing toward more popular, core products. Tony Vacchiano, who is an undergraduate student at Seton Hall University and works on his family farm, Vacchiano Farms, mentioned demand for meat at the local farmers market tripled as supermarket stock outs caused consumers to seek out other retail options.

The pandemic showed the need to respond rapidly to shifting demand. Increasing the ability to “see” what is happening throughout the supply chain to detect abnormalities, such as shortages and oversupply, would help to reduce waste, increase speed to market and increase margins.

The dairy industry was impacted harder and earlier than other agricultural products because of the highly perishable nature of the product. Images of farmers dumping milk, the main ingredient in the dairy food supply chain, while there were shortages at the local grocer created a strange dissonance.

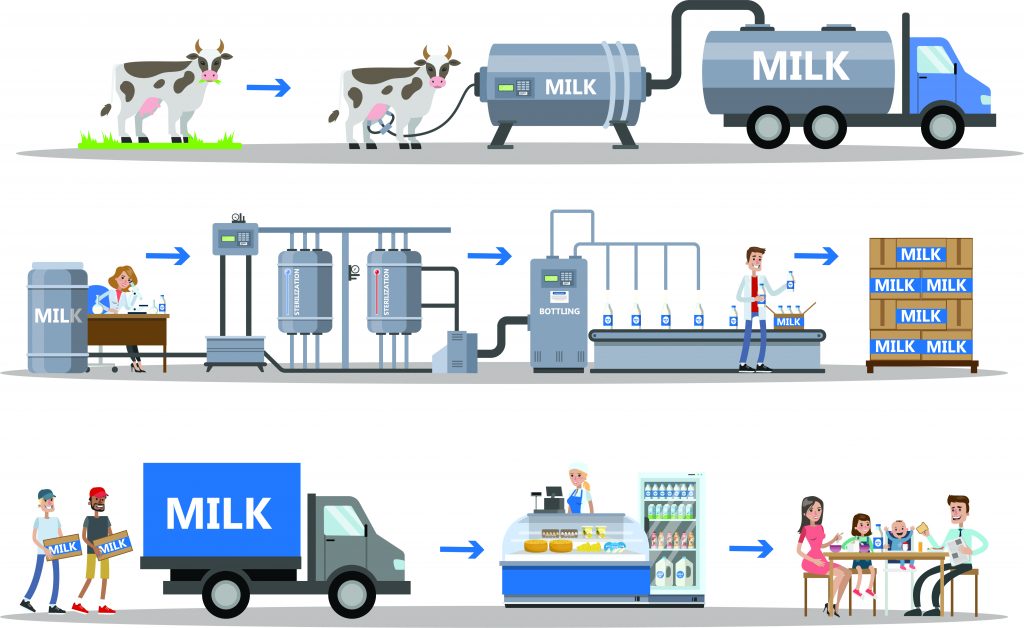

Figure 1 represents a typical dairy supply chain. The shift from wholesale food-service markets to retail grocery stores that occurred during the pandemic created packaging and logistical challenges for plants processing milk and milk products. These dairy products, packaged in large restaurant-size containers, could not quickly be repurposed for retail stores. Trucking companies were unable to get enough drivers due to the virus. Sales to major dairy export markets plunged because the global food-service sector had mostly collapsed. Despite it all, the dairy supply chain showed resilience, as farmers and processors were able to quickly cope with the situation.

As Jim Mulhern, chief executive officer of the National Milk Producers Federation, stated, “But the root of dairy’s resilience was centered, as always, on the farm … our farmer-leaders. Faced with an unprecedented rupture in the balance of supply and demand, many farmers used every tool in their arsenal to throttle back production — from changing feed rations and milking schedules to putting the brakes on herd expansion. Those efforts helped stave off what would have been a complete price collapse and they set the stage for a rebound.”

Co-ops Versus Proprietorships

The legal business structure provided closer relationships between the farmer and downstream manufacturers and distributors, enabling the dairy food supply chain to remain resilient. There are five major forms of business structures that farmers can choose: sole proprietorships, partnerships, limited liability companies (LLC), corporations and cooperatives. Each of these structures has advantages and disadvantages, but the one that seems to have been the most resilient during the time of the pandemic is the cooperative.

A cooperative is a “business owned and democratically controlled by the members who use its services and whose benefits are derived and distributed equitably on the basis of use.” Dairy cooperatives oversee milk marketing for all their members and handle shipping and logistics. Although farmers are paid for the milk they dump, the payments for all cooperative members took a hit from the lost revenues during the pandemic.

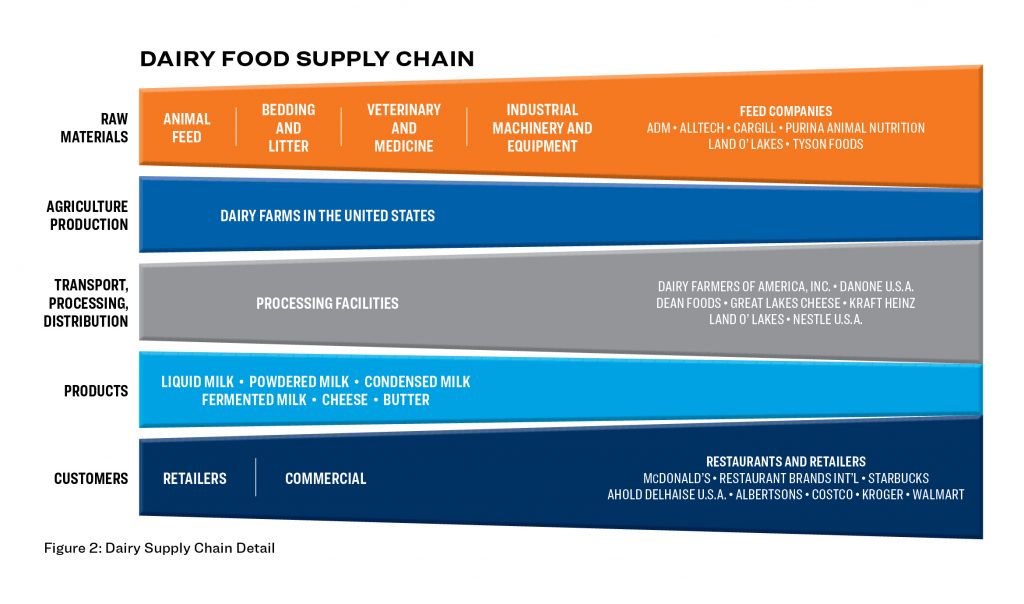

The sharing of financial benefits of a co-op creates a close union among its members. As seen in Figure 2, from the raw material vendors, farmers, transporters, processors and customers, each can partner or collaborate to form closer and mutually beneficial relationships. This would allow the supply chain to respond to demand changes more rapidly. Land O’Lakes, one of the largest agricultural co-ops in the nation, was able to adapt its dairy supply chain within a few weeks to handle the volatility of the pandemic because of such collaboration among its partners.

In Retrospect

While it is premature to look back while we are still in the throes of the pandemic in many parts of the world, some lessons are becoming increasingly apparent.

a. Human Intervention For many of the companies impacted during the pandemic, conventional planning solutions like ERPs and MRPs were of little use. Many of the forecasting capabilities in their demand planning module were based on historical data. With the pandemic, there is no precedent, and as Christian Edmiston, Director of Sourcing and Risk at Land O’Lakes, said, “We’ve shifted our efforts toward building in intentional flexibility to respond, rather than dwell on our inability to see what’s coming next.” The pandemic exposed the weaknesses of conventional planning solutions, pointing to the need for human intervention when the volatility of demand is much greater than normal. Therefore, systems should be used to augment our intuition of the decisions buyers/planners make. Systems should not dictate the running of our supply chains.

b. Flexible Supply Chains As demand from schools and restaurants ceased, co-ops fared better than independent farms. The former have established relationships from the farm to producer to the distributor, which enabled rapid change. In the case of Land O’Lakes, it was able to create new products, allowing it to store cheeses to last out the pandemic.

c. Demand Shaping Many companies eliminated low-margin or slow-selling products by focusing on fewer SKUs. This helped align the suppliers and buyers, and focused on the more important and higher-selling products, increasing profitability and ensuring supply in the groceries and supermarkets. This type of SKU rationalization is a form of demand shaping that gently pushes consumers toward available product. This can result in streamlining the supply chain, increasing profitability and also ensuring availability in the fewer SKUs.

Future Supply Chain Actions

As the dairy supply chain recovers, many companies, including Land O’Lakes, are looking to make changes in the handling of milk to adjust to an increasingly volatile world.

a. Demand and Supply Volatility There is renewed effort to find other ways to create more flexibility in the supply chain and minimize the reliance on forecasting, increasing the ability to respond to volatile changes in demand. Companies are looking at ways to increase resilience in the supply chain, which can be increasing inventories, adding capacity or utilizing secondary sources of supply.

b. Digitalization of Supply Chain to Increase Visibility The pandemic showed the need to respond rapidly to shifting demand. Increasing the ability to “see” what is happening throughout the supply chain to detect abnormalities, such as shortages and oversupply, would help to reduce waste, increase speed to market and increase margins. Digitizing strategic portions of the supply chain would be a future step to providing both the company with the ability to respond to changes and to deliver future reporting and traceability of product that the consumer may demand.

c. Risk Management Along with increased visibility, many companies are in the process of mapping key raw materials and suppliers, and developing mitigation steps to reduce risk. By mapping the supply chain, companies can strengthen areas of weaknesses and create a more resilient supply chain.

d. Ability to Use Data Increasing supply chain visibility will enable more data to be collected. The data could be sales information, financial data, transaction data from suppliers, transportation logistic data or point-of-sale data. Also, companies should increase use of external data sources, such as weather data, consumer preference data, Google trend data and, for food, online cookbook data. As these sources of data are collected, the need to process and create actionable insights becomes more important, and techniques like artificial intelligence, predictive algorithms and optimization will be deployed.

e. Management of Value Network Relationships One of the keys to success in the pandemic was the close relationship between the co-op members. Further development of these relationships and the ability to create flexibility in the supply chain will help ensure the industry can handle volatility caused by the pandemic or any future unforeseen event. As Christian Edmiston from Land O’Lakes said, “We have gone out of our way to give our strategic suppliers a chance to maintain business or even build business. When things get tight, those relationships have really shown value.”

Leadership Lessons

The pandemic highlights the need for strong leadership to manage through an abrupt change to the supply chain avoiding a price collapse of the dairy food products, as well as, positioning itself for recovery. In the case of Land O’Lakes, the speed to change the supply chain required decisive action and trust between the farmers, logistics providers, food processors and distributors. The production of milk flows continuously and it necessitates the coordination between all the players within the supply chain to act collaboratively.

This also shows the need for flexibility in the supply chain and the ability to adapt. As a leader, one cannot assume the future will be the same as the past. Decisions made in the past should allow for resilience and cooperation in the supply chain. The need to evaluate the current situation and have the right data at our fingertips is more important than ever to make informed and quick decisions that optimally enables each member of the supply chain network to coordinate its actions and come to an agreement.

Lastly, each company we spoke to showed care and concern over its employees. For those who could work remotely, they were given the ability to work from home. Those who needed to work on location, their workspaces were modified to limit the transmission of the virus, and safety precautions were put in place. So, empathy was shown to its internal supply chain, as well as to the external network thereby building trust.

As the world recovers from the pandemic, the dairy industry is evaluating what the future landscape will look like. But overall, the supply chain has been proven to be more resilient than expected.