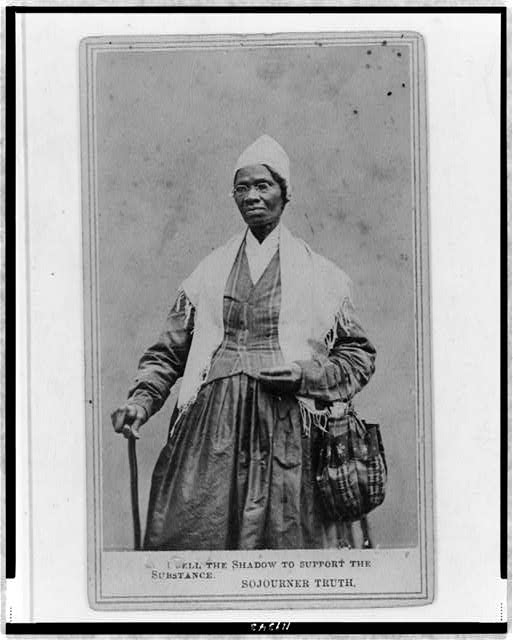

The photo of Sojourner Truth titled, I Sell the Shadow to Support the Substance, was her way of taking control of society’s view of her as a black woman. This photo is a carte de visite, or calling card, which is a small card that people used to carry around during the 18th and 19th centuries to call on others. They were used as a form of formal communication to send messages, announce one’s arrival at their home, or schedule meetings. Truth utilized the invention of calling cards to not only control the way she is portrayed, but to also help her financially. During the mid to late 1800s, Truth was well-known for her work advocating for women’s rights and emancipation. She needed a means to continue her work and travel to places throughout America, so she began taking professional portraits of herself, copyrighting them, and selling them at her own lectures. Truth made it known that by doing this, she is selling herself on her own terms not on the terms of anyone else, hence the title. The “shadow” is herself in the photograph in the exact way she chooses to portray herself and the “substance” is her activism in support of Black people. 1

Before Sojourner Truth, there was Isabella Baumfree. Isabella Baumfree was born into slavery in 1797 in Ulster County, New York. In 1826, Isabella freed herself from her slave owner and ran away with her infant daughter. She gained refuge with a kind Dutch family that freed her from the treacheries of slavery. 2 Out of gratitude, Isabella adopted their last name, Van Wagenen, and began her religious journey within their home. Isabella soon learned that her previous slave owner sold her young son. Obviously enraged, Isabella went forth to take her son back which she did with great success. The years after she freed herself were extremely critical regarding her future activism. The exposure to religion in the Van Wagenen household and the legal fight she had to endure to get her son back was the stepping stone to ignite her activism.

Her fiery activism drew her to evangelical reform groups in New York City where she was encouraged to preach in places no white male preachers dared to go. In the article, Going “Where They Dare Not Follow”: Race, Religion, and Sojourner Truth’s Early Interracial Reform, Isabella was sent to preach in areas like black working-class neighborhoods, brothels, and alleys. By Isabella preaching to those in worse conditions compared to the usual middle-class people she would preach to, she provided those in more difficult positions hope and encouragement. Though some of her own people still preferred preaching from white women, she was not discouraged. She continued speaking her truth to all who were willing to hear her and eventually renamed herself as Sojourner Truth. Around the time this photograph was taken, the Civil War ended and slavery along with it. However, there was still much work to be done regarding emancipation, women’s rights, and citizenship. With that in mind, Truth continued her fight to ensure everyone got what was rightfully theirs.3

Every little detail present in Truth’s photographs was intentional. From her posture, to her outfit, to her facial expression, everything was calculated. It had to be because she was well aware that anything she did as a black woman would be dissected under a microscope. As Zackodnik explains, Truth’s work was often “double-voiced” because she had to deal with “conflicting demands” of both her black and white, female and male audiences.4 Truth had to be very cautious in the way she portrayed herself– not because she truly cared for their approval, but because gaining their support would bring her one step closer to her goal. In the photograph, she is wearing a simple dress, a white shawl and bonnet, and glasses. She is holding a cane and a plaid bag with a straight, composed expression. Every aspect of this photo portrays her as civil, well-kept, and upright. It completely opposes the usual racist caricatures of Black women created by white artists with the intention to demean them and portray them as wild and indecent. These photographs were made strategically to force society to see Black women in the proper light.5

Citations

Margaret Washington. “GOING ‘WHERE THEY DARE NOT FOLLOW’: RACE, RELIGION, AND SOJOURNER TRUTH’S EARLY INTERRACIAL REFORM.” The Journal of African American History 98, no. 1 (2013): 48–71. https://doi.org/10.5323/jafriamerhist.98.1.0048.

Zackodnik, Teresa. “The ‘Green-Backs of Civilization’: Sojourner Truth and Portrait Photography.” American Studies 46, no. 2 (2005): 117–43. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40643851.

Zackodnik, Teresa C. “‘I Don’t Know How You Will Feel When I Get through’: Racial Difference, Woman’s Rights, and Sojourner Truth.” Feminist Studies 30, no. 1 (2004): 49–73. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3178558.

Image Source:

https://www.loc.gov/resource/cph.3c19343/