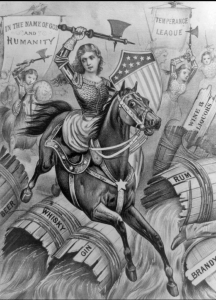

Currier & Ives: Woman’s Holy War Woman’s Holy War

The Temperance Movement was something that affected Americans for many decades. The biggest supporter of this movement were women. Women witnessed firsthand the effects that alcohol had on their families, and it caused a lot of pain and trauma to them. This image “Woman’s Holy War”[1] was created by Currier & Ives in 1874, which is a vivid example of the moral conflict and the organized activism that brought women together so that they could fight the greater evil. The movement of abstaining from alcohol started in the early 19th century by religious groups, which included groups like the Methodists.[2] These religious groups were afraid of alcohol’s effect on humans, like reasoning and behavior. The movement somewhat faded during the Civil War but later resurfaced during the industrialization era.[3] Those in support of the temperance movement believed that this was a very important social issue that needed to be fixed.

The abolition of alcohol and of the liquor trade was important to public health and social justice that was often compared to the abolition of slavery by the supporters, that this cause was a greater good that will benefit. Advocates referred to alcohol as “new and more dangerous form of slavery”[4] and believed that alcohol abuse “destroys the sense of decency and honor, silences conscience and deadens the best instincts of the human heart.”[5] After witnessing the horrors that affected their families, women got together and founded the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union in 1873. These women were seen by those around them as “petticoated Christian soldiers”[6] since these women would routinely storm saloons and would recite the Bible. These women would lay their Bibles on the bar, pray aloud, and would plead with the barkeepers to stop sales, and would sometimes cause the flow of liquor to be closed. The image name of the “Woman’s Holy War”[7] shows how the women who fought for this cause saw themselves as an army who were fighting to protect their families and homes. Women leading this reform were seen as suspicious by those around them, since society believe that they were not acting appropriate when it came to their gender roles, as they should be focused on running their homes and raising their families. However, these women were doing just that, they were fighting to improve their home life and protect their family, this is what this movement believed in. This is backed up by the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union; they argued that women must intervene publicly because it is their duty to protect their family from the dangers of alcohol. The goal for most WCTU members was to completely abolish alcohol, as they saw moderation as a dangerous trap that will lead to abuse at the end. This image was meant to persuade others to join the moral fight and to show that women could be successful with their goal, they were fighting to save their families. This image showed that women were wielding “powerful weapons that could be used to save drinkers.”[8] The women were depicted as soldiers in this image, which is very different than the appropriate gender norms of the 19th century. Women often used songs and prayers to persuade people towards abstinence, they wanted others to join their cause and to eventually create structural change. “Woman’s Holy War”[9] shows us that this period was defined by the need of national moral reform efforts by women. It marks when women created a public space where they could freely speak and fight for what they believed.

[1] Currier & Ives. 1874. Woman’s Holy War. https://www.britannica.com/topic/temperance-movement.

[2] Webb, Holland. “Temperance Movements and Prohibition.” International Social Science

Review 74, no. 1/2 (January 1, 1999): 61

[3] Murdach, Allison D. “The Temperance Movement and Social Work.” Social Work 54, no. 1

(January 1, 2009): 56–62. https://research.ebsco.com/linkprocessor/plink?id=7cf7c47b-01ee-

3612-a277-d26c455930fb.

[4] Murdach, Allison D. “The Temperance Movement and Social Work.” Social Work 54, no. 1

(January 1, 2009): 56–62. https://research.ebsco.com/linkprocessor/plink?id=7cf7c47b-01ee-

3612-a277-d26c455930fb.

[5] Webb, Holland. “Temperance Movements and Prohibition.” International Social Science

Review 74, no. 1/2 (January 1, 1999): 61

[6] Beard, Deanna M. Toten. “‘The Power of Woman’s Influence.’” Theatre History Studies 26

(June 1, 2006): 52–70. https://research.ebsco.com/linkprocessor/plink?id=291f1c28-0e2e-314f-

b40e-0ac57c7fa43c.

[7] Currier & Ives. 1874. Woman’s Holy War. https://www.britannica.com/topic/temperance-movement.

[8] Murdach, Allison D. “The Temperance Movement and Social Work.” Social Work 54, no. 1

(January 1, 2009): 56–62. https://research.ebsco.com/linkprocessor/plink?id=7cf7c47b-01ee-

3612-a277-d26c455930fb.

[9] Currier & Ives. 1874. Woman’s Holy War. https://www.britannica.com/topic/temperance-movement.