Before the war, Simeon Moss was playing for Rutgers University’s sprint football team. Less than a year later, he was drafted as a private into the United States Army and quickly climbed the ranks to become a second lieutenant infantry officer.

On Dec. 7 of last year, the New Jersey native was living in Chicago as a teacher. It had been less than six months since he graduated as the only black student in his senior class.

“On the day Pearl Harbor was bombed, I was at the football game and they announced it… I went right back home and wrote ‘em a letter and told ‘em to draft me. About a month later I got the letter, transferring me to the headquarters and I was drafted from Chicago.”

Although eager to be a part of the armed services, Moss hasn’t always had the best relationship with the military. While in college, Moss was required to take two years of the Army Reserve Officers’ Training Corps (ROTC). He wasn’t a fan of it.

“I fought the whole thing,” he said of his experience with the officer training program. “If they said, ‘Column left,’ I turned right.” After Pearl Harbor, however, he had a change of heart.

“I’m in this Army now, I’m gonna try to make as much out of it as I can,” he said.

Truth be told, Moss said that up until December 1941, he–along with most of the Rutgers student body–had not really been concerned with what was going on in Europe.

“I think that we were mildly aware, but not heavily aware,” Moss admitted. “I don’t think the real awareness came until just before Pearl Harbor… when [the United States] changed their concentration from the eastern powers to Japan… That’s when the newspapers got it and most of us only read the front page anyway.”

Moss was inducted last spring when Chicago was still as cold as the deep winter. There was even snow on the ground when he was sent to the Fort Custer Training Center near Battle Creek, Michigan to earn his commission. He and his engineering outfit went on Army maneuvers to build bridges across the river.

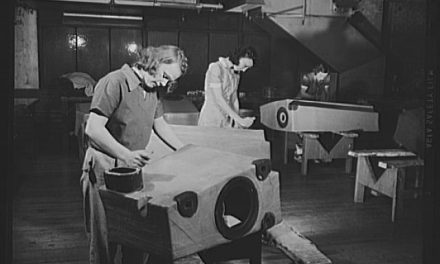

Armored forces in Fort Benning, Georgia, where Simeon Moss trained. Photograph by Alfred T. Palmer (Library of Congress).

After his stint in Fort Custer, he was transferred again with a number of fellows to Camp Edwards in Massachusetts.

Because of his experience in ROTC, Moss already knew a great deal about close order drill, so he was picked to be one of the acting sergeants. He then took the test to go to Officer Candidate School (OCS) and landed himself a few miles from the camp in Cape Cod.

“I was just beginning to enjoy it with all the women around and everything,” he joked about his short stay in Cape Cod prior to his transfer to Fort Benning, Georgia. Within a year, Moss has traveled across the northern United States, more than he ever did growing up.

Although he was born and raised in New Jersey, his parents were childhood sweethearts and originally from Georgia. His mother is a college graduate with a teaching degree and his father owned a bake shop in Augusta. Before Moss and his two sisters and brother were born, his parents settled in a fully integrated Princeton neighborhood. Finances were always tight throughout the economic depression of the 1930s.

“I once broke a man’s window,” Moss said of a childhood mishap that occurred while he was playing football. After the accident, he had to beg his father for fifteen cents and wait two days to get the money, because his father didn’t have it at the time.

In spite of his hardships, Moss got involved in extracurricular activities like soccer, football, softball, and worked odd jobs on his summers off from school.

Unlike his childhood and college experience, the 385th Engineer Battalion in which Moss serves is lawfully segregated. Throughout his primary and secondary education, the schools in his neighborhood were separated racially but it was not a result of any segregation laws. With everyday activities such as working or even going to the movies, there was no imposed ethnic separation in his neighborhood. Higher-ranking officers of his battalions are exclusively white. According to Moss, however, other white infantries within his battalion regularly congregate with the black infantries.

“The guys mingle,” Moss said of the relationships between the soldiers in the barracks. There was an instance when a white child visiting Fort Benning with his parents directed a racial slur at Moss, but he said that other than that, he has not personally experienced any blatant disrespect from white soldiers. “I never [see] any real tension that promotes flashes of anger, or fighting or anything like that. I’ve never heard one time of anybody pulling out a gun and shooting someone else, when it [can be] done in some of the situations we [are] in.”

Moss says that the hardest part about being an infantry officer is organization and making his unit a fighting unit. None of them have had much experience with war and combat. It’s an experience Moss has never imagined himself being a part of.

“It’s hard when you’re out here with the unit and you don’t know the nature of your enemy. They come from all angles and [I] really have to do a lot of teaching… Everybody’s got to know what they’re supposed to do at a certain time. And it takes a lot of training,” Moss said. He went on to say that people who aren’t well-versed in war zone tactics think that attacking their targets is simple. “It’s not that way. It scares you to death. I [hear] shells go over my head, and I [think] for sure they are coming down at me.

“[One] night we were, maybe a hundred yards from [the enemy] … We were giving ‘em fire instructions, and the [enemies] fired [a bomb] almost in the middle of our unit. That scared me to death. I didn’t know what to do: tell [his infantry] to stop firing, to raise it fifty feet, or what. It’s just one of these things.”

Source:

Moss, Simeon Oral History Interview, May 2, 1997, by G. Kurt Piehler and Sandra Stewart Holyoak and Melanie Cooper, Rutgers Oral History Archives. Online: http://oralhistory.rutgers.edu/social-and-cultural-history/31-interviewees/1133-moss-simeon (Last Accessed: March 26, 2017)