“War causes enormous numbers of specific injuries and conditions. Often special hospitals had to be set up to deal with them. In 1916, during the First World War, Craiglockhart War Hospital for Officers near Edinburgh was set up to deal with shell-shocked officers. Originally the buildings were part of a hydropathic institute, where patients went to receive water therapy. Sporting facilities included swimming, golf, tennis and cricket. Patients made model yachts, joined the camera club and walked in the fields around the hospital.

The patients would be occupied during the day, but often wandered the corridors at night. Many of them were haunted by the horrible scenes of death and destruction that they had experienced. Craiglockhart’s most famous patients were the war poets Siegfried Sassoon and Wilfred Owen. They were treated by William Rivers, the famous psychologist who developed the ‘talking cure’ for shell-shocked officers at Craiglockhart. It is now part of Napier University” (Science Museum).

It is important to note what the different things this hospital did in comparison to other hospitals during that time. There were a primary two methods used by the two different doctors that had treated Siegfried Sassoon and Wilfred Owen, respectively. A variety of treatments were used at Craiglockhart. William Rivers drew on ideas from psychoanalysis and helped popularise Sigmund Freud’s work with his use of the ‘talking cure’. But Arthur Brock thought the key was to keep the patients active (Theatre Cloud).

Elaine Showalter wrote of the various things done to soldiers in irder to cure them during this time. She writes of the treatment that Sassoon received, even though he wasn’t actually neurasthenic, placed in the hospital only on the basis of his friend Robert Graves who was trying to protect him.

“In this case the diagnosis was neurasthenia, the setting was Craiglockhart Military Hospital near Edinburgh, the therapist was Dr. W. H. R. Rivers, and the patient was Second Lieutenant Siegfried Sassoon. This time the patient and the doctor were friends; the therapy was kindly and gentle; the hospital was luxurious; the most advanced Freudian ideas came into play. Yet the reprogramming of the patient’s consciousness was more profound and longer-lasting than in Yealland’s electrical laboratory” (Showalter).

So as one can see, there were indeed various methods that seemed to work, yet some seemed better or longer lasting than others. Another method Showalter wrote about was in the difference between how men and women were treated.

“The contrast to both the treatment of hysterical soldiers and the rest cure of neurasthenic women is significant. Many military psychiatrists had criticized the usefulness of Weir Mitchell’s rest cure for shell-shock patients. Soldiers who were isolated and treated with the rest cure, R. D. Gillespie claimed, did not recover and remained ill throughout the war. Hugh Crichton-Miller protested that rest in bed, nourishment, and encouragement were insufficient to restore masculine self-esteem: ‘Progressive daily achievement is the only way whereby manhood and self-respect can be regained.’ Thus instead of the enforced passivity of Virginia Woolf or Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Sassoon was encouraged to resume a life of energetic masculine activity. He was provided with a room of his own, and a place to publish his work. As a poet, he was never deprived of his voice” (Showalter).

Both Sassoon and Owen were at the hospital in 1917, where Sassoon encouraged Owen to write his poetry. The pair were seen by many to have a romantic relationship though a big part was their influence on one another in terms of their literary work.

Finally, there is information as to the work both poets did while at Craiglockhart. The hospital was not just a hospital, it was a meeting place for these great poets. Without this meeting, readers today would not have even heard of Owen’s work as he was primarily unpublished besides his work in the literary magazine of the hospital itself. Their influence on each other remains a great factor today as evidenced through their work as two of the greatest war poets.

Siegfried Sassoon

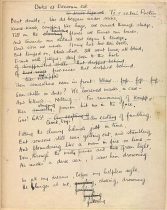

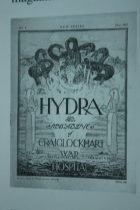

“In 1917 Sassoon wrote a statement condemning the war which was read out in parliament by an MP. To avoid a court martial, his friend and fellow writer Robert Graves convinced the review board that Sassoon was suffering from shell shock. He was sent to Craiglockhart to recover. Sassoon had been a published writer before the war and he continued to write while at Craiglockhart. The poem Dreamers was first published in The Hydra. He eventually returned to the front in France before a head wound led to him being invalided back to Britain, where he spent the rest of the war” (Hammond).

Wilfred Owen

“Owen saw fierce fighting during the war, including being trapped for days next to the dead body of a fellow officer. Such events severely traumatised him and he became a patient at Craiglockhart. His doctor, Arthur Brock, encouraged him to write as part of his treatment and he was for a time editor of the Hydra. He was also inspired by meeting the older Sassoon, who would offer feedback on his work. Owen’s best remembered poems, such as Dulce et Decorum est and Anthem for Doomed Youth, were written at Craiglockhart. Like Sassoon, Owen returned to the front in France after leaving Craiglockhart. He was killed on the 4th of November 1918, one week before the Armistice was declared” (Hammond).

Works Cited