There we sat around the large oak table with a bountiful feast in front of us. This year for Thanksgiving I traveled with my family to my Uncle’s house in northern New Hampshire. His “lodge,” as it is affectionally referred to, sits with a few other homes on a mountain that connects into a larger range of mountains and fields and lakes. With the inside nearly as beautiful as the outside, it was a wonderful time with great food.

Ironically, not on Thanksgiving itself but the following Friday after some guests had left, my family sat down to eat with my Uncle and his two young sons. Before eating, my Uncle had us join hands for a ‘family circle’ in which everyone expressed things for which they were thankful. His practice is emblematic of a very widely spread cultural practice of ‘giving thanks’ around this time of year. However, as I am confident many are also curious, to whom are we thankful?

In the 1600’s, the Pilgrims came, and gave thanks for a successful voyage. Of course, today, if all that is meant by “I am thankful” is I am glad about the outcomes of the random circumstances of life over which on a grand scale I have very little control, then I believe that is not a very sensible thing to do at all. Nor is it, in my experience what most people themselves believe they mean when they say, “I am thankful.” In fact, in our language and cultural celebrations we speak of giving thanks as taking time to express our gratitude over the good things we have received in the course of our lives.

However, if one follows the rather vacuous practices of our culture, they will find themselves in a rather perplexing circumstance. Why have we a desire to express something like gratitude, or how can we speak of ‘receiving’ if there is none towards whom we direct this gratitude or from whom we have received these good things? Of course, if one wishes to eliminate these considerations as vestiges from a more Christian past out of which Thanksgiving as a tradition grew but are now foreign to modern experience, one might speak of a general joy for the good experiences one has happened to have.

Yet, one is then left to consider what is meant by joy or indeed goodness. Are these merely subjective and different for each person? If so, then how can a common act of ‘giving thanks?’ exist. A rigorous defense of the Catholic theological and philosophical doctrines concerning these questions against objections is not the purpose of this article. Instead, the reader is encouraged to consider how they might approach these questions rather than accepting the ambiguities with which many are comfortable to cloak these practices.

Central to the Catholic faith is the dogma of the Holy Eucharist. Described by the Catechism of the Catholic Church, a concise summary of Catholic doctrine, as “the source and summit of the faith.” Its significance cannot be overstated. Used several times in the epistles of the Apostle Saint Paul, the word comes from Greek roots meaning, ‘thanksgiving.’

Understandably as the center piece of the Apostolic religion, the Eucharist is properly thought of as many things: sacrifice, spiritual food, and the cause of Catholic Christian community; but, it is also appropriately thought of as the means by which the Church, through the Lord Christ her Master, renders thanks onto God.

Certainly, this has clear parallels to our cultural holiday of Thanksgiving, and of course while we commemorate a Puritan celebration, there is a Catholic history to Thanksgiving in the United States as well.

Squanto, the famed Native who helped the Puritan settlers survive the harsh winter had many years before been freed from slavery by Spanish Jesuit priests. After being captured by English settlers lead by Thomas Hunt, Squanto was made a slave and brought to Europe.

At the time, Pope Paul III had recently promulgated the papal bull “Sublimus Dei,” which forbade the enslavement of Natives in Catholic countries. As such, the priests purchased Squanto and set him free. He was taught the Christian doctrine by these men and was likely baptized a Catholic before the priests helped connect him with a man who paid for his return to the United States. However, even before the famed Plymouth Rock Thanksgiving, there were several Catholic celebrations in the New World.

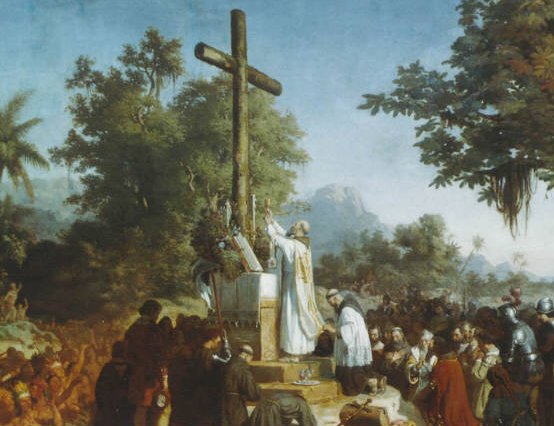

On September 8, 1565, many years before the landing in Plymouth Rock, Spanish settlers lead by Don Pedro Menendez landed in St Augustine Florida. Tradition holds that when Menendez came ashore, he instructed the head chaplain of the voyage, Father Francisco Lopez de Mendoza Grajales to lead a chanting of the “Te Deum.” Father Lopez de Mendoza Grajales presented Don Menendez a crucifix which Menendez then kissed. Afterwards, the entire party of several hundred joined the Timucuan Natives in the offering of a Mass in thanksgiving of a safe voyage and a large feast with the local tribe.

As University of Florida professor Michael Gannon noted in his work, “The Cross in the Sand,” “It was the first community act of religion and thanksgiving in the first permanent settlement in the land.” Integral to their convictions was this act of giving thanks, and this practice is clearly not something our culture, despite its vast differences has really moved away from.

Later, On April 30th, 1598, Spanish explorer Don Juan de Onate also completed a successful voyage from Spain to the Americans. Amidst a chorus of trumpets and cheers for a successful voyage de Onate signed and sealed the official act of settlement with the Holy Cross. He then had his friars offer a Mass of Thanksgiving. Following this, the whole company enjoyed a feast of duck, geese, and fish. The meal was accompanied by plays, which depicted some of the early Franciscan martyrs in the New World along with scenes of early Native converts. Certainly, these men had no confusion as to Whom they gave thanks.

For them, giving thanks was a sensible act which they as creatures offered to their Creator for as His gifts. I resound their response that I am thankful to Jesus Christ. I am thankful to Him for my life, my family and friends, my time at Seton Hall whereby I can learn more about the world and enjoy the fruits of learning the truth. I am thankful to Him for His priests, especially those at Seton Hall, the priests who make our Lord present to us by the Most Blessed Sacrament, who teach us His doctrines, and who make His love present to us through their own love, as teachers, counselors, and mentors. As we end this period during which the culture pays considerable attention to giving thanks, consider what you yourself mean by giving thanks and to whom you offer it.

1- Jesuit Missionaries to North America:

Spiritual Writings and Biographical Sketches by Francois Roustang

2- https://taylormarshall.com/2013/11/6-interesting-catholic-thanksgiving.html

3- The Cross in the Sand by Michael Gannon

4- Don Juan de Oñate and the First Thanksgiving by Don Adams and Teresa A Kendrick