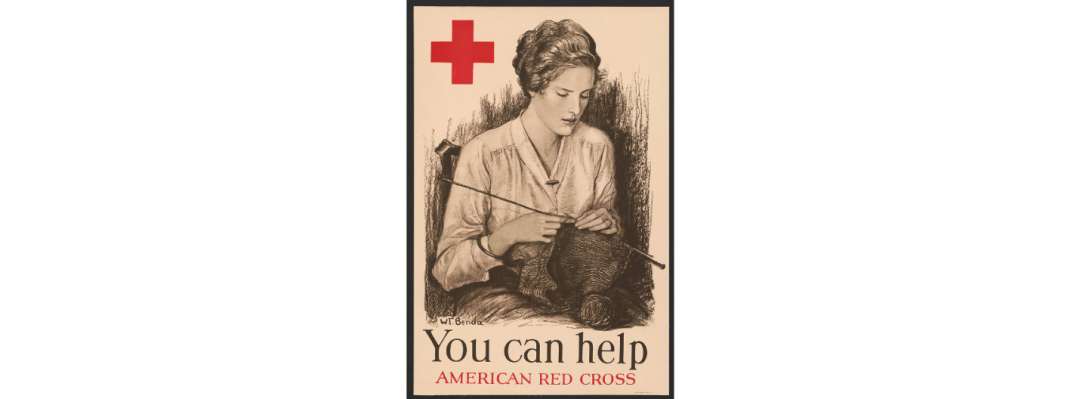

The source listed above is a propaganda poster developed in 1918 during the First World War by W. T. Benda. Pictured is a young woman seen knitting with the words “You can help; American Red Cross.”[1] During the First World War, propaganda posters were very common; in fact, propaganda took many forms including newspapers, radios, speeches, films, and campaigns.[2] The reason behind the increase in propaganda was to gain support of the American citizens for the First World War.[3] This specific propaganda poster was designed to reach the audience of women to help aid soldiers in any way they could, whether it be by volunteering to be a nurse, making clothes for the soldiers, or giving support to their families and loved ones. Some women who volunteered as nurses helped specifically aid soldiers’ physical wounds they would experience during battle. Some of these nurses dedicated their lives to helping soldiers and travelled to various locations in an attempt to contribute everything they could.[4] Women played a huge role in not only this war, but every other war as well. Not only did they commit themselves to volunteering to help the soldiers, but they also took over the jobs that the men had to abandon to go fight in the war.[5]

It is common to immediately think of nurses as those who helped with soldiers’ physical ailments; however, the rise of “shell shock” and “war neuroses” led to the dire need of psychiatric care to these soldiers, which was granted through the first psychiatric facility to be opened for a war.[6] Therefore, relevant to the poster, volunteers in both medical fields and psychiatric fields were encouraged, as these women were crucial to the health of wounded soldiers in the war.

The goal of this poster was to influence all women to help in any way they could. The poster shows a woman knitting, but has a message of the American Red Cross which is relevant to nursing. The significance of this relates to the idea that the message “You can help”[7] is not isolated to medical care or providing clothes and materials; it also means contributing to the community who were indirectly impacted by the war. In other words, if one was unable to provide medical assistance, they could help in other ways too. For example, there were some programs instituted that were meant to teach women domestic skills relating to nutrition and cooking in order to help rebuild the health of those experiencing poverty.[8] Contributions relating to this nature are just as significant as providing aid to those who were affected firsthand by the war. Therefore, the message “You can help”[9] truly extended beyond just providing medical assistance, but other forms of assistance as well, hence the woman knitting within the American Red Cross poster.

The use of propaganda posters related to gaining needed attention and support. Many Americans were against the United States entering the war, which is why so many Americans were in support of reelecting President Woodrow Wilson as he successfully remained neutral for most of the war.[10] Many prominent figures in America, like Theodore Roosevelt, assumed America would eventually enter the war, which led to the initiation of the preparedness movement which supported strengthening the military by increasing spending for weapons and expansion.[11] This caused distress among Americans, as they felt this was just a means for financial gain for big businesses and a feeling of betrayal that President Wilson was secretly plotting to enter the war.[12] Although President Wilson reassured the citizens that they were not in a hurry to enter the war, ultimately, it was inevitable.[13] Propaganda was evident throughout the entirety of World War I, but when it came time for America’s entrance, propaganda posters increased as President Wilson knew he needed the support of the citizens to ensure a swift war would occur.[14] Therefore, propaganda posters similar the one listed above, were used to encourage citizens to help any way they could, as their contributions were vital to the success of the United States in the war.

[1] The Library of Congress. “You Can Help–American Red Cross / W. T. Benda.,” n.d. https://www.loc.gov/resource/ppmsca.40832/.

[2] David E. Shi. America: A Narrative History (Brief Twelfth Edition) (Volume 2). 12th ed. W.W. Norton and Company, 2022., 898-899

[3] Ibid

[4] Michelle, Moravec. 2016. ““Till I have done all that I can”: An Auxiliary Nurse’s Memories of World War I.” Historical Reflections 42 (3) (12): 71-90. doi:https://doi.org/10.3167/hrrh.2016.420305. https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/till-i-have-done-all-that-can/docview/2678547107/se-2.

[5] Shi, America: A Narrative History (Brief Twelfth Edition) (Volume 2), 898-899

[6] Carolyn, Castelli. 2021. ““Missing in Action” in Psychiatric Nursing History: The Role of Chief Nurse Adele S. Poston and Her Band of Nurses during World War I.” Journal of Psychosocial Nursing & Mental Health Services 59 (6) (06): 37-47. doi:https://doi.org/10.3928/02793695-20210219-02.

[7] The Library of Congress. “You Can Help–American Red Cross / W. T. Benda.,” n.d. https://www.loc.gov/resource/ppmsca.40832/.

[8] Carol L. White. 2019. “Knitting and Cooking for the War: Home Economics and the Poetry of the First World War.” Americana : The Journal of American Popular Culture, 1900 to Present 18 (1) (Spring). https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/knitting-cooking-war-home-economics-poetry-first/docview/2331693824/se-2.

[9] The Library of Congress. “You Can Help–American Red Cross / W. T. Benda.,” n.d. https://www.loc.gov/resource/ppmsca.40832/.

[10] Shi, America: A Narrative History (Brief Twelfth Edition) (Volume 2), 891-897

[11] Ibid

[12] Ibid

[13] Ibid

[14] Ibid